The technologies of today are built upon those of the past, and the superstars of our era would be nothing without the great leaders of the past. We often discuss our favorite “tech” entrepreneurs. Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Elon Musk, and many other names arise. Too often these discussions lack historical perspective. Here we build a case for George Eastman as the greatest technology entrepreneur. Why does he deserve such a high ranking?

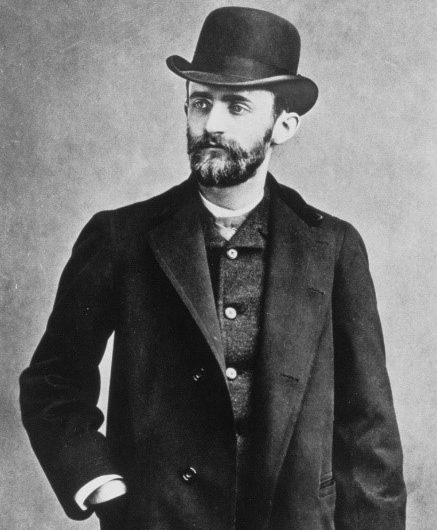

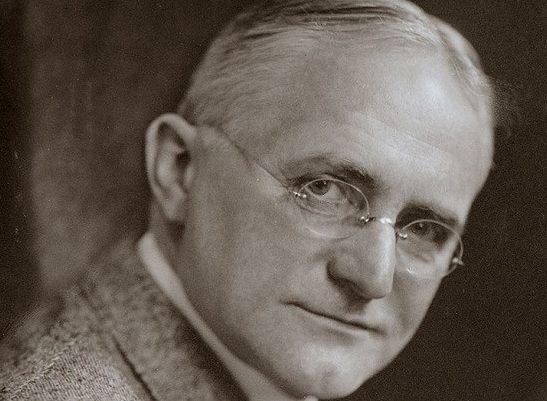

George Eastman, or “GE” as he was called most of his life, was born to a reasonably prosperous family, but his father died in 1862 when the boy was seven years old, forcing his mother to fend for herself and her three children. He became interested in the emerging field of photography and went on to “father” amateur photography with his Kodak cameras and film. Under his leadership, his Eastman Kodak company became a global powerhouse, perhaps still unequaled in its global reach and dominance of an important field.

The company’s innovations led to mass consumer photography, aerial photography, medical x-rays, and the development of the movie industry, precursors to today’s selfies and even YouTube. Eastman was the “total entrepreneur”—marketing genius, financial wizard, great employer, both a visionary and a hands-on inventor and designer. Over the years, he became one of the most important philanthropists in American history, perhaps foreshadowing Bill Gates’s diverse interests. Above all else, George Eastman was “his own man”—a unique personality of independent mind. This is his story.

“If anyone alone decides whether a man is to be promoted it is the man himself.”

The Beginnings

GE was born July 12, 1854, to Maria Kilbourn Eastman and George Washington Eastman, a successful fruit farmer in (far) upstate Waterville, New York. The senior Eastman also operated a business school in much-bigger Rochester which grew into a chain of schools teaching penmanship, accounting, and other business skills. But eight years later, the father died of a “brain disorder.” GE, his two older sisters (one of whom was an invalid), and their mother lived in Rochester, where the family took in boarders to make ends meet.

GE soon became self-reliant, taking a job as an office boy at fourteen. He worked from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., six days a week for $3 a week. Following in his father’s footsteps, he began a lifelong habit of recording every penny he earned and every penny he spent in record books. An entrepreneur at heart, he made and sold little metal puzzles to his friends for ten cents each. For adults, he made $5 walnut bookshelf brackets in his workshop.

Even at this early age, he budgeted to take care of others as well: a ride for invalid sister Katie in a carriage, a book for his other sister, 25 cents a week to the Sunday School coffers. When Katie died a few years later, he paid for her return to Waterville to be buried next to their father.

He also took care of himself, dressing as well as he could afford, two flutes, dancing lessons, membership in a gym, and subscriptions to Harper’s and Youth’s Companion magazines. He even splurged on $10 for a trip to New York City, the beginnings of a lifetime of travel. At age nineteen, he ventured farther afield, to Chicago. He hung around the local bookstore, reading a volume of the encyclopedia at a time while standing in the store. His imagination was fired by tales of geography, travel, and science.

During this time, GE’s mother temporarily took in the Henry Strong family after their home burned down. Henry regaled the families with his stories of adventures—how he ran off to sea as a sailor, jumped ship in France with no money and no ability to speak French, climbed Colorado’s Pike’s Peak in the dead of winter with a caravan of ox teams, and had failed in a business in St. Louis. Later, Henry settled down in the family business, the Strong-Woodbury Whip company, one of the largest makers of whips in the country. Sixteen-year-old GE, forever shy and quiet, and the gregarious thirty-two-year-old Henry were ultimately to do remarkable things together.

By seventeen, GE had joined the Buell & Hayden insurance agency where he made $41.66 a month, along with another $8 for serving as a volunteer fireman. In April 1874, twenty-year-old GE took a $700 per year job as a clerk at the Rochester Savings Bank. Within a year, he was making $1,000 as second assistant bookkeeper, when the average annual wage was $3-400. He was saving money, but he was also spending—on inexpensive art, clothes, travel, and gifts.

“More time and business are lost by a delay in making a decision than in making the wrong decision.”

The Amateur Photographer

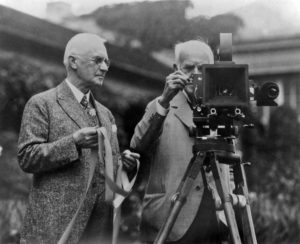

The 1870s brought an important change to Eastman’s life. In 1877, he became interested in investing in land around the new American naval base near Santo Domingo, Hispaniola. He planned a trip to investigate, and a friend recommended he buy a camera to take with him to record the possibilities. The trip never took place, but GE got his first camera and was soon hooked on photography as a hobby. At the time, photography required a serious investment of money and time. His $49.58 “kit” ($1,100 in today’s money) included a camera the size of a soapbox, a tripod, a plate holder for the photographic plates, a darkroom tent, a nitrate bath, and a container for the water required to make pictures. Professional photographers would put up with all the hassles, but there were only two “amateurs” in Rochester, of which Eastman was one. He took classes and talked to experts, learning everything he could about his new interest.

Eastman described the process:

We used the wet collodion process, taking a very clean glass plate and coating it with a thin solution of egg white. This was to make the subsequent emulsion stick. Then we coated the plate with a solution of guncotton and alcohol mixed with bromide salts. When the emulsion was set, but still moist, the plate was dipped into a solution of nitrate of silver, the sensitizing agent. That had to be done in the dark. The plate, wet and shielded from the light, was put in the camera. Now you took your picture.

In a photography journal, GE read of a new process in England, using dry plates instead of wet plates. He began to experiment with formulas himself, and wrote:

My first results did not amount to much, but finally I came across a coating of gelatine and silver bromide that had all the necessary photographic qualities. … At first I wanted to make photography simpler merely for my own convenience, but soon I thought of the possibilities of commercial production.

He continued his successful career as a banker, working on photography in his “spare time”—from 3 p.m. each day until breakfast the next day. He met every photography expert he could, subjecting them to “relentless questioning.” Eastman soon realized the need for a coating machine to uniformly, easily, and cheaply coat the dry plates. He developed one and patented it.

In June of 1879, the twenty-five-year-old used his $400 in savings to take the steamer Abyssinia to Liverpool en route to London, the financial capital of the world. His goal was to patent the machine in England, sell off the rights, and use the proceeds to go into business for himself. He had mixed results—the leading British manufacturers liked his idea and offered to buy it, but dawdled on the final agreement and any payments. While he visited Paris and fell in love with Europe, he said, “Englishmen as a rule are business hyenas.” With this trip, GE already indicated his awareness of the potential of international markets, when few other American businessmen ventured abroad.

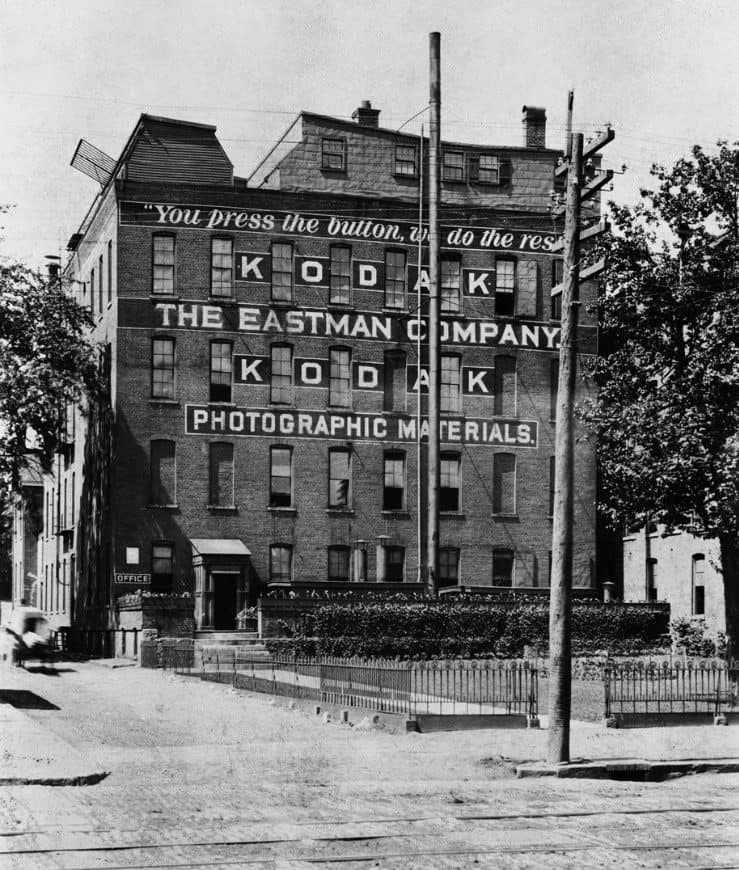

By 1880, Eastman was promoted to first assistant bookkeeper at the bank, with a salary of $1,400 per year. He rented a room above a music store in downtown Rochester, two blocks from his bank, where he could continue his photographic ambitions. As would be demonstrated throughout his lifetime, GE learned everything and paid special attention to details. For his new darkroom, he designed and patented ruby red light globes and had them custom-made by the Corning Glass Works, also of upstate New York. In December 1880, George Eastman and old friend Henry Strong set up the Eastman Dry Plate Company.

He did everything himself, from hiring and firing to inventing, mixing, selling, bookkeeping, and corresponding. He designed and made his own hammock so he could nap during his overnight stints before returning to the bank each morning. He came out with a better coating machine while still trying to sell the patents or rights to the old one. But he kept his bank job, believing he needed a fallback in case the new venture failed. By March of 1881, he had six employees; by December, sixteen. That same year, Henry Strong, now successful in the whip business, invested $5,000 in Eastman’s photography business.

The Independent Businessman

However, in that same year, September of 1881, Eastman was passed over for a promotion at the bank when his superior left—passed over in favor of a relative of one of the bank’s directors. He said, “It wasn’t fair; it wasn’t right; it was against every principle of justice.” He quit, devoting full time to the Eastman Dry Plate Company. One banker said, “George is a damn fool to give up a wonderful position for a will o’ the wisp.”

GE bought land and began construction of a new four-story building for the company. He was producing dry plates, but soon confronted his first business crisis: some of his plates produced no image and others were badly fogged. For two years the plates had been fine, and he could not discover the new problem. He reimbursed all his photographic dealers for the bad plates and soon ran out of money. The contractor threatened to foreclose on the new building, but was convinced to stay the course.

After 469 failed experiments to find the right emulsion to fix the plates, Eastman and Strong again steamed for England to see their chemical supplier in March 1882. In a week, they discovered the problem was the gelatin—the English company had changed its source without telling Eastman. It was not until forty years later that the company realized that the new cows from which the gelatin was made had not grazed on enough sulfur-rich mustard. While in England, he visited his suppliers’ factories and absorbed every detail of their operation.

By 1884, GE was successfully pursuing a “rollable” substance—a way to create roll film. The idea had been around since 1854, but no one had figured it out. Eastman believed that the first company to market a flexible, tough, transparent, inert substitute for glass would have a big advantage over the hundreds of small plate companies struggling to survive. He also developed a roll holder that fit on the back of existing cameras. His 2.75-pound system could take 50 pictures; by comparison, 50 glass plates weighed 50 pounds. In creating this roll holder system, Eastman was an early user of interchangeable parts (seventeen of them). These innovations won the system gold medals at photography exhibitions in London, Paris, Florence, Moscow, Geneva, and Melbourne. By 1885, he had salesmen and demonstrators traveling the world, keeping up with and encouraging them constantly by letter and telegram.

Also in 1884, at the age of thirty, he structured the company as a stock company with $200,000 in capital ($5.4 million today), with thirteen stockholders. Henry Strong had the most, 37.5 percent of the company, followed by Eastman with 32.5 percent. Thus began what became one of the best investments in American history. Eastman soon began the habit of paying for things, even paintings, with company stock.

Despite the honors and publicity earned by his new system, and despite his great selling efforts, professional photographers were slow to switch from dry plates to roll film. And there were few amateurs who would put up with the difficult process and need for a darkroom. Eastman said, “When we started out with our scheme of film photography, we expected that everybody who used glass plates would take up film, but we found that the number which did so was relatively small, and in order to make a large business we would have to reach the general public.” He wanted a camera that “any child could operate.”

As Eastman worked toward this much more ambitious strategy, he continued to experiment with chemicals and emulsions. Over time he hired the best minds he could find. While he had little formal education himself, he began hiring university-trained chemists, alongside self-trained experimenters. In 1886, when his salary was $60 per week, he gave $50 to the local Mechanics Institute, his first gift supporting formal education. As the new men took over his role as experimenter (though he was never far away), he began to focus on marketing. (He also hired many women, who were among his highest paid.) He designed every ad, chose every illustration.

GE also became an expert on patents and patent law; he fought many battles over his own patents and the great many competing patents. He negotiated when that was the best policy, he fought when he needed to, and he often bought other companies for their patents or to gain a key executive or chemist that he wanted. He was ever-present in the factory, often scaring his workers as he walked through the works so silently that they didn’t hear him coming.

“You push the button, we do the rest.”

The Rise to Empire

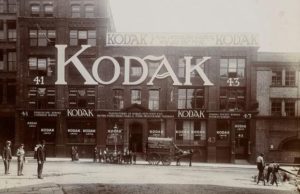

In 1886 and 1887, he developed a small $45 “detective camera” with a removable roll holder with forty-eight pictures, but he was not happy with it and soon stopped production. In the late 1880s, Eastman opened his first retail store, in Oxford Street in London; stores in Paris and elsewhere soon followed. In the winter of 1887–1888, he finally developed a film camera that worked. While owners could develop their own film (requiring sixteen items in a darkroom), the Eastman Company offered the service of developing the film. Send your camera back to us, we will develop the film, reload the camera with new film, and send the camera and finished pictures back to you. The camera with film for one hundred pictures sold for $25, and the developing service cost $10 per roll.

At the same time, Eastman coined the term “Kodak.” While numerous stories exist about the name’s creation, it appears that he liked the “hard” k sound, the fact it could not be misspelled, it could not be mispronounced, was intelligible in any language, and was like no other word. Kodak went on to become one of the most powerful brand names in American history. Eastman’s customers became “Kodakers.” The slogan was “You press the button, we do the rest.” Few technology entrepreneurs have also been so adept at marketing.

Eastman knew he had a hit on his hands when his senior partner and financier, Henry Strong, who had never taken a photograph, took a Kodak on a trip and became obsessed with it. The idea and name spread like wildfire. Gilbert and Sullivan included references to a Kodak in one of their operettas, “Utopia,” and an 1890s song “To My Sweetheart’s Kodak” contained the lyrics:

O Kodak, are you so void of sense

That you so stoically take

The pressure of her fingers fair

While all my nerves do shake?

In six months in 1888, five thousand of these cameras were sold, and the company earned a profit of $269,000, almost double the profit from the same six months of the prior year. Eastman began to attract talent with stock options rather than high salaries. He also realized that the people he hired from around the world might need Rochester to be a better city to live in if the company were going to prosper.

Eastman began his practice of continual improvement. The first camera had no viewfinder, so he added a V-mark on the top that the photographer could point toward the subject. Then he added a card on which the photographer could mark how many pictures they had taken so they’d know when the roll of one hundred was complete. He came out with new models every year, by 1902 making sixty different camera models for every application. Over time he realized that the company’s strength must come from making the best products, improving every year, rather than fighting long, drawn-out, expensive patent suits.

GE soon realized that the sale of film, not cameras, would be the key to the system’s success. He made references to King C. Gillette’s practice of practically giving away razors in order to make money on blades. His over-arching understanding of a complete system set him apart from the many tinkerers and inventors in the photographic field.

Eastman never lost sight of the international markets. With the Rochester plant unable to keep up with demand, he built a large factory in England. In the process, he remarked, “You, in England, are too cautious and afraid of making mistakes. We in the States make our mistakes and straighten them out before you even begin to make them.”

He spent three months in 1889 in London and Paris, taking his beloved mother to galleries, museums, and the theater. He organized a new company in England, then returned to the United States to reorganize the American company with a capitalization of $1 million. Gradually, Eastman became an expert on corporate finance. Later, when London’s powerful bankers would not underwrite a large stock offering because they thought he was a dreamer, Eastman gave up and handled it himself. The offering was oversubscribed.

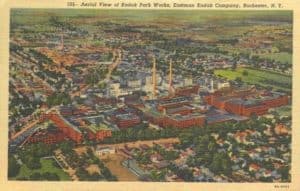

In 1890, he began building a new three-building plant in Rochester. But six months after it was completed, he had to develop plans to double the size. Eastman recalled his rural roots, and loved gardening and landscaping. He did not consider the buildings complete until they were beautifully landscaped. The complex became “Kodak Park,” one of the nation’s most impressive industrial facilities. It included two 366-foot-tall brick smokestacks, taller than any building in New York City, to carry away the factory’s fumes.

Also in 1890, a young Alice Whitney applied to be Eastman’s secretary. She was told he was “a difficult man to work for” but applied anyway. She got the job, and for the next forty-two years was his assistant, his screener, and his protector. She gained power of attorney and wrote checks on his personal account. She was the only one around when he wrote his will, but even she did not see the amounts he put beside each name. For thirty years, Alice Whitney had a courtship with fellow Kodak employee Charlie Hutchinson, and finally married him in 1927. When Charlie died in 1974 at age one hundred, he left more than $25 million to the University of Rochester, the third biggest donor after Eastman and the founder of Rochester-based Xerox, Joseph C. Wilson. That Kodak stock really paid off!

In 1892, the company was renamed the Eastman Kodak Company. While the company had introduced cameras selling for as little as $5, the big breakthrough came with the “Kodak Brownie” of 1900. It sold for $1, the film for fifteen cents. Hundreds of thousands were quickly sold.

During these same years, Kodak took the lead in making film for the motion picture industry. The company’s product was undeniably the best, and production could not keep up with demand. For many years, cinema film was a more important source of revenue than consumer film. Eastman established one of the nation’s first industrial research laboratories. The company went on to play a leading role in film for x-ray machines, and pioneered cameras for aerial photography, operating a school for the US military during World War I. (And Eastman gave back to the government his wartime profits.) During the war, precious chemicals from the great German chemical companies became unavailable. So, by the 1920s, the company had developed a synthetic chemical department, ultimately to become the Eastman Chemical Company of today, which in 2016 earned a profit of $854 million on sales of over $9 billion. Color still film and color movies came along in time, led by Kodak in pursuit of the longstanding dreams of the founder.

By 1895, the company made 90 percent of the film produced in the world. The Eastman Kodak Company achieved and maintained this almost-monopoly market share without the government protections held by companies like AT&T. It had patents, but above all else it had the skills and leadership required. The original leaders of the photographic industry, Anthony of New York City and Scovill of Connecticut, merged to form Ansco, but never again rivaled Kodak. In the trust-busting era, especially under President Woodrow Wilson, the government sued to break up Kodak—the trial and negotiations went on for years before an agreement was reached, with little impact on the company. Perhaps the regulators realized that a decline in Kodak would mean the rise of the German industry, especially AGFA.

By 1913, the market value of all Kodak stock reached $175 million, making George Eastman one of the richest men in America, and showering other Rochester residents with wealth. In 1967, Kodak was the third most-valuable company in America, behind only IBM and AT&T. It was worth more than Standard Oil of New Jersey (later called Exxon) and General Electric combined. In 1973, the value of the company reached $24 billion.

“What we do during our working hours determines what we have; what we do in our leisure hours determines what we are.”

George Eastman the Man, and his People

Despite his success, Eastman was painfully shy throughout his life. He refused to attend events honoring him, made few speeches, and was often mistaken for being cold and aloof. He disliked interviews and personal press coverage, killing efforts to write his biography. He had great powers of concentration, and visitors often awoke him from a fog of thought. Nevertheless, as is common among people of such complexity, he had his contradictions. He developed an enormous range of personal friends around the world, entertained them lavishly, and traveled in large groups, often in a chartered private railroad car.

His friendships were complex. Those who were loyal, who worked hard and were able to maintain his almost-impossible quality standards prospered. Those who left to join the competition were never spoken to again. He had spies go into competing factories to see if they were using his patents. He even had detectives follow his salesmen to see if they were doing as they were instructed.

Those who performed were amply rewarded. He said, “The past and continued prosperity of our company is not due to the value of a patent or an invention. Quality can only be secured by extreme skill and alertness not only as individuals but as an organization.” The Eastman Kodak Company was a leader in offering employee amenities—recreational areas, health care and insurance programs, and pension benefits. Eastman Kodak was an early user of employee suggestion boxes. The biggest innovation was the “wage dividend,” begun in 1912. Each spring, every employee, at every level, received a bonus check of 2 percent of their wages for the past five years, or about five weeks’ pay. Kodak Bonus Day became a retail holiday in Rochester. By 1914, the company had ten thousand employees. In 1989, the payout to 85,000 employees was $239 million.

In 1919, Eastman gave one-third of his own stock to an employee pool, worth $5 million, and matched it with company treasury stock. Employees could buy stock, then selling at $575 per share, for the $100 par value. In 1924, he contributed another $9 million of his own stock. Due to a happy workforce, the company was never unionized. Virtually all executives were promoted from within. Eastman Kodak had among the lowest employee turnover rates in American industry—less than 10 percent per year.

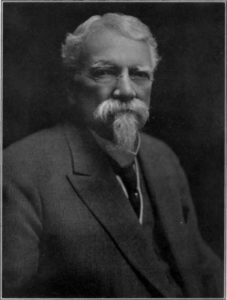

Despite appearing to be a “control freak,” Eastman believed in delegation, and would frequently go on long trips and leave the day-to-day work to his trusted associates. Beginning in 1921, at the age of sixty-seven, he reduced his daily visits to the office, and retired from the presidency of Eastman Kodak in 1925 to let the “next generation” take over. The company was in good hands.

Another unique aspect of Eastman, rare for his era, was that he never married, remaining a bachelor his entire life. At the same time, he was always surrounded by women and shared many of their interests, from gardening to cooking. He loved children and took care of his many relatives and their offspring. He entertained and traveled with women around the world. Several pursued him to no avail. All efforts to learn more about his sexuality have failed; it’s clear that he was heterosexual, but there is no evidence of any affairs. He may have fallen in love early and lost. Perhaps he sublimated his energy into his never-ending projects. There is no question that he was shy, and that he prized his independence.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about George Eastman was his diversity of interests. He leaped from project to project, becoming an expert in each, talking to experts, reading everything he could get his hands on, and then developing a clear, comprehensive plan. His interests included gardening, cows, horses, bicycling, automobiles, music, travel, art, reading, higher education (including for blacks in the South), guns, children’s dentistry, the health of the poor, housing for the poor, silent movies, the Chamber of Commerce, cooking, best practices in municipal government, hunting, fishing, and politics (though he stayed in the background there). He wrote over two hundred thousand letters in his lifetime.

While he always had a broad, strategic vision for each project, he never missed a detail. His life was full of the smallest achievements: when workers misplaced tools, he put hooks on the wall and drew the outline of each tool on the wall so none would ever be misplaced. He designed a custom picnic basket for the frequent automobile tours with his friends. He looked hard at the pipes and plumbing fixtures in every building he was involved in … and on and on and on, in every aspect of his life.

Perhaps above all else, he loved architecture and was a continual nettle to his high-priced architects, including the famous New York firm of McKim, Mead, and White. He designed the floor plan of every building he was involved with, from factories to houses to theaters, before he let the architects “decorate it.” He always sought the very best and most durable materials while at the same time watching every penny for waste or needless extravagance. He was a leader in factory construction and became one of the nation’s top experts on fireproofing because of the flammable nature of the chemicals used by the company (and the experience of an early fire).

George Eastman the Spender and Giver

While Eastman could be generous, he was also good to himself. He owned Packards, Lincolns, Cadillacs, and a custom-made Cunningham automobile. He traveled all over the United States, often six weeks at a time, and took an entourage of friends, relatives, and work associates with him. He bicycled around Europe, and later ventured to Africa to hunt big game and take pictures. He took a long trip to Japan.

George Eastman’s ideas and actions were always big and bold. He took his first airplane ride in 1918, a brave thing to do, and later rode in the Goodyear blimp. He climbed mountains. He bought gifts for his friends and employees, and art for himself. He went to the theater nightly when in the cities. He hired the finest musicians to come to Rochester to play for him and for the public. He threw massive parties and events at his house and at the company.

His greatest extravagance was his 1905 mansion, Eastman House. The 42,000-square-foot palace had thirty-seven rooms and thirteen baths and was surrounded by acres of flowers and gardens. Given Eastman’s love of music, the house included a huge custom-built pipe organ, which was later expanded and a second organ added. There was a staff of forty inside and fifteen outside to care for the grounds. Even the maids had a maid. Every Wednesday evening and every Sunday, GE held concerts for his friends and family. He frequently entertained lavish events, despite his inherent shyness.

But no matter how much he spent on himself, he gave most of his wealth away. He did not believe in leaving money for a foundation; he wanted to “see the action” himself. A list of his activities and charities would fill a book. He began free dentistry clinics for poor children in Rochester, believing that prevention was as important as curative work. He expanded this system across the capitals of Europe. A lifelong Republican, he fought his old friend the Republican mayor to press through a city-manager system of government which he believed to be more efficient. He supported Margaret Sanger’s birth control movement. He gave massive amounts of money to the black Tuskegee and Hampton Institutes at the urging of his friend Booker T. Washington. He led the campaign for and designed the Chamber of Commerce building in Rochester, and did the same for orphanages, hospitals, the YMCA, and many other local projects. As he finished each project, he would write, “My work in this area is done” and move his money on to the next idea.

In 1924, he became enamored with the idea of a better calendar—in Eastman’s mind, there was always a better way to do things. British statistician Moses Cotsworth had come up with a year of thirteen months of twenty-eight days each, the extra month falling between June and July and named “Sol,” along with one extra day at the end of each year, a “Peace Day” holiday. Compared to the standard Gregorian calendar, the Cotsworth system meant that weekly, monthly, and annual sales and other records were directly comparable, with the number of weekends the same in each month. Eastman Kodak adopted the system in 1928 and used it until 1989.

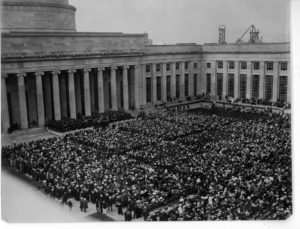

In perhaps his most audacious move, in 1913 he financed an entire new campus for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), from which he had hired some of his best chemists. However, he asked that his $3 million gift remain anonymous for as long as possible, so the university announced that a “Mr. Smith” had funded the new campus. Newspapers raged with rumors as to who Mr. Smith might be. No one suspected Eastman, who was not yet known nationally as a philanthropist. At the same time, Eastman, who always had a prankish nature, gave the university $300,000 for one building, and let them publicize his name. When the buildings opened in 1916, events were held around the United States to celebrate. As a $300,000 donor, Eastman attended the Rochester gathering, where he joined others in praising the unknown Mr. Smith. With later gifts of Kodak stock, Eastman’s role became public knowledge. His gifts to MIT eventually totaled $20 million.

One of the projects he loved most was the Eastman Theater. He spent about $17 million building the 3,500-seat theater, one of the most beautiful in the United States. His visionary scheme was to show silent movies backed by an organ and fifty-member orchestra six days a week, then use the proceeds to finance the Symphony Orchestra which played serious music once a week in the same hall. He believed that the world had enough performers but needed more (educated) listeners. He visited the theater each evening to count the receipts, and often previewed movies until two in the morning. He made the concerts accessible to all. But when talkies replaced silent movies, the revenue concept failed, one of his bigger disappointments.

Eastman also drove the creation of the Eastman School of Music, drawing the finest students and teachers from around the world, but also offering free or inexpensive music classes to local children. In recent years, the Eastman School of Music has been rated #1 in the United States, continuing his legacy of excellence.

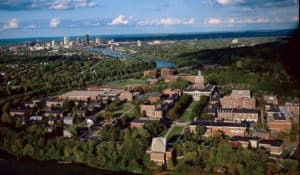

Above all else, Eastman drove the development of the University of Rochester, picking the best university president, and building a new campus. His lifetime gifts to the university, which absorbed the Eastman School of Music, totaled $50 million.

Taken together, between 1910 and 1932, Eastman gave away about $100 million, the equivalent of $1.2 billion in today’s dollars. In most cases, his gifts depended on others putting up additional funds, a very modern approach to philanthropy.

“I don’t believe in men waiting until they are ready to die before using any of their money for helpful purposes.”

Going out with a Bang

Eastman was stoic about death. He did not fear it. Throughout his life, he refused to support religious charities, believing them worthwhile but not subscribing to their beliefs himself. He might be considered an ethical humanist in today’s language. Given his shy nature, when he retired from the company, he said, “I just want to fade away, not go out with a bang.” But that is not quite how things turned out.

By the end of the 1920s, he had become less able to travel. Heart disease, a spinal ailment, and other infirmities held him back. He had trouble walking. Having been active and energetic all his life, his spirits sunk. Reading his biography, one must believe his condition worsened when his nurses and housekeepers kept his old friends away, or limited their visits.

When his doctor came to visit, he asked him to draw an outline on his chest where his heart was.

On Monday, March 14, 1932, at the age of seventy-seven, he dictated a few letters and made final revisions to his will. After the others had left, he smoked one last Lucky Strike cigarette, folded a wet towel over his chest to prevent powder burns, and pointed a Luger automatic gun at the outline of his heart and pulled the trigger. He left a note,

To my friends

My work is done – Why wait?

GE

George Eastman was cremated, as he believed cemeteries “cluttered” the landscape. At his funeral, per his wishes, the last organ piece was Gounod’s triumphant “Marche Romaine,” unusual for a funeral. People and messages came from around the world to wish the old man off. His hundreds of old friends wept openly.

The Legacy of George Eastman

This writer has spent the last fifty-five years studying the business and other great men and women of the past and present. Each of these great people is fascinating, and often complex, almost beyond understanding. Today we honor the Jeff Bezos’s and Elon Musk’s of the world. In the past we have learned much from the stories of Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller, two of the very few philanthropists who gave away even more money than Eastman. Each of these great contributors to our life today had strengths and weaknesses. Edison was a great inventor but not such a successful entrepreneur and business builder. Thomas Watson Sr. of IBM was a great business builder but not a keen inventor. Henry Ford’s affordable car gave freedom to people around the world, especially women, but he had personality flaws that eventually allowed General Motors to become far larger. Alfred Sloan who made General Motors great may have been the best manager in history, but he was not there at the beginning. Steve Jobs was a genius in many ways but not a very generous person.

George Eastman was different. He not only gave of his wealth, he gave of himself. He started with nothing and pursued a dream; not just a product or an invention, but a whole system that would allow “any child” to take photographs. Few technologies have had a greater impact on society than photography—from solving crimes to promoting revolutions, from sharing movies around the globe to taking selfies. His company consistently made better products for lower prices, and provided wonderful jobs and careers. This complex man had an uncanny ability to move quickly between the broadest marketing and financial strategies to designing household improvements and making buildings stronger and better. It is hard to imagine anyone who has had a greater and more pervasive impact on our lives today.

The company he built may have been the first truly global powerhouse. It dominated its field not just in the United States, but in every corner of the world. In the late twentieth century, the yellow Kodak emblem could be found in the remotest villages on earth.

Over time, his great company went into decline. While Eastman Kodak developed the first digital camera, successive leaders failed to make the transition from film to digital. Sales in 2005 were $11 billion, but by 2012 they had declined to $4 billion. The next year the company went bankrupt and was broken into pieces. The famous lines of Kodak film are no longer manufactured, though Eastman Chemical continues to thrive. Much has been written on the company’s decline. But we must remember that technology companies, by definition, are likely to have short lives. IBM’s glory days did not last forever. RCA, the world’s top consumer electronics company, is no more. Sony is in decline as new competitors arise from Korea and China. Only time will tell if today’s crop of great technology companies can live strong and generously for over one hundred years, as did George Eastman’s company.

Nevertheless, it appears certain that MIT, the Tuskegee Institute, the University of Rochester with its Eastman School of Music, and his many buildings in Rochester will survive the test of time—as will the many other contributions made by others made wealthy by Kodak stock, such as Rochester’s world-class Museum of Play.

This biographical sketch is based on the excellent and exhaustive biography of Eastman, George Eastman: A Biography, written by Elizabeth Brayer in 2006.