Before there was Amazon, there was Sears, Roebuck, using the mail-order catalog where the Internet is used today. Before Walmart was the world’s largest retailer (and company of any type), there was Sears, Roebuck, in its glory days by far the largest retailer on earth.

Today, most observers (and shoppers) witness the continuing decline of this once-great company. Nevertheless, the history of Sears and the people who built it provides deep lessons for any entrepreneur, business leader, or marketer.

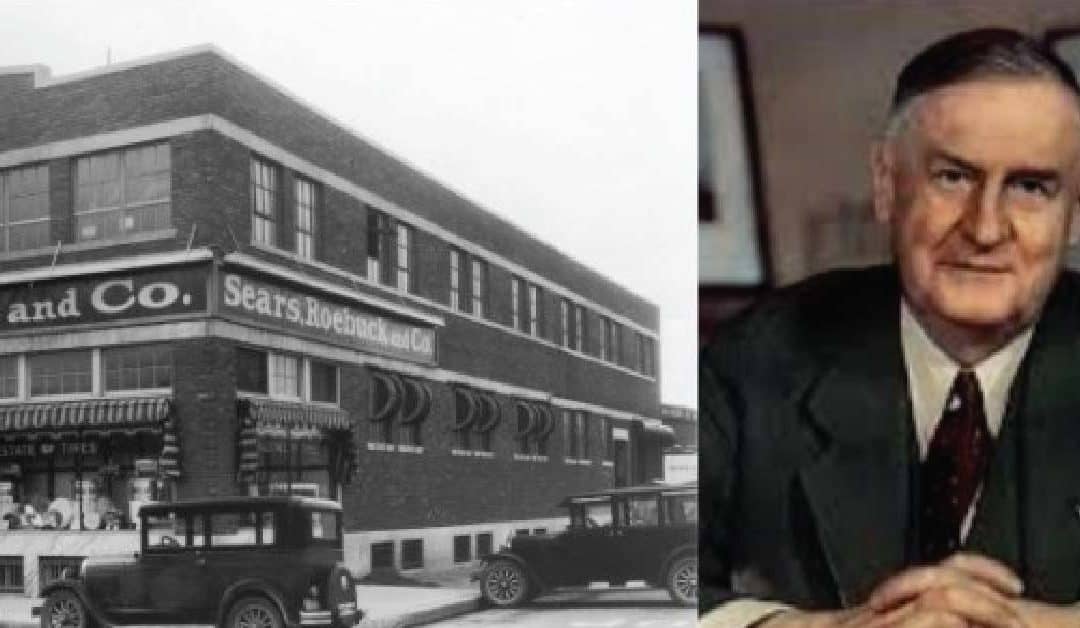

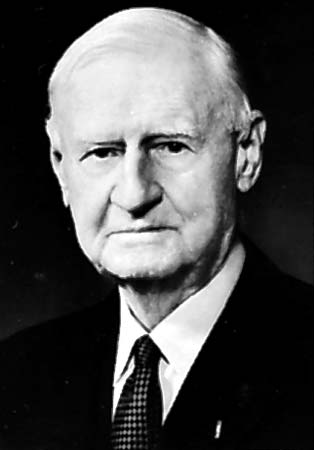

Yet few know the real story behind the two visionaries who made Sears great—neither of whom was named Sears or Roebuck. This is the story of the greatest of them, General Robert Elkington Wood, who shaped so many things about America and the world.

“All the ability in the world is useless without character.”

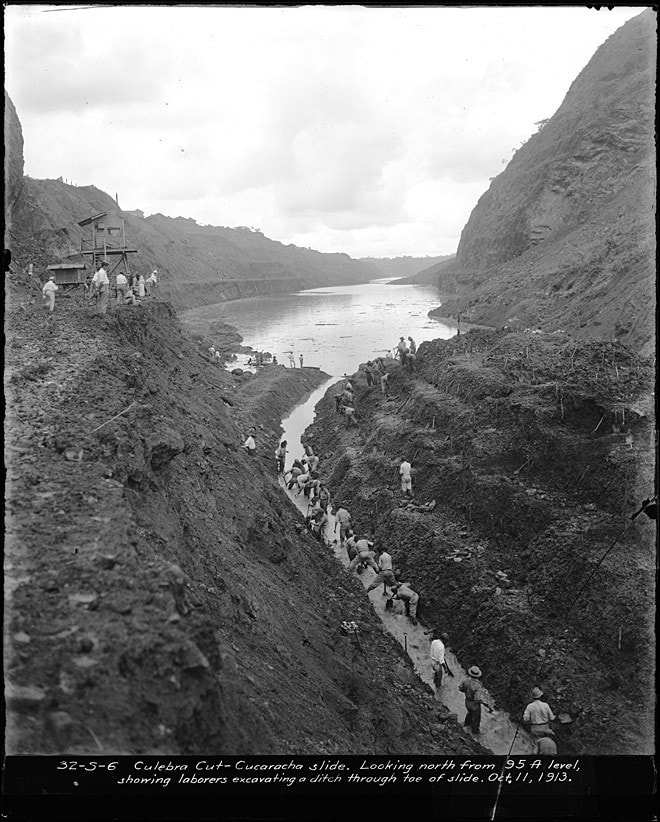

Robert Wood: Building the Panama Canal, Winning World War I

Born on June 13, 1879, in Kansas City, Missouri, to Robert Whitney Wood and Lillie Collins Wood, Robert E. was the first of five children. His father was a decorated Union soldier who fought to keep Kansas free of slavery and went on to become a successful coal and ice merchant in Kansas City. The financial panic (depression) of 1893 lingered on, and by the time young Robert was ready for college, the funds were not there. Intent on continuing his education, his eyes turned to the military academies, where college would be paid for by the federal government.

At the time, admission to the service academies was handed out by members of Congress, who were loyal to members of their own parties. While Robert’s congressman was a Democrat, his father was a staunch Republican. Unwilling to let tradition stand in the way of his progress, he convinced the congressman to test applicants and send the best to West Point. Robert won the battle and in 1896 enrolled at the army’s college along the Hudson River in New York, the youngest in his class. While he excelled in math, his unkempt appearance and less-than-perfect housekeeping earned him many demerits. He later said that, though he appreciated the education, he “hated the discipline.” In 1900, he graduated thirteenth out of a class of fifty-four.

Robert Wood spent the next two years chasing guerilla fighters in the northern Philippines. At the age of twenty-one, he was promoted to first lieutenant, in command of a cavalry troop of one hundred men and one hundred horses. Wood later said, “In my little town of 6,000, the troop commander was the mayor, the judge, he decided ownership of chickens, of animals, even of wives. So it was a great experience for a young man.”

Next came a stint at Fort Assiniboine, Montana, where he had plenty of time to pursue his love of riding horses, hunting, and fishing. Then when he was assigned to teach French at West Point, he discovered he was not cut out to be a teacher. During this time he also met Mary Hardwick, who became his wife in 1908 and soon the mother of their five children.

In 1905, American work was beginning on the Panama Canal, after a failed 1881 French attempt to shorten the seagoing route from Asia to the East Coast and Europe to the West Coast. The French gave up because of extreme engineering challenges and the high rate of worker deaths. The prospect of another attempt excited Wood, and he applied for service there, despite the fact that many who worked on the canal were contracting yellow fever, malaria, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and intestinal diseases. In the summer of 1905, three-quarters of the Americans working on the canal fled for home. Wood was undeterred.

With top officers and even second-in-commands running for home, the opportunity to rise was great. And rise Wood did. He was soon a key assistant to top administrator John Stevens. In 1907, Stevens was replaced by the brilliant engineer General George Goethals, who saw the canal through to completion in 1915. While Goethals obsessed on building the canal, he was not interested in the “little” details—like securing enormous amounts of cement; scheduling the production and arrival of supplies; managing the ports; or feeding, clothing, and housing fifty thousand workers. These tasks were assigned to the young Robert Wood. He even bought locomotives and helped run the railroad in Panama. Tough taskmaster Goethals told Wood, “The day we run out of cement, you’re fired.” Wood later said of Goethals, “I was his assistant for seven years, and I might say that everything in my life since has been comparatively easy.”

“I never loved a job like that Canal.”

Wood worked hard to keep the laborers happy. When he noticed “Lebanese and East Indian” merchants overcharging the locals, he unsuccessfully suggested that the canal company set up retail stores. As the canal neared completion, it was observed that the Americans who had survived the ordeal would have worked for free just to see the first ship pass through. In his key role on the canal, Wood learned a great deal about purchasing large quantities of material and overseeing thousands of workers.

One of his greatest educations was in “supply chain management,” as it would be called today. In determining the prices charged the government, Wood often found suppliers making too much profit, or sometimes too little. He sat down with the suppliers and figured out ways to make their factories more efficient. In some cases, he helped them buy raw materials in larger quantities, lowering the final price. He became an expert in transporting these materials efficiently, what we now term “logistics.”

Throughout his life, Robert Wood was a voracious reader, especially of history and biography. But at the canal, there was nothing to read but government publications lying around. Wood picked up census reports and became fascinated by the data within them. He became an expert on demographics and trends. According to legend, probably based in fact, he read a new table from the Statistical Abstract of the United States, the nation’s most important fact book, each day during his later career.

Through his role in successfully completing the canal, he made a real contribution to the expansion of world commerce. At age thirty-five, Wood was made a major and allowed early retirement due to his service. Then followed a brief stint with the DuPont gunpowder works, where he realized he could not rise past the DuPont family members. Next was a year and a half at the General Asphalt Company, where he was in charge of all production in the United States, Venezuela, and Trinidad.

Then, on April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany, and Wood felt obligated to return to the service. His West Point acquaintance General Douglas MacArthur appointed him a colonel, and Wood was off to Europe. Due to Wood’s experience overseeing port operations in Panama, General John J. Pershing put Colonel Wood in charge of getting supplies to the soldiers on the European front. Wood soon eliminated critical bottlenecks by finding able men and giving them authority.

With the support of high-ranking officers, including General Goethals, Wood was recalled to Washington and named acting quartermaster general, in charge of all supplies for the Allied Expeditionary Forces. He was called “acting” because the quartermaster general’s position had always been filled from the Quartermaster Corps. But the generals picked Wood over members of the corps due to his track record. During his tenure, the Quartermaster Department expanded from three hundred men to ten thousand. By the end of World War I, Wood had been awarded the Distinguished Service Medal and been promoted to general, a title he used the rest of his life.

Robert Wood Becomes a Retailer

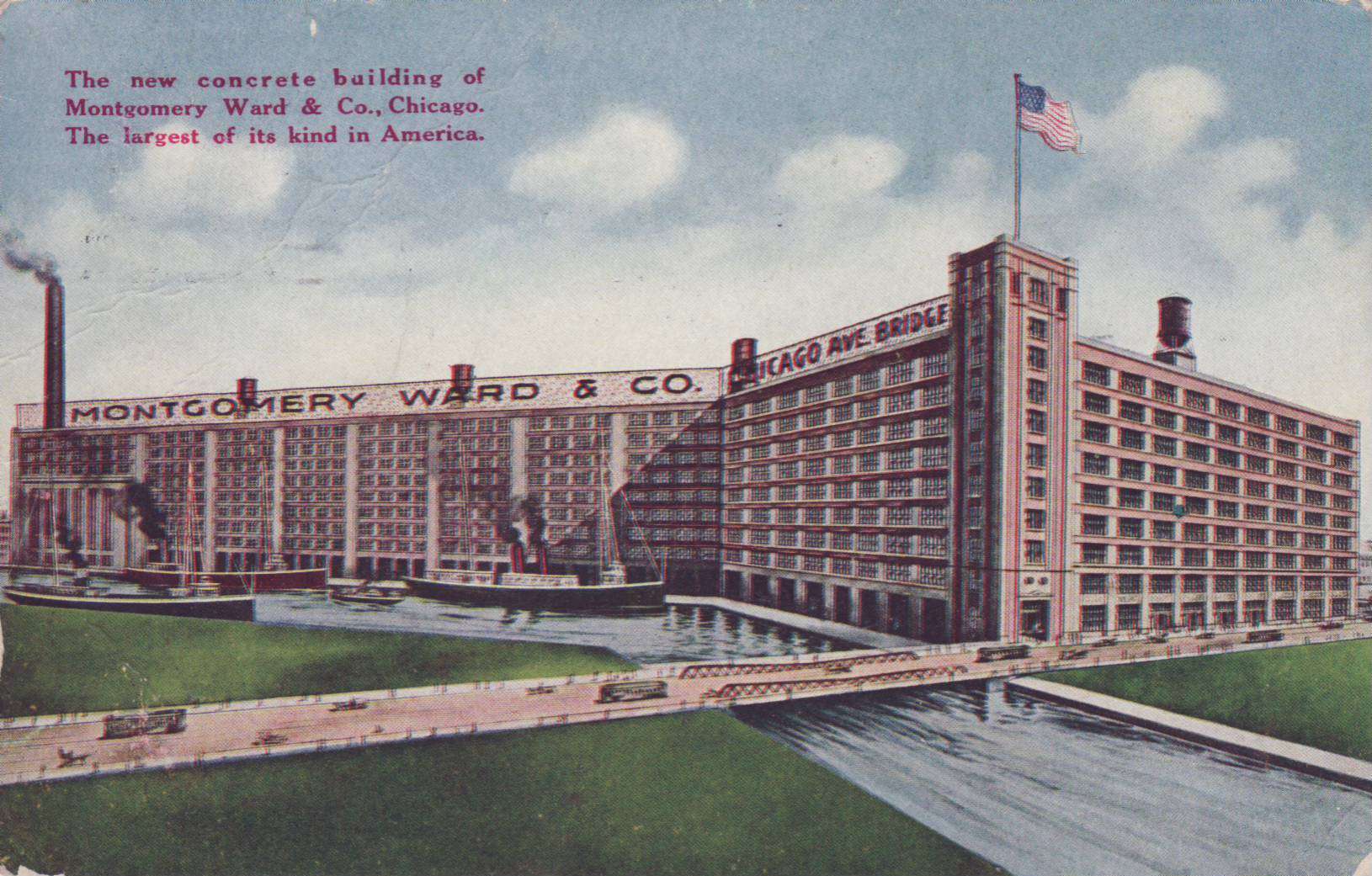

Robert Thorne had been a civilian on Wood’s wartime staff and was duly impressed by Wood’s intelligence and leadership skills. Thorne also happened to be the president of Montgomery Ward & Co., the first big US mail-order house and, since 1900, second only to Sears, Roebuck. Thorne and his four brothers owned a controlling interest in the giant retailer.

In 1919, forty-year-old General Wood joined Montgomery Ward, rising to the position of vice president. Like Sears, Ward’s business was almost entirely dependent on the American farmer. Both mail-order companies had enriched these farmers by carrying the right products at affordable prices.

Wood put his experience in securing low prices for the federal government to work for Ward’s. When he went to buy tires—a key category at Ward’s—he found that the tire companies asked high prices for long-term contracts. Going deeper into the economics of the tire industry, he found that rubber prices fluctuated wildly, requiring the tire companies to charge prices high enough to cover spikes in rubber prices. Wood changed the system. Ward’s would buy the rubber and use hedging to lock in long-term prices, then supply the rubber to the tire companies. Ward’s tire prices came down and that part of the business boomed.

Wood also began to develop long-term relationships with the suppliers of the best quality products. Previously, both Ward’s and Sears had bought their goods one order at a time, negotiating the price on each order, pitting suppliers against each other. But Wood picked the best suppliers, worked with them to keep costs down, and committed to multi-year purchases. Ward’s giant orders saved suppliers the expenses of advertising and staffing a large sales force. Both Ward’s and the suppliers realized higher profits while Ward’s customers saved money.

At the same time that Ward’s better served its farmer customers, Wood’s studies of census and other data led him to foresee a shrinking rural market, in large part due to farm tractors and automation, coupled with a rising urban market. The advent of the Model T Ford and the rise of the automobile meant that even farmers could avail themselves of the broad selections and sometimes low prices of retail stores in the cities. Wood urged his bosses at Ward’s to build retail stores in cities, to no avail.

Robert Wood spent four and a half years at Montgomery Ward, contributing substantially to the company’s success. Ward’s began to close the revenue gap to leader Sears in the early 1920s. But the company’s refusal to consider opening retail stores frustrated Wood, and soon the disagreement with other Ward’s leaders was too great for either side. By late 1924, Wood was either fired or quit, depending on which side one listens to. To understand his next move, we need to step backwards a bit in history.

Sears Before Robert Wood

Richard Sears dreamed of becoming a banker. However, in 1886, the twenty-three-year-old Sears was a station agent for the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railroad in North Redwood, Minnesota. Handling incoming and outgoing freight, he received a shipment of watches that the local jewelry store refused. He contacted the shipper, which offered him the watches, which normally sold for $25, at a bargain price of $12 each. Sears offered the watches to other station agents at $14 so they could resell them at higher prices, and was soon in the watch business. Sears, a brilliant copywriter who understood the needs of farmers, soon issued a catalog, added other merchandise, and moved his business to the railroad center of America, Chicago. When defective watches were returned, he hired watch repairman Alvah Roebuck, hoping Roebuck would take over the company, allowing the newly rich Sears to become a banker. But the easy-going Roebuck did not want to replace the workaholic Sears, and by 1895 Roebuck wanted to sell his share of the company, now called Sears, Roebuck and Co.

One of Sears’s suppliers of menswear was Julius Rosenwald. In 1895, Rosenwald and his brother-in-law each bought a one-quarter interest in Sears, Roebuck. By 1900, after a series of transactions, the brother-in-law was out and Richard Sears played a lesser role. Julius Rosenwald took over both the management and primary ownership of the company.

Rosenwald’s impact on Sears (the company) was immense. While Sears (the man) never paid much attention to product quality—he just sold whatever he could buy cheap—Rosenwald looked for the best products. He focused on what customers wanted and needed rather than on what the company could find to sell. He established product testing laboratories to ensure the best products. Rosenwald dramatically expanded the categories of products that were listed in the catalog—at its peak, the company even sold 150,000 “kit houses,” many of which are still standing.

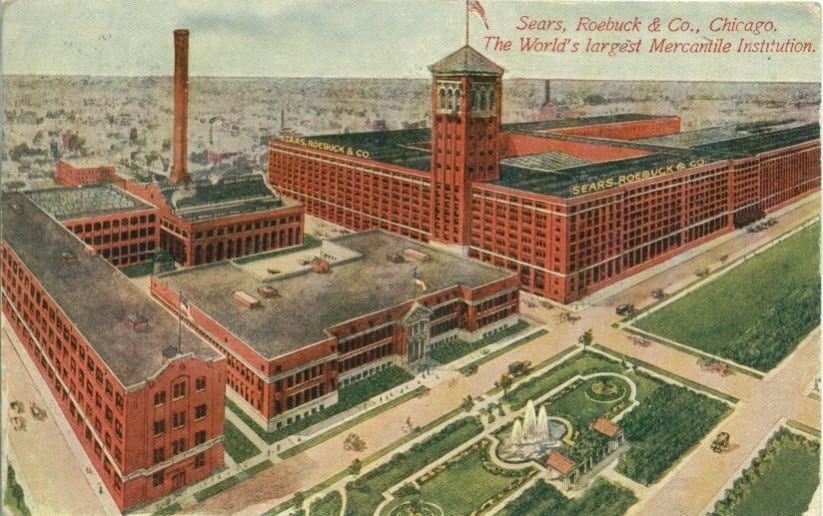

Under Rosenwald’s leadership, in 1906, Sears, Roebuck built a huge headquarters and catalog facility on the west side of Chicago. New methods of receiving and filling orders were pioneered by Rosenwald’s able management team. The right items got to the right customers—quickly. The new facilities also provided parks and entertainment facilities to make for a better working environment, rare for the era.

Sears roared ahead of Montgomery Ward, a company two decades older and the creator of the first big general merchandise mail-order catalog. Also in 1906, Goldman Sachs underwrote a public offering of Sears stock to help finance the company’s rapid growth, making Sears one of the first retail companies to “go public.”

In 1916, Rosenwald pursued his belief in “sharing the wealth,” setting up a profit-sharing and pension fund for Sears employees, contributing millions of dollars’ worth of Sears stock. Most business people considered this an unsound, expensive idea, but Rosenwald was a man of strong, independent convictions.

Rosenwald led Sears to revenues of $10 million in 1900, $50 million in 1907, and $235 million in 1920, a remarkable record by any means. Sales and profits slumped in the depression of 1921, and Rosenwald used his own personal funds to bail the company out. By the mid-1920s, the wealthy Rosenwald was ready to step down from leadership, spending more time on his philanthropic pursuits. (He went on to build over five thousand schools for poor African Americans in the South, create and fund Chicago’s pioneering Museum of Science and Industry, and lead many other charitable activities.)

[Marketing] “is the study of the needs and wants of the customer, and fulfilling those needs and wants with a superior product or service at the very lowest possible prices.”

Robert Wood Arrives at Sears, Roebuck

Given that his fellow corporate officers were also approaching retirement age, Rosenwald searched for a younger man to run the company, someone in his forties. He focused on the railroad industry, which was powerful at the time and full of executives with experience leading large numbers of workers, covering large territories, and managing “logistics.” He chose Charles Kittle, a vice president of the well-run Illinois Central Railroad. Soon after promising the job to Kittle, Rosenwald’s friend and shoe supplier, Wendell Endicott of upstate New York, told him that Robert Wood was also “on the market.” Perhaps realizing that Wood would be even better than Kittle, given Wood’s experience at Ward’s, Rosenwald offered Wood a vice presidency at Sears. As a man of his word, Rosenwald would not renege on his offer of the presidency to Kittle.

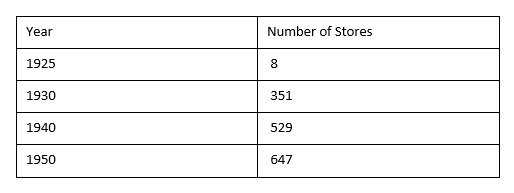

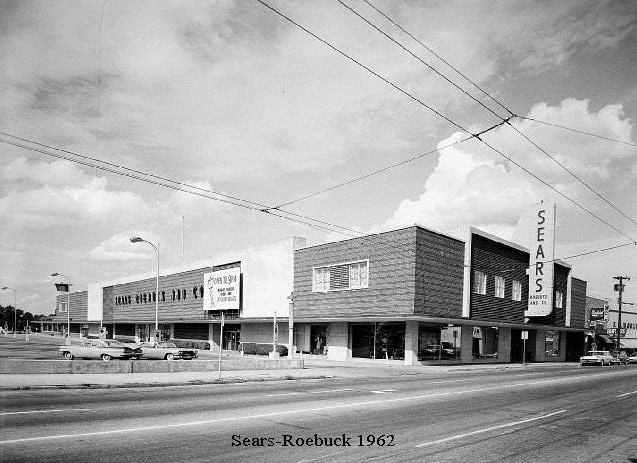

Wood was interested in the job, but only if Rosenwald and Kittle would let him try his idea of opening retail stores. While most sources indicate that Rosenwald was not crazy about the idea, he agreed, knowing Wood would be a great addition to the company. On November 1, 1924, both Kittle and Wood joined Sears. Wood was really setting the strategy for the company going forward. Just three months later, on February 2, 1925, Sears opened a test retail store on the first floor of the Chicago mail-order plant. By the end of 1925, seven more stores were opened as Wood tested his ideas. Six of the eight stores were in mail-order plants, one was a free-standing store in Chicago, and the eighth store was placed in a smaller city, Evansville, Indiana. Wood tracked the Evansville experiment closely, visiting the store frequently.

On January 2, 1928, the relatively young Charles Kittle died suddenly. After an agonizing (for Wood) week of thought by Rosenwald, he picked Wood to lead the company. General Wood became the president of Sears, Roebuck on January 11, 1928.

As the following paragraphs indicate, despite running a giant company, Wood was at heart an entrepreneur, always trying new ideas and experimenting. Today managers often talk of “reinventing” a big company, but they rarely do it successfully. Wood actually did it, in a company that was already highly successful and profitable.

Robert Wood and Retail Stores

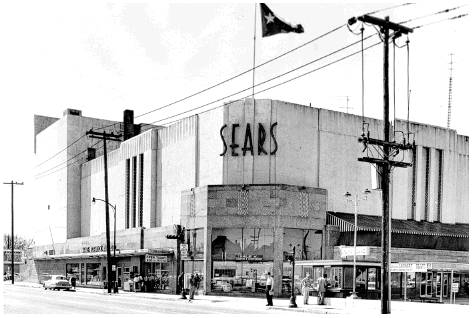

Finally in the driver’s seat, Wood pressed ahead full-steam on building retail stores across America. Leveraging Sears’s catalog plants—giant warehouses across the country—and Sears’s massive buying organization and supply chain, he wanted to deliver to the American customer the best values, whether in the catalog or in stores.

His strategy was based on his understanding of a population that owned automobiles. The older department stores like Macy’s and Marshall Field that had dominated urban retailing had huge facilities in the centers of cities, where the subways, elevated lines, streetcars, and buses came together. They had no parking. They sat on real estate that was the most valuable in each city.

Wood built his stores on cheaper land away from the old downtowns. He added parking. He carried large assortments of auto parts, tires, batteries, hardware, and other categories where Sears was strong. While the old department stores catered to women, he wanted his stores loved by the whole family, including men.

The stores began as bargain stores, with cheap fixtures and few amenities. Over time, Wood and the company learned that it was worth spending money on nicer, better-looking stores and adding customer services.

By 1932, the company had opened 374 new stores across the nation, and the revenues of those stores were greater than the revenues of Sears’s mail-order operations.

None of this growth came easy. It represented the transformation of a company that was already huge. Wood started with no executives experienced in operating retail stores. A believer in promotion-from-within, he struggled to develop and train people who could manage stores, a very different task from running a mail-order operation. He even tried to buy the J. C. Penney company to obtain retail experience and expertise, but Mr. Penney would not sell out.

Stresses developed between Sears’s traditional mail-order executives and those leading the stores. Wood, always great at arbitrating disputes within the organization, made everyone work together as a team. Many mistakes were made in every aspect of the stores, but the ever-adaptable, ever-learning Wood led the company to work out the problems. New store openings slowed in the Great Depression of the 1930s, actually giving the company some breathing room to work out its issues.

After World War II, Wood’s studies of government data led him to believe that the American economy would boom due to pent-up consumer demand after war-time shortages. Ward’s leadership believed the country would go into recession, as it had after previous wars. Sears built new stores as fast as possible, while Ward’s built none. Ward’s never recovered from this strategic mistake, despite efforts to save the company in the 1960s and 1970s by one of Wood’s proteges. Ward’s finally went bankrupt by 2001.

Sears, Roebuck Number of Stores

Above all else, Wood understood, respected—even loved—his customers. He made it clear to the entire organization that only the customer could fire them. Sears’s ultimate responsibility was to discover, develop, and sell to the public the best products at the lowest possible prices. Sears soon became the largest general merchandise retailer in the United States, surpassing companies which had been in retailing far longer.

“There are four parties to any business….the customer comes first….the employee comes next….then comes the community….last comes the stockholder….if the other three…are properly taken care of, the stockholder will benefit in the long pull.”

Robert Wood and Sears the Buyer of Merchandise

Taking ideas learned in Panama and in World War I, Wood made his huge buying force become experts in their fields. They were not only required to be good buyers, but they were to visit the factories, understand every step of production, and work closely with long-term suppliers to create products that served the customer.

Wood not only continued to work with the tire companies and buy rubber for them, but his organization went on to make massive investments in cotton, other textiles, and other ingredients for their suppliers, lowering the costs all along the supply chain. From time to time, Sears financed suppliers and sometimes owned substantial shares of their stock.

At the same time, he required his suppliers to be profitable. He was wary of any supplier who sold all their output to Sears, believing that having other customers kept the suppliers (and his buyers) on their toes and aware of trends.

A top priority was product innovation. Suppliers, Sears’s testing labs, and the expert buyers were always on the lookout for ways to offer a better product at the same price, the same product at a lower price, or sometimes even a higher-priced product which was far superior to what competitors offered. Higher capacity refrigerators resulted when the company found that the cost of a little more steel was small. Longer-lasting tires and batteries came along in time. Every department of the company worked to ensure that Sears sold items which the competitors couldn’t touch in ultimate value.

“I believe there is no limit to what can be accomplished by a force of employees who are given an opportunity for self-expression.”

Robert Wood and Sears’s Employees

Picking up on Rosenwald’s policies, Wood expanded the profit-sharing and pension plan, which invested in Sears’s stock. By the 1970s, employees owned over one-quarter of Sears’s stock through this plan. The plan was biased in favor of hourly employees and sales clerks, limiting the amount executives could make. For each dollar contributed out of employees’ paychecks, the company contributed another three to five dollars. As Sears grew in size and the price of the stock rose, many became millionaires and thousands had more-than-comfortable retirement nest eggs.

General Wood spent endless hours visiting the stores and mail-order plants, talking to everyone he met. He always had an open-door policy in his office. His secretary kept files on people from top executives down to salespeople, so that Wood could ask about their families when he met them, and know all their names. (He was said to have a photographic memory, especially for numbers and profit statements.)

Wood always believed in paying everyone rates that were higher than the going rates in retailing. He wanted his professional appliance salespeople to make a good living. He believed in promotion-from-within, and thousands rose through the ranks. Managers were especially promoted if they proved they could treat their people right, and most importantly, develop future managers. In its glory days, very few people ever left the employ of Sears, Roebuck.

“If our democracy is to survive, every businessman has to take his social responsibilities, his duties as a citizen more seriously.”

Robert Wood and the Community

Perhaps above all else, General Robert Wood believed in America and the American people. Highly unusual for corporate executives of the period, the lifelong Republican backed Franklin Delano Roosevelt for president in his first two elections, and supported many New Deal policies. Wood saw people struggling, and believed that extreme steps were required. He thought Sears could not succeed if the American people did not succeed.

Following in Julius Rosenwald’s footsteps, he saw the American South suffering, lagging behind the rest of the nation. The South was too dependent on agriculture, and most of that agriculture was cotton, with farmers dependent on one crop and its price swings. Under Wood, Sears set up thousands of programs with the 4-H and Future Farmers of America. Young farm kids were given chicks to raise—the best were then given a hog a year later, and after another year, a cow. The idea was that diversifying farm income would help these farmers. Sears copied these programs outside the South, across the United States. In further efforts to diversify the Southern economy, Wood’s buyers urged their suppliers to build new factories in the South.

Wood required his store managers to become movers and shakers in their local communities. Points for promotion were scored by leading the Chamber of Commerce, the YMCA, or other community efforts. Sears gave up substantial profits by holding cash deposits in local banks rather than pooling all the funds in the big New York and Chicago banks.

Wood’s ambition did not stop at the US border. He studied his demographic numbers and saw opportunities in Canada and Latin America. In Canada, he very successfully partnered with the department store chain Simpson’s to create Simpson-Sears. In Latin America, especially Mexico, he built Sears stores following his American policies. He hired and trained local managers, and helped build factories across Latin America, applying principles developed in the United States.

(Wood’s fundamentally entrepreneurial instincts also led him to create the enormously successful Allstate Insurance, against the advice of his board of directors.)

At every turn, Wood was asking, “How can we make our customers stronger, wealthier? How can we serve them better?”

The Overall Philosophy of Sears under Robert Wood

Today there is a movement called “Conscious Capitalism,” initiated in large part by the founder and chief executive officer of Whole Foods Market, John Mackey. A key idea is that corporations do best when they serve all their constituencies—customers, employees, suppliers, community, and stockholders. As indicated above, both Julius Rosenwald and Robert Wood were well ahead of the curve on these concepts. Each aspect of the company’s role in society has already been touched on except for the stockholders—were they left out?

Hardly. Robert Wood stepped down from Sears’s leadership at the age of seventy-five, in 1954, though he remained a very active board member and force in the company’s decisions until 1968. From 1924 to 1954, the thirty years in which Wood ran day-to-day operations, revenues rose from just over $200 million to almost $3 billion, almost three times the size of the next largest US non-food retailer, J. C. Penney. Profits grew from $14 million to $141 million. Employment surged from twenty-three thousand to two hundred thousand. Sears in this period became one of the most profitable retailers in the world, and the stock went up accordingly. In 1923, before Wood’s arrival, the company’s stock (market capitalization) was worth $386 million. When he stepped down from day-to-day management in 1954, it was worth almost $2 billion, and by 1969 $10 billion.

Robert Wood the Leader

Lessons for leaders abound in the Robert Wood story.

He was above all else, human—he loved meeting people and talking to them. He walked the stores and mail-order plants continually. He knew people’s names. He never liked military discipline, and never went through channels—every Sears employee knew they could talk directly to him. He was always on the lookout for good ideas, no matter who had them. At one point in his numerous managerial experiments, over four hundred store managers reported directly to him, with no layers of management to interfere!

Wood wanted to place as much power close to the customers as possible—out in the stores, not at the headquarters. He continually harped on his executives to let their people alone. He instructed them to give guidance, to set an example, but rarely to give orders. He believed that hiring good people was the key. Then give them responsibility and let them prove themselves. The characteristics he most valued were “character and integrity.”

He especially believed in making mistakes. Only by making mistakes would people learn, and he often let his people do things he “knew would not work,” believing that the lessons learned would be worth the profits lost.

Always a bold thinker, near the end of his reign Wood proposed that Sears be split up into smaller, regional companies. He had studied the 1911 breakup of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust, which resulted in several smaller companies that became worth more than the old company. His idea of smaller, leaner companies was never carried out, however.

Wood was revered for his objectivity. He fired people whom he really liked, and promoted people he disliked, based solely on how well they did their jobs. When he called someone on the carpet, they almost always came out feeling better, because he also complimented them on the things they did right.

For many years after he retired, the stores were still filled with his picture and with stories told by employees of “The time I talked to the General.” This level of engagement can be hard to develop even in small organizations, let alone huge ones like Sears.

“Our whole future depends on the proper selection, proper reward, and proper elimination of personnel.”

Robert Wood the Public Figure; Controversy

As the leader of one of the nation’s largest and most important companies, Wood was always very visible. He made frequent, articulate speeches, and never held back on his opinions. Some of his friends suggested he run for president in 1940, an idea Wood quickly dismissed. Over his life, his convictions gave rise to some controversy. As during his support for FDR and the New Deal, Wood never backed away from that controversy.

As World War II approached, Wood chaired the America First Committee, which opposed going to war. Based on his life experience, Wood felt that Europe was mired in its own complex past, and was not looking forward. He feared American involvement in the war would not be good for America and not do much to improve things in Europe.

America First attracted a broad group of people. Some like Wood’s friend Charles Lindbergh were openly pro-Germany, often with an anti-Semitic subtext. Despite pressure to do so, Wood never disavowed Lindbergh, and refused to step down from leadership of America First. When the US entered the war, he immediately disbanded America First and Sears got behind the US war effort. Wood later said that the reason he did not quit America First is that he feared some in the organization would continue to oppose the war once it started, and he wanted to make sure that did not happen.

Nevertheless, Wood got a reputation of being an isolationist and anti-Semitic. However, a close review of his relationship with Julius Rosenwald and Rosenwald’s son and large Sears stockholder, Lessing Rosenwald, indicates that Wood could get along with anyone. In the 1920s, Wood played weekly bridge with Rosenwald’s Jewish leadership team at Chicago’s Jewish club. And Wood made numerous speeches declaring the importance of faith, whether Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish.

Robert Wood the Man

Robert Wood was undoubtedly “a piece of work,” a character. He seemed to have no desire to follow norms or act “as expected.” Psychologists might say he was self-actualized.

Wood was clearly a man in a hurry. He often carpooled with other executives or even clerks. When he drove, he frightened all of them. He would race the forty-minute drive from his home north of Chicago to the west side headquarters, often trying to beat other executives following the same route.

Meetings with Wood were scheduled in fifteen-minute intervals, with few exceptions. If you didn’t leave at the end of your time, he’d stand up and face the window, or even walk out of his own office. Due to his quick mind, a lot could be covered in fifteen minutes.

The general had no use for appearances. He began this tradition at West Point, earning those demerits. Even as the chief of one of the nation’s largest companies, his socks did not always match, his suit jacket did not always match the pants, his zipper was sometimes undone, and his clothes were often covered with cigarette tobacco and ash flicks.

A lifelong smoker, like many in his era, Wood’s wife and doctor together finally convinced him to quit. The only thing that worked was to supply him with plastic cigarettes, complete with fake stained ends. Wood would chew on these all day. He also loved caramels, but often ate them so fast that he did not bother to take off the paper wrappers before consuming them.

As much as Wood genuinely loved people, he also loved data and numbers. He read everything from history to profit-and-loss statements, which he memorized to the decimal point, store by store, product line by product line.

A lifelong learner, he was still taking golf lessons as he approached ninety years of age. While few would call the General perfect, almost all who met him called him a genius.

Even with all his civic engagements and tireless efforts at Sears, he was an ardent family man and usually home for dinner. When he died on November 6, 1969, at the age of ninety, he left behind five children, fifteen grandchildren, and thirty-six great-grandchildren. His wife’s statement that, “Rob was a man of great vigor” is one of the greatest understatements made about this man who led a full life while contributing to the lives of millions of others.

Lessons from Robert Wood

Today Sears struggles—more on that below. Amazon is gradually moving from being a pure “mail-order” company (using the updated technology of the Internet) to buying Whole Foods Market and opening book and other stores of its own. Walmart, the world’s largest company, faces new challenges after also being led by a lover of people, master strategist, and “logistician,” Sam Walton. How much could these leaders and others in the retail industry learn from General Wood? A deeper dive into the sources for this story, listed below, might pay huge dividends.

Companies in every industry, well beyond retailing, struggle with developing, enhancing, and maintaining their “corporate culture.” Many leaders are disconnected from their own employees. Often big corporations give only lip service to putting the customer first or contributing to society and the communities in which they operate. Might they also learn from the General?

Robert Wood and his policies had an enormous impact on millions of lives: his employees, suppliers, stockholders, customers, competitors, students of management practice, farmers across America, residents of the South, the people of Latin America and Canada, people in every town and city Sears operated in—the list goes on. He helped build the Panama Canal and win World War I. Will Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, or Elon Musk have that kind of impact on that many people over so many years? Only time will tell.

“The customer is our real employer. The moment we lose his confidence, that moment marks the beginning of the disintegration of this company.”

The Sears Epilogue

It will not be news to the reader that Sears is today in severe decline. In October, 2018, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. For those of us who study and love retailing, this is the saddest of stories.

The history of this decline is complex, with many factors and players involved. While the brilliant management thinker Peter Drucker still considered Sears one of America’s greatest companies in the 1970s, by that time top Wall Street analysts and other observers were already seeing “chinks in the armor.”

Robert Wood was a master strategist. But after his leadership, the company made many strategic mistakes.

Sears once held dominant positions in such categories as auto parts and hardware. Since the 1970s, these categories boomed, giving rise to the still-successful Home Depot, Lowe’s, AutoZone, O’Reilly, and Advance Auto Parts. Even the appliance category, once ruled by Sears, has found new life at Best Buy, Home Depot, Lowe’s, and others. In these fields, Sears failed to protect its retail fortress (or defend its “moat”).

“The bigger they are the harder they fall.”

Richard Sears’s first mail-order catalog was published in 1887. Sears’s management shut down the catalog operation in 1993. The following year, Jeff Bezos founded what was to become Amazon, in large part following in Julius Rosenwald’s footsteps. While few businesspeople of the time foresaw the impact of the Internet, there is a reasonable chance that the ever-curious, forward-looking Wood might have been one of them had he still been alive.

Management mistakes have been just as persistent at Sears.

After Wood stepped down, the company had six leaders averaging four years each, compared with three leaders in its entire history up to that point (excluding the short-lived Charles Kittle). The board, heavy with inside executives, promoted men who were nearing retirement. Perhaps Wood had failed to develop independent thinkers, as often happens with brilliant chiefs. Perhaps the policy of promoting from within haunted the company, which failed to bring in new blood.

Those ”leaders” proudly built the world’s then-tallest building, the Sears Tower, which did little for customers, employees, or stockholders. Infighting in the formerly collegial Sears atmosphere broke out.

For a while, Sears tried to expand into fashion categories, promoting “the Softer Side of Sears.” By the early 2000s, hedge fund “genius” Eddie Lampert got control of the company, merging it with his other holding, Kmart, into a new company, Sears Holdings. Lampert, perhaps the opposite of Wood, reportedly runs the company by telephone from his Connecticut home, and rarely if ever visits the Chicago headquarters.

After peaking at $144 per share in 2007, Sears Holdings’ stock traded at 40 cents prior to the bankruptcy filing. The total value of Sears’s stock (market capitalization) is under $50 million, a fraction of what the company was worth when General Wood arrived on the scene.

(Sears Canada is already gone; by contrast, Sears Mexico was sold to billionaire Carlos Slim’s Grupo Carso and is well-run and prospering.)

While it might be too late to save the Sears company, it is never too late to study and learn from the lives and ideals of America’s great entrepreneurial and business leaders, men like Robert Wood and women like Estee Lauder. That is why we continue to produce these profiles of “American Originals.”

____________________________________________________________________________________

Sources:

This article is in large part based on the outstanding book Shaping an American Institution: Robert E. Wood and Sears, Roebuck, by James C. Worthy (1984), a longtime Sears executive and later business professor. More has been written about Sears than any other American retailer. The May 1938 issue of Fortune Magazine contains a fascinating profile of Wood and Sears while they were converting the company to a retail chain. The definitive and excellent history of Sears up through the late 1940s is Catalogues and Counters: A History of Sears, Roebuck and Company (1950), by Boris Emmet and John E. Jeuck. A chatty “tell-all” about Sears after Wood is The Big Store: Inside the Crisis and Revolution at Sears (1987) by Donald R. Katz. Another volume filled with interesting facts and anecdotes is The First Hundred Years Are the Toughest: What We Can Learn from the Century of Competition between Sears and Wards (1988), by Cecil C. Hoge. Many additional books can be found on Amazon or other bookselling websites about Sears and particularly Julius Rosenwald. Much is written online on retail and investment websites about Sears today, though no one has yet written a book covering the full arc of the company’s history—perhaps it is best for writers to wait a few years to see how things turn out with Mr. Lampert.