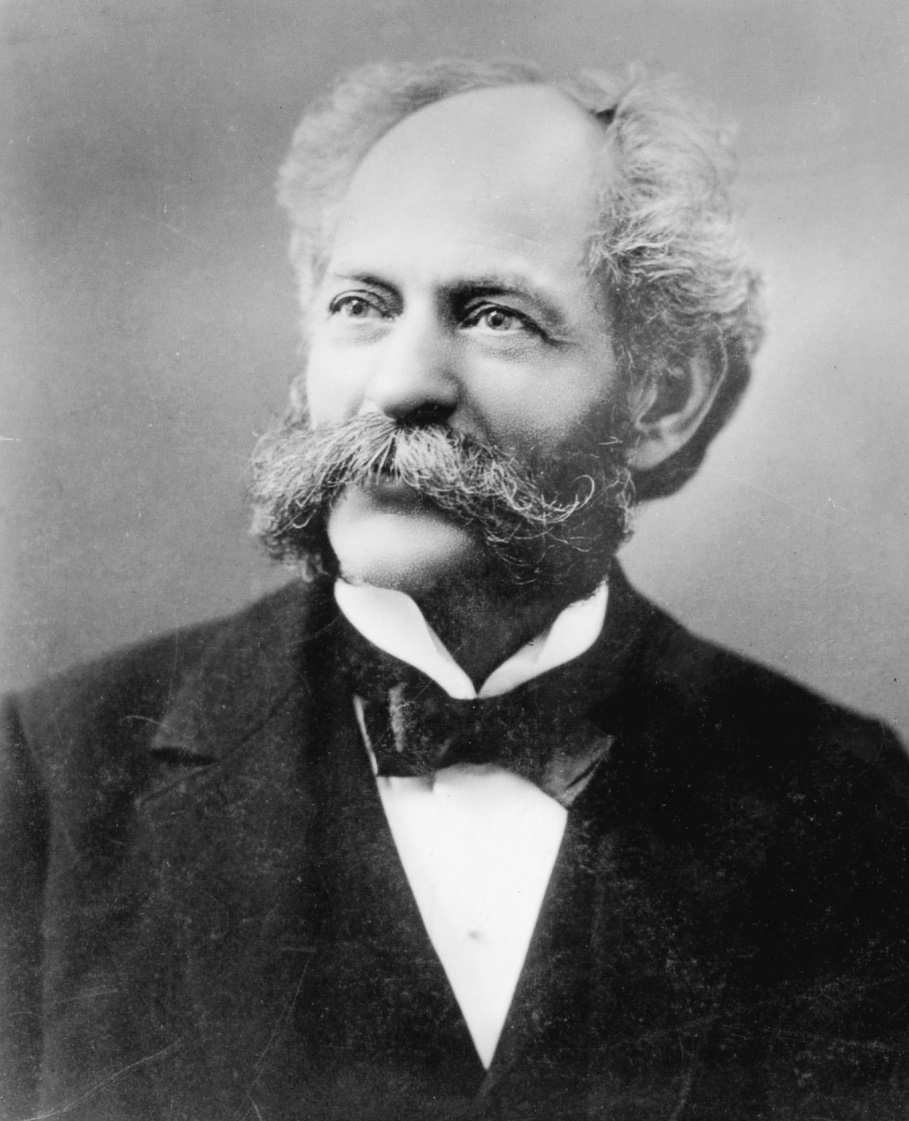

It’s December 1875. Thirty-one-year-old Henry John “HJ” Heinz is bedridden the entire month with deep depression. On some days, he cannot even get out of bed. His world has collapsed around him. For the last six years, he and his friends and financial backers, the Noble Brothers, have built their Heinz, Noble, and Company into one of the leading Pittsburgh suppliers of horseradish, vegetables, and condiments. They have created a strong brand and expanded to St. Louis and Chicago.

But now the “Panic” (depression) of 1873 has reached Pittsburgh. The skies are clear of the smoke produced by the iron and steel works and glass factories as they sit idle and thousands are thrown out of work. Heinz, Noble had contracted for the entire output of a cucumber farm in Illinois, but now prices are dropping and unneeded, expensive cucumbers are flowing into Pittsburgh.

Struggling to pay the bills, HJ Heinz has borrowed every cent available. His home, furnishings, and his father’s longstanding brickyard are mortgaged to the hilt. Falsely accused of moving inventory out of the reach of creditors, Heinz was even arrested, making news in the local papers. Bankruptcy, the ultimate disgrace to a traditional German Lutheran family like the Heinz family, was unavoidable. His friend Clarence Noble, after whom HJ had named his firstborn son, blamed HJ for their difficulties and turned his back on him. HJ’s younger brother, Peter, who worked as a salesman for the company, turned to drink, to which the teetotalling HJ was strongly opposed. HJ’s wife, Sarah, lost ten pounds from sheer worry.

As you might have guessed, HJ Heinz did in fact recover from the failure of Heinz, Noble, and by the spring of 1876, he was back in business. Heinz went on to lead the nation (and often the world) in his business practices, in many aspects predating other innovators by decades. Here is the story of this remarkable man, starting from his beginnings.

“To do a common thing uncommonly well brings success.”

The Foundations

The 1840s saw a large wave of German immigrants come to the United States. Wars, economic downturns, and religious struggles led these people to seek greener pastures on the other side of the Atlantic. America was promoted as a place with plenty of work, cheap fertile land, and a low cost of living. HJ’s father, John Henry Heinz, emigrated from Bavaria in Germany to the south side of Pittsburgh at the age of twenty-nine in 1840. His mother, Anna Schmidt, made the same trip with her family three years later, when she was twenty-one. That same year, 1843, John Henry and Anna met and were married, and the first of eight children, Henry John Heinz, came along on October 11, 1844.

These hardy German Lutherans brought many skills and attitudes with them. They knew building and brickmaking, carpentry, and above all, farming; they were hardworking and devoutly religious with high ethical standards. Nevertheless, they were near the bottom of the social ladder in Scotch-Irish-dominated Pittsburgh, which was emerging as the transportation and manufacturing hub of the nation and the largest city west of the Alleghenies. Its main industries included pig iron, glassmaking, brickmaking, cotton mills, and breweries. Three great rivers linked Pittsburgh to the expanding interior, including St. Louis and New Orleans. By the 1850s, a spider-web of railroads would extend from the city in all four directions.

HJ’s father, John Henry, worked for other brickmakers for a while before starting his own brickyard in 1850. The local riverbanks held the ideal clays and shales for making bricks for a variety of uses. John Henry moved the family five miles up the Allegheny River to the small town of Sharpsburg to be close to these resources.

Like other German families, the Heinz family had a garden of several acres to grow their own vegetables, including cauliflower, carrots, potatoes, cabbage, and horseradish (a German favorite). Tomatoes were added later as they grew in popularity. Along with his younger siblings, young HJ worked long hours tending this garden. By the age of nine, he was selling the surplus harvest of the garden to other Sharpsburg families. Showing an entrepreneurial bent, by age ten his parents gave him his own three-quarter of an acre to use as he pleased.

At twelve he had his own three and a half acres, and soon replaced his wheelbarrow with a horse and cart to make larger deliveries and sell more product. He also began a lifetime of experimentation with different crops and seeds, discovering what worked best and recording every experiment. He studied his mother’s recipes from the old country. And he was obsessed with studying his customers, learning what they wanted and preferred. Throughout his life, he kept voluminous notebooks on his observations of farm production, processing methods, and most of all, customer preferences.

But working on the farm and selling produce was not enough to consume HJ’s energies, as by age ten he was doing other odd jobs for neighbors, working in his father’s brickyard, and leading canal boats down the nearby canal as a “towpath boy.” He learned the importance of transportation networks, an interest that was to serve him well later in life. In the brickyard, he learned the importance of chemistry and temperature control, how to handle bulk materials, and the critical nature of the quality and quantity of ingredients. In later years, he carried a tape measure everywhere he went, keeping measurements of whatever interesting things he saw.

In these early years, his mother instilled in him strong religious beliefs—he turned out to be a Sunday School teacher his entire life. He went on to be an important proponent of the Sunday School movement all over the world, always observing different methods and always learning, taking notes. He evolved from a Lutheran to a Methodist, but was open to all faiths. Anna Schmidt Heinz filled the family with sayings and proverbs such as, “Always remember to place yourself in the other person’s shoes.”

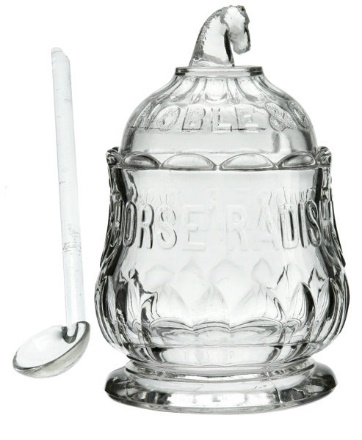

By the time he was fifteen, it was clear that of all his jobs, producing and selling garden produce was his real passion. Horseradish was his first focus. Homemakers in those days made their own horseradish by grating the plant. This took time, bruising knuckles and watering eyes. Heinz’s bottled horseradish was an early “convenience food,” saving time and energy. HJ found that by using more expensive clear glass bottles, his customers could be assured of the product’s purity. Using rarer clear vinegar instead of brown apple cider vinegar showed the horseradish to its best advantage. Soon HJ was traveling to Pittsburgh to personally sell this and other premade products to hotels, restaurants, and wholesale and retail grocers. Everywhere he traveled, he took notes on the market, the competition, and what customers wanted.

These early lessons led HJ Heinz to believe in several key principles. First was the importance of purity and quality of product, in an era when others used sawdust and floor scrapings as filler in their products. Second was the necessity of using only the best raw vegetables to insure his high quality standards, and to continually experiment with new seeds and plants. Third, he understood the importance of packaging—that a better package could increase sales and often allow higher pricing. Other lessons were to follow as HJ pursued his ambitions.

HJ also attended Duff’s Mercantile College in Pittsburgh, where he learned double-entry bookkeeping, which he needed in order to keep the books for his father’s brickyard, and later his own business. By the time he turned twenty-one, HJ was not only a full partner in his father’s brickyard, but also developing a booming business selling vegetables and horseradish.

The Heinz, Noble Years

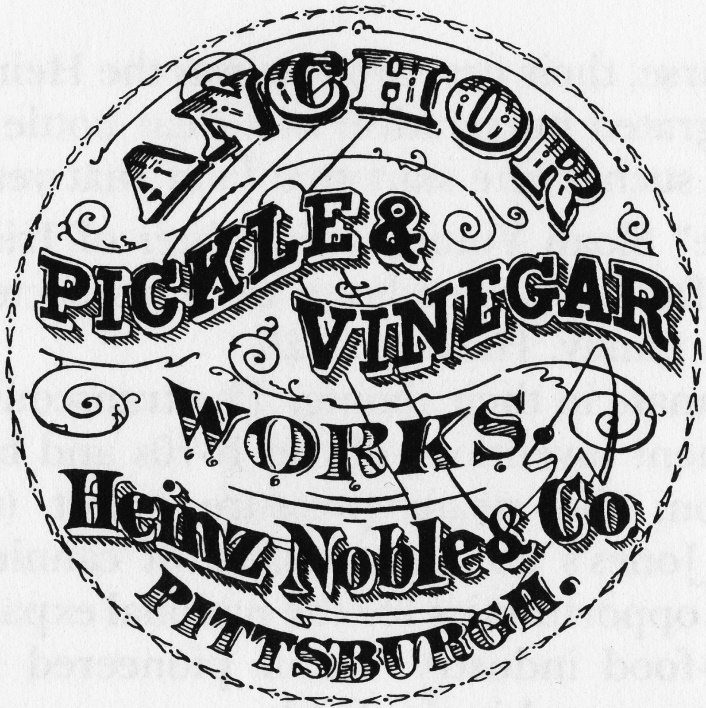

The year 1869 was a momentous one for the twenty-four-year-old HJ Heinz. With his relatively affluent friend Clarence Noble and Noble’s brother, EJ, he formed the aforementioned Heinz, Noble, and Company to make and market horseradish, fruit preserves, mustard, pickles, and catsup. Selling to hotels, restaurants, and grocers in Pittsburgh soon grew to cover neighboring cities, even reaching out into Ohio and the East Coast. HJ used the newly built railroads to the fullest advantage for both supplies and outbound shipments. Business boomed and the company contracted for more cucumber production (for pickles) in the better soils of Illinois.

“Always plenty to do.”

In the other important life event of 1869, HJ married Sarah “Sallie” Young, the daughter of immigrants from Northern Ireland. They had a daughter, Irene, in 1871 and a son, Clarence Noble Heinz, in 1873. While the family continued to live in Sharpsburg, HJ commuted daily to new offices and manufacturing facilities in Pittsburgh, closer to his customers.

The next six years were ones of great growth for Heinz, Noble. Under HJ’s leadership, the company began the extension of its product line, forever testing and adding new products, including sauerkraut and vinegar. They began to develop a “brand,” rare for this time in which most food was sold out of undifferentiated barrels. They used the Heinz, Noble name but also developed the Anchor brand. HJ began early experiments in product differentiation, offering higher and lower quality products at different prices.

The best were offered in custom-designed glass packaging, embossed with the company or brand name. These bottles and jars were aimed at the tabletop of individual customers, supplementing barrels sold to grocers. Every product at all price points was better than what the competition offered. These were unusual practices in post-Civil War America. British firms like Crosse & Blackwell and Lea & Perrins (Worcestershire sauce) knew how to brand and package, but the products they exported to America were high priced and sold only to the wealthiest families and finest hotels. HJ learned new ideas from watching them.

Heinz, Noble became a sizeable company, at peak harvesting season employing 150 people. Each year the company could turn out 500 barrels of sauerkraut, 15,000 barrels of pickles, and 50,000 barrels of vinegar. The company was written up in the Pittsburgh papers as one of the fastest-growing companies in the city.

But, as described in the opening paragraphs above, the Panic of 1873 hit Pittsburgh hard by 1875, bankrupting Heinz, Noble and bringing HJ down into deep personal depression by December 1875.

The Rise to Empire

Nevertheless, by the spring of 1876, Heinz was back on his feet and ready to try again. Because of all the bad press related to the failure of Heinz, Noble, he was reluctant to involve his name in the new enterprise. The family pooled all their remaining resources of $3,000 ($70,000 in today’s dollars) and on February 14, 1876, formed F & J Heinz Company—one-half owned by HJ’s wife, Sarah, and one-sixth each by his cousin, Frederick; his younger brother, John; and his mother, Anna.

HJ worked tirelessly to rebuild the company, using his proven methods and ideas and continually trying new ones. He also vowed to repay all the debts of Heinz, Noble, which took him five years to accomplish. Frictions arose as brother John, a brilliant mechanic and machine designer, did not have the work ethic of HJ. Cousin Frederick was a great gardener and knew plants and seeds, but did not have administrative skills. Family wrangling would continue for twelve years, until the company bought out John’s one-sixth interest for $58,000 in 1888 ($1.6 million today), at which time the company was renamed HJ Heinz, with HJ firmly in control.

In 1880, company sales doubled from $99,000 to $198,000. By 1884, sales were $381,000. By the end of the 1880s, they reached $1.2 million. HJ had more than fifty salesmen on the road, and over five hundred employees in the peak harvest season. He opened dozens of salting stations near the Midwestern cucumber fields in order to keep the products fresh before shipping them to Pittsburgh to be turned into pickles. By the mid-1890s, each year the company used 500 million cucumbers; 600,000 barrels of apples; 100,000 bushels of beans; 500 carloads of cabbage; and 7 million bottles. Full-time employment reached 2,000, with 18,000 at the peak seasons. Sales hit $2.4 million in 1896. By 1900, he had branch offices in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, St. Paul, Cincinnati, Denver, San Francisco, London, and several other cities. More American factories were built, often closer to the fields. More foreign agencies were added around the globe.

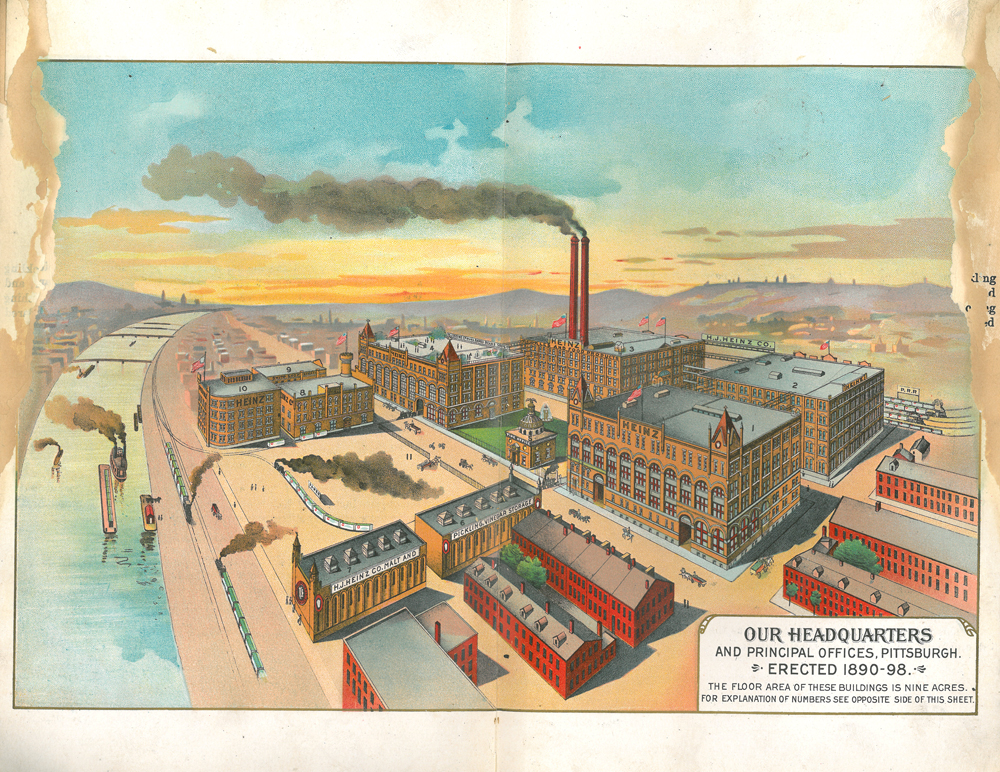

Learning his lesson from the indebted collapse of Heinz, Noble, HJ built the company on its own internal cash flow, avoiding debt. He found that his products had a stable demand, and suffered little in the recessions of 1893 and 1907. He just kept building and building—eighteen beautiful buildings at the main Pittsburgh plant. By 1910, annual sales exceeded $6 million, full-time employment was over 4,000; seasonal workers more than 40,000. The Pittsburgh factory handled 15,000 railroad cars per year. The company operated forty-one branch warehouses and annually used 20 million bottles and 40 million tin cans.

HJ Heinz was relentless in every aspect of the business, an unusually broad entrepreneur. His theme was “soil to consumer,” indicating his desire to control every step from selecting the seeds to placing a beautiful bottle or jar on the family’s table. Many of his ideas were borrowed from others he studied, but he combined these ideas in new ways, developing a fully integrated system of food production. By the 1890s, his company was America’s largest food company and likely the largest in the world. He dominated many markets, including the now-famous tomato ketchup (formerly called catsup). Other companies like Campbell’s in soup, French’s in mustard, and Van Camp’s in beans held their own in narrow categories, but no one had Heinz’s breadth of products as he continually expanded his line.

HJ was also among the first American food processors to go overseas, building a global brand with an especially strong presence in England, where many people believed the company to be English. There he introduced baked beans, which continue to be a staple of the British diet, including at breakfast.

“Mountains and oceans do not furnish any impassable barrier to the extension of trade.”

Though he hired some excellent talent, HJ ran the company very tightly through the mid-1890s. After that, he began to delegate day-to-day control to his son, Howard, and his talented brother-in-law, Sebastian Mueller. This enabled him to travel the world and promote his causes, ranging from Sunday Schools to the temperance movement. But HJ continued to determine the company’s strategy and expansion plans up until his death in 1919, at the age of seventy-five.

The full power of the Heinz “system” and of the man’s innovations can best be understood by considering each aspect of HJ and the business. In almost all these regards, HJ Heinz was years ahead of other food manufacturers, and often ahead of the manufacturers in any industry.

HJ Heinz the Farmer

HJ Heinz was as rooted in the soil as were his precious vegetables and fruits. From childhood through his entire life, he studied which seeds worked best in which types of soil. Using his own knowledge and that of everyone he talked to, the company became more advanced than any other in the food industry.

Over time, he reluctantly hired college-educated food chemists. Every soil, every ingredient, every step of the process was measured, monitored, and tested. He studied and implemented ways to prolong the shelf life of the entire product line. He tossed aside what didn’t work and figured out how to replicate what did.

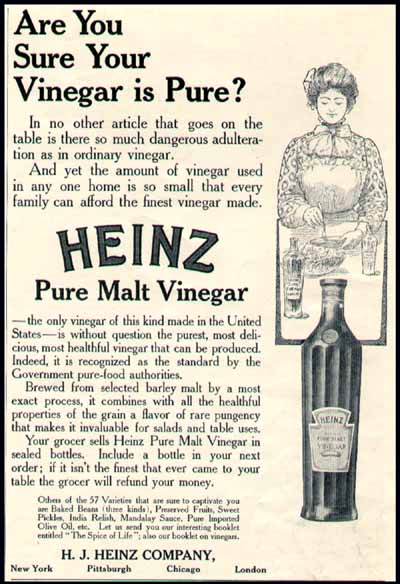

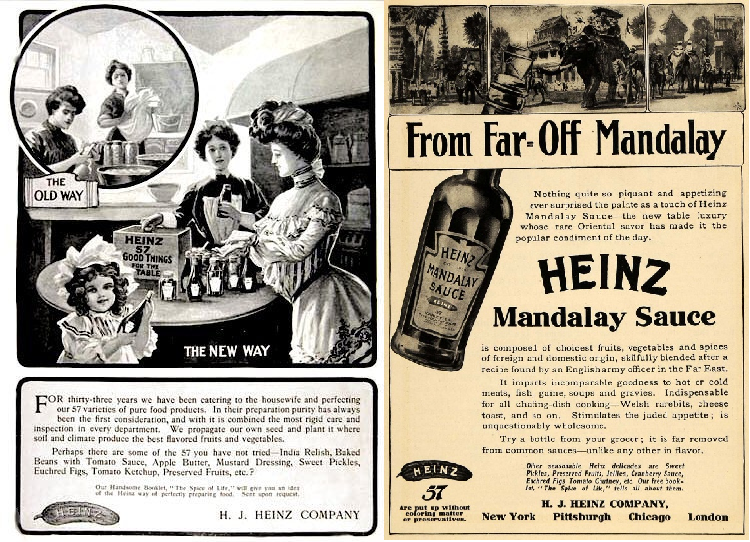

In the early twentieth century, the company teamed up with US Agriculture Department scientist Harvey Wiley to press for the Pure Food and Drug Act. Passage of purity and labeling laws gave Heinz’s company a major competitive advantage, and forced others to stop using adulterated and often dangerous ingredients. HJ made a major point of purity and cleanliness in all his advertising.

HJ Heinz the Manufacturer

Heinz’s innovations and focus on perfection did not stop at the farm. With the aid of brother John, who continued working for the company after he sold out, and later Sebastian Mueller, the Heinz company led the way in the high-volume, efficient production of food products. Over and over again, the company was the first: the first to have a fully electrified factory, the first to produce its own bottles using the latest bottle manufacturing technologies, raising daily production from 350 per worker to 3,500 per worker. HJ was among the first to build modern plants which were spotlessly clean. He had an art department which prepared every label and every ad. Each step of the manufacturing and packaging process was under his control.

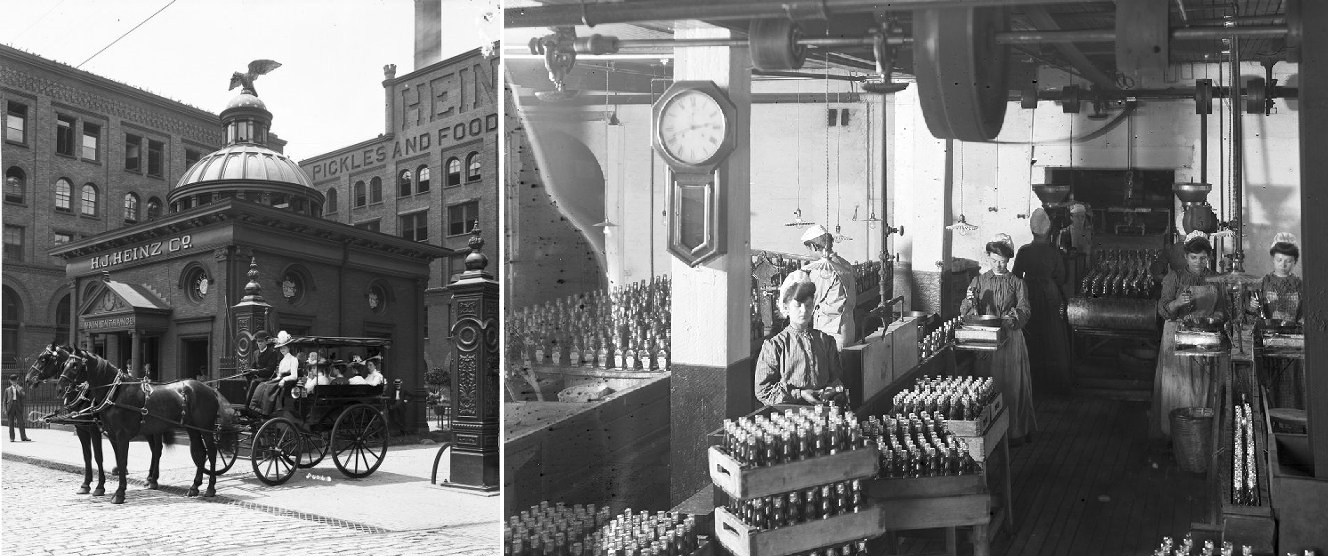

As the company expanded, it built a huge new works on the north shore of the river in Pittsburgh, a temple of manufacturing. Unlike his competition, the factory was open to the public, drawing over 30,000 visitors a year. These visitors were greeted with marble entrances, stained glass windows, murals containing HJ’s favorite slogans, beautiful gardens and landscaping, and plenty of product samples. Even the heated stables for his delivery wagons and horses were cleaned every day. The wagons were washed each day. Every morning, the thousands of workers—largely women—were issued newly laundered uniforms and caps. HJ made the most of this in all his advertising.

Every aspect of the factory was timed and measured and continually improved. He aggressively automated the factory, being among the first to have a true assembly line, many years before Henry Ford. Due to the growth of the business, automation did not lead to layoffs, as new jobs were created.

The bigger the company got, the lower its costs went, as HJ produced his own bottles and cans in huge quantities, and controlled his own fields. Through mass production from farm to the grocer, he was able to lower the price of a bottle of ketchup from $1.75 (one to two days’ wages for most workers) to 35 cents for his best quality and 10 cents for the basic ketchup. (Ketchup of course went on to become his most famous product.) In this way, HJ Heinz made every American family “richer.”

HJ Heinz the Marketer

It was in marketing where HJ shined the brightest—and not just in advertising, but in packaging, distribution, and product differentiation as well.

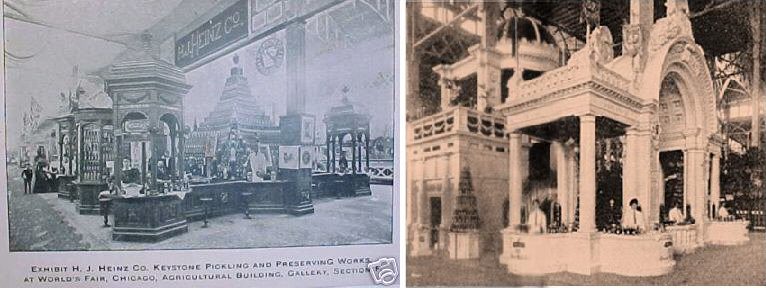

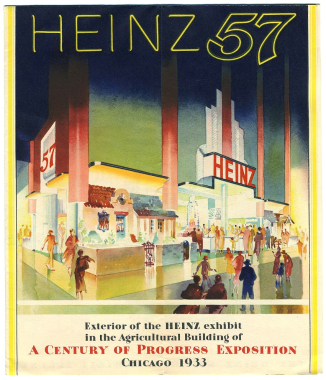

He had a small booth at the great 1876 Centennial Exposition (World’s Fair) in Philadelphia. Filling his ever-present notebooks, he observed the products and methods of other companies, including the British imported food firms and Louisiana’s Tabasco firm, an early branding leader. This experience led him to create lavish exhibits at World’s Fairs, continuing well into the twentieth century. He won gold medals at the 1889 Paris Fair.

At the most-attended fair, the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the best he could do was a second-floor exhibit in the agriculture building. Weary fairgoers were reluctant to climb the forty-four steps up to his product showcase. So HJ distributed coupons all around the fairgrounds, offering a free gift to those who came to his exhibit. The free gift was a pickle pin or pendant. With this bit of promotion, Heinz drew thousands. The second floor of the agriculture building had to be reinforced to hold the weight of the crowds. At the end of the fair, the other agriculture building exhibitors gave HJ an award for how much traffic he had drawn. Pickle pins became pervasive at future fairs.

Early on, HJ realized the importance of distribution and logistics. Most food products were sold to wholesalers who in turn served the local grocers. While Heinz sold to wholesalers, he preferred to go directly to the individual grocers, uncommon at the time. He developed a system of salesmen and “travelers” to visit each store, as well as hotels and restaurants. One of HJ’s highest priorities was hand-selecting and training these salesmen—no drinkers, swearers, or adulterers! Once trained, they went to each grocer, pulling dated products off the shelf (and refunding the money for them), replacing worn labels, and hosting tastings. His people were present at every county and local fair, at church suppers, and at grocers’ conferences.

“Make all you can honestly; save all you can prudently; give all you can wisely.”

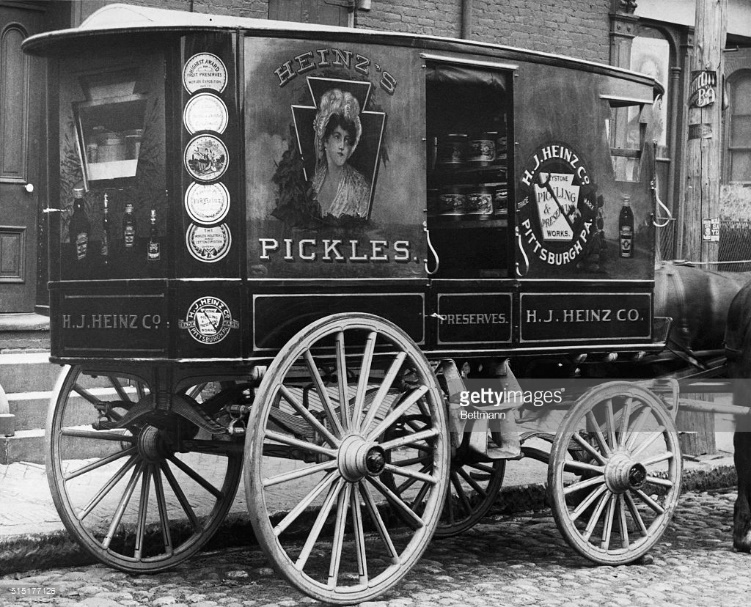

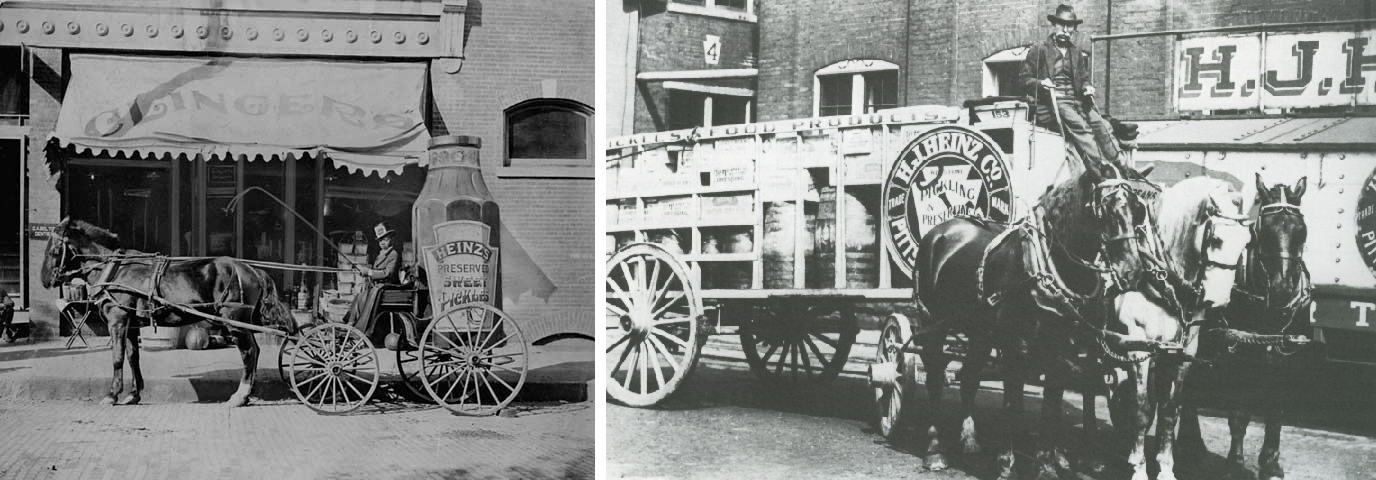

HJ’s products were delivered in bright, beautiful wagons, pulled by a fleet of hundreds of black Percheron draft horses that Heinz had personally selected. He was among the first to use electric trucks, then gasoline powered trucks. The Heinz name and logo were visible everywhere.

He led the way in “transit” advertising. He had signs on the subways and signs alongside the train tracks across America—it was said you could not travel twenty-five miles without seeing one of his signs. HJ Heinz understood the railroads as a tool for distribution and a tool for marketing. He had a fleet of his own railroad cars, all proudly displaying the Heinz brand. He even made some railroad cars and local delivery wagons that were shaped like pickles. His imagination seemed endless.

He had the spark of an idea to hang his fate on a number, something that was easy to remember, and in 1896 adopted the line “57 varieties,” even though he had over a hundred products. Then he put up, in highly visible locations, the giant digits “57” in concrete across the nation, often upsetting the neighbors and local beautification activists.

Heinz put up the first big electric billboard in New York, at 23rd and Broadway where the Flatiron building stands today. With over a thousand incandescent bulbs, it was capable of changing messages frequently.

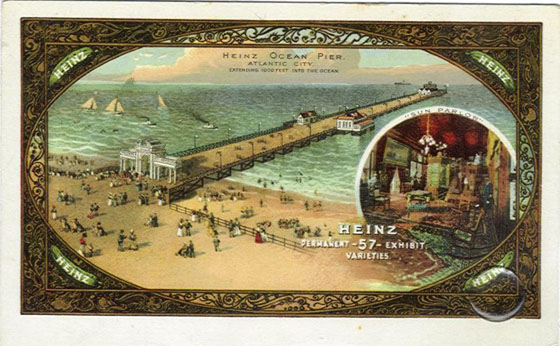

HJ topped all this when he bought the Ocean Pier in Atlantic City, one of the top resorts of the era. Extending out into the Atlantic, the Heinz Ocean Pier offered educational exhibits, lectures, art, music, and product sampling. In peak season, it drew 15,000 people a day. In the first year of owning the Pier, Heinz’s sales jumped an unusually high 30 percent. The pier advertised Heinz products from its 1898 opening until it was destroyed by a hurricane in 1944.

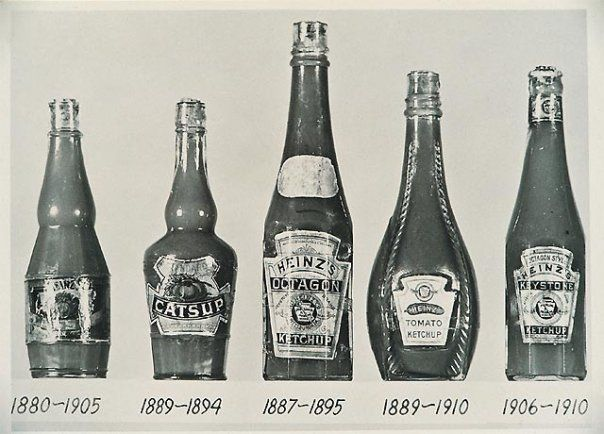

Heinz was obsessed with the branding and packaging of every product. He had his own bottle molds, and protected his designs in court. His famous octagonal ketchup bottle lives on today. Early on, he used clear glass bottles instead of the cheaper brown and green glass, which did not show his pure products well and hid the impurities of his competitors’ foods. He packed pickles and other products in harder-to-find clear wine and malt vinegar rather than the easy-to-find brown apple cider vinegar. He was the first to offer individually packaged bottle of vinegar for use in the home, instead of requiring customers to bring their own buckets to fill from grocers’ barrels.

Heinz made a major innovation in pickles, which previously were sold out of barrels that contained pickles of all sizes. HJ and his associates created machinery that sorted pickles into five sizes, allowing each size to be placed in barrels or bottles and priced accordingly. He also created half-barrels for the convenience of grocers, and put glass tops on the barrels so customers could see what they were getting. Pickles were for many years his most important product.

Learning from his never-ending travels, filling his notebooks, HJ developed separate brands for each market and price point, including the Heinz and Keystone brands. He offered multiple package sizes and product qualities. HJ was always experimenting with new products and keeping the ones that worked, making better use of his manufacturing, distribution, and sales network. When America received a huge wave of immigrants from Italy, HJ added canned spaghetti and macaroni to the product line.

Samples of Heinz products were available everywhere from local fairs to world’s fairs. He set up tastings in grocery stores, using fine china. He distributed and printed millions of recipes. He suggested new uses. By promoting his olive oil and vinegar and suggesting recipes, HJ got Americans to eat more salads.

Gradually, the company began to support the rise of national magazines, becoming one of the largest buyers of advertising space. Son Howard continued these efforts. Heinz’s ads promoted the company’s purity, its clean factories, and always its brands and slogans.

Through all these efforts, HJ Heinz had an enormous impact on the daily lives of Americans and on their lunch pails and dinner tables, a tradition that continues today.

Moreover, branding and advertising today saturate the globe. Every seller of goods and services, from Procter & Gamble and John Deere (both 201 years old) to Samsung and Kia, tries to figure out how to capture our attention and engagement. HJ Heinz was fifty to a hundred years ahead of many companies. Few brands achieve the continuous and pervasive touching of lives accomplished by HJ Heinz.

HJ Heinz the Employer

HJ Heinz was equally remarkable as an employer. When Pittsburgh’s giant steel plants and coal mines offered decent wages but brutal, dirty, dangerous working conditions, Heinz offered an alternative. His factories paid less, but were beautiful environments. They were safe and spotless. He was among the first to provide benefits to his people, alongside fellow Pittsburgher George Westinghouse. The list of benefits was endless: free onsite dental and health care, lunchtime concerts and lectures in the 1,500-seat auditorium, weekend retreats in the country, help with learning English and applying for citizenship, and, rare for the times, the chance for women to become “foremen.” HJ was among the first to let his workers off at noon on Saturdays, and later cut back to a five-day workweek.

“Heart power is stronger than horsepower.”

The wives and daughters of the steel workers and coal miners flocked to these jobs. In the thousands of immigrant families pouring into Pittsburgh, every family member was expected to contribute. The Heinz factory gave young women the chance to do so without endangering their health and lives.

HJ Heinz, however, was a stern taskmaster. He would not abide drinking, swearing, divorce, or adultery. He continually posted slogans and provided lectures on “right living.” Over time he relaxed his limitations on the factory workers, but never backed down on his standards for his executives, foremen, and salesmen.

HJ Heinz the Man Beyond the Business

HJ’s deep religious roots affected his lifelong behavior. Drunkenness was never tolerated. He refused to sell his products to saloons until later years when hotels, restaurants, and bars became integrated. He was a national leader in the temperance movement. He worked hard to encourage his associates and employees to live the “righteous life.”

Despite being such a stern leader, he was always interested in his employees. As he delegated company leadership to others, he annoyed them by meeting with low-level employees and reporting their complaints to management. He continually visited farms, factories, and stores, talking, listening, taking notes, and above all else, selling.

In the early days, HJ used Pittsburgh’s position as a railroad hub to explore America in every direction. He was continually out on the trains, visiting New England, Florida, the West Coast, and everywhere in between—more meetings, more sales pitches, more customers, more stores, more notes.

As he aged, he began a life of more distant travel. His first love was England, where he established a major company presence, ultimately building a large factory. He expanded into his ancestral homeland of Germany before reaching out to Africa, Asia, and Latin America. He became enamored with Egypt, even shipping a mummy home. He took notes everywhere, measured everything. But above all else he promoted Heinz products, always carrying trunks full of his samples to each destination.

Even in his darkest days in 1875, HJ continued teaching Sunday School. He became a national then an international leader in the Sunday School movement, serving on numerous boards. He convinced his fellows to go to Japan, Korea, and China, where they met with mixed success. Despite his Protestant roots, Heinz was ecumenical, working with Catholic, Jewish, and other groups—whatever it took to get people to trust in God and live life the best way. He was a major supporter of YMCAs and YWCAs.

HJ was committed to making Pittsburgh a more livable city. He led fights to reduce pollution and eliminate typhoid, which was epidemic. (His wife, Sarah, died in 1894, likely from typhoid.) He led the efforts to create an exposition center in Pittsburgh to draw tourists and business people. He led the movement toward better city government, and supported progressive Republicans and trust-busters William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. (He had refused to join the canners trust in the late nineteenth century, preferring to control his own destiny and remain independent).

He grew very wealthy, a scion of Pittsburgh. In his world travels, he also became a collector of watches, timepieces, canes, ivories, and other curios—most of which he gave to the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. And when other Pittsburghers like Andrew Carnegie moved to New York or Europe, Heinz stayed in the heart of Pittsburgh where he built his mansion, Greenlawn.

“I am an American in every fiber of my body and in every heartbeat.”

As HJ picked up more and more interests, he retained all his old interests from childhood. His mansion had lavish gardens, with eleven greenhouses and a large staff of gardeners. He collected plants from around the world. He never stopped tinkering with better soils, better products, better packaging, better factories, better treatment of his employees, and better selling, distribution, and marketing. It is unlikely he was ever completely satisfied.

HJ’s gifts to the University of Pittsburgh led to the building of the beautiful Heinz Chapel. His heirs continue to play a key role as civic leaders in Pittsburgh. His great-grandson John became a United States Senator, serving twenty years. After John died in a 1991 airplane accident, his widow, Teresa, married Senator John Kerry, later a Presidential candidate and then Secretary of State.

HJ Heinz’s Legacy

After HJ died in 1919, his son Howard took the reins of the company. In 1941, grandson Jack took over, and led the company until 1966, when for the first time a non-family member was named Chief Executive Officer. Under these leaders and their successors, the Heinz company continued to grow both in the United States and around the world.

In 2013, the 3G Capital Group of Brazil and Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, Inc., acquired the HJ Heinz Company for $23 billion, a 19 percent premium above its previous high stock price. In the prior year, the Heinz company had made a profit of over $1 billion on $11 billion in sales.

Today the Heinz company, now merged with Kraft Foods to become Kraft Heinz, 49 percent owned by public stockholders, sells around 30 percent of the world’s $2 billion-plus ketchup market, the highest market share in company history. It continues to sell other products, and under the new ownership has aggressively promoted newer items like mustard and mayonnaise. It has reduced the additives in its products and focused on purity. HJ Heinz the man would be proud. We can expect this company to keep moving ahead for many more decades.

Sources

This article is largely based on the 2009 biography of Heinz written by Quentin Skrabec, Jr., H.J. Heinz: A Biography. Skrabec has written several books on the great Pittsburgh industrialists. His work tends to be a bit redundant, but thorough and balanced. The first biography of Heinz was written in 1923 by his private secretary, E.D. McCafferty: Henry J. Heinz: A Biography. In 1973, Robert C. Alberts wrote an excellent history of the company, The Good Provider: H.J. Heinz and His 57 Varieties. This was followed up by Eleanor Dienstag’s updated 1994 history, covering 1869 to 1994 and endorsed by the company, In Good Company: 125 Years at the Heinz Table. The Biography TV network produced a good biographical program on Heinz and his family in 2000, but this can be hard to find. Pure Ketchup: A History of America’s National Condiment (2001) by the great food writer Andrew F. Smith gives a broader perspective on the history of ketchup (and catsup!). More can be learned about the company and the man on the Internet, including the museums of Pittsburgh and the Kraft Heinz website.