On February 11, 1898, John Charles Smith of Toronto hit his head and died of a cerebral hemorrhage. The Irishman left behind his wife, Charlotte; five-year-old daughter, Gladys; another daughter, Lottie; and a son Jack. Destitute, Charlotte struggled to keep her family together. Eldest child Gladys (born April 8, 1892), soon to be renamed Mary Pickford, became the most famous woman in the world—star of stage and screen and co-founder of United Artists, one of the best-known companies in Hollywood. This is her story: a story of fame, fortune, romance, and human tragedy.

Beginnings

To make ends meet, Charlotte Smith quickly took in boarders after her husband’s death. The master bedroom was rented to a series of single women. Then Charlotte took a chance on a man, a Mr. Murphy. It was considered risky to have a man in the house at the time, though Murphy was married. Worse yet, Murphy worked in the theater as a stage manager, viewed as one of the lowest rungs of society. “Show folk” were considered lowlifes, serving rowdy audiences who often threw things at the actors on stage.

Charlotte was therefore shocked when Murphy asked if the girls might join the cast of a play he was stage-managing, The Silver King. The indignant Charlotte replied, “I’m sorry, but I would never allow my innocent babies to associate with actresses who smoke … the thought of those infants making a spectacle of themselves on a public stage!”

But Murphy convinced her to come to a show and meet the cast, who he said were good and bad people just like anyone else. He also offered eight dollars a week for Gladys, and a little less for her sister. Charlotte, who needed the money, met the cast, who were on their best behavior.

On January 8, 1900, seven-year-old Gladys made her first appearance on stage, playing two secondary roles in The Silver King, as both a boy and a girl. (In those days, it was common for girls to play boys in plays, and occasionally boys played girls.) She was immediately at home on the stage and enjoying the limelight. One thing led to the next, and on April 9 of that year, the day after she turned eight, Gladys Smith was in a play called The Littlest Girl.

Then, in another production of The Silver King, Gladys said she did not want to play the secondary roles, she wanted to play a leading role. Her mother hesitated, pointing out that Gladys had had no schooling, and could not read; there was no way she could memorize the plentiful lines required of a lead character. But the diminutive Gladys persisted, and spent hours learning her lines. By April of 1901, nine-year-old Gladys was playing the plum role of Little Eva in the ever-popular Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

This was the era of Vaudeville and of the touring company. At the dawn of the twentieth century, more than twenty thousand actors and three hundred touring troupes spread out across the United States. By the autumn of 1901, the Smith family had joined them. Gladys got the best roles, but sister, Lottie, and brother, Jack, were often in the shows, and even Charlotte occasionally acted as an Irish maid or other stereotyped character. Life was difficult, playing to rough audiences in tawdry theaters, jumping on the night train as soon as a show ended, arriving in the next town just before it started, sleeping sitting up on the trains or in the worst hotels in town. Year after year. Gladys later said that she learned to read from looking at the passing billboards. She had spent, at most, three months in formal schooling. She liked being on stage, but the restless life was little fun. The family would split up, touring with different shows, and sometimes little Gladys travelled alone, without her mother and siblings. There was no time for play, no time for being a child. Gladys also watched the older actresses, saying, “My heart was filled with pity for them and dread for myself. They were fading so fast. Life had trampled them …. Day by day their eyes became more dulled and hopeless. Yesterday they had been leading women. Today they were abject supplicants of the theater. Tomorrow, oblivion.” As an alternative to this fate, she dreamed of becoming a seamstress, of having her own business, “Dresses by Gladys.”

Touring companies worked through the winter season. Most of the Smith family spent their summers in Toronto, but one summer Gladys was living with friends in New York. The bright lights of Broadway— “the big time” in the theater— attracted her. Gladys admired the work of successful actresses. She peered into their fabulous individual dressing rooms, with a star pasted on the door, and compared them to her rugged, shared backstage accommodations. She admired the trappings of their success. When a passing limousine splashed her skirt with slush, she told her friend, “Never mind, we’re going to have a car nicer even than that, and very soon, too.” She set her sights on meeting legendary theatrical producer and director David Belasco, known as “The Bishop of Broadway.” Gladys dreamed about how she would wait outside his office for hours, or catch him leaving the theater, how he would “discover” her.

Gladys pleaded with the maid of prominent actress Blanche Bates to help her reach Belasco. The maid took a liking to her, and returned from Bates’s dressing room, saying, “She said to go see Mr. Belasco and say that Blanche Bates sent you, but she does not want to hear any more of it.”

At Belasco’s office, the well-trained office boy resisted all of Gladys’s entreaties and arguments. Gladys grew louder. Belasco’s associate William Dean opened his office door and asked what the trouble was. Gladys rushed into his office, spouting, “My life depends on seeing Mr. Belasco!” Dean was impressed, and a few weeks later Mary was invited to meet Belasco following the performance of one of his plays.

When Belasco asked her name, Gladys replied, “At home in Toronto, I’m Gladys Smith; but on the road I’m Gladys Milbourne Smith (a name dreamed up for one of her performances).”

Belasco replied, “We’ll have to find another name for you. What are some of the other names in your family?”

Gladys answered, “Key, Bolton, De Beaumont, Kirby, Pickford.”

“Pickford it is. Is Gladys your only name? Haven’t you another?” asked Belasco.

“I was baptized Gladys Marie,” said the girl.

“Well, my little friend, from now on your name will be Mary Pickford,” answered the great man. He asked Gladys, now Mary, to come back the following night and see one of his plays, and to be ready to give him a sample of her acting.

Belasco also asked, “By the way, what made you say your life depended on seeing me?”

The ever-ambitious Mary responded, “Well, you see, Mr. Belasco, I’m thirteen years old (a lie), and I think I’m at the crossroads of my life. I’ve got to make good between now and the time I’m twenty, and I have only seven years (another lie) to do it in. Besides, I am the father of my family.”

“Why me?” asked Belasco.

After six years of crisscrossing the country, Mary understood the egos of the theater world. The street-savvy Mary answered, “Mother always says I should aim high or not at all.”

The next night, fifteen-year-old Mary gave Belasco a brief performance, of which she was highly self-critical (a trait that stayed with her for life). Belasco said, “So you want to be an actress, little girl?”

Mary: “No sir, I have been an actress. I want to be a good actress now.” On December 3, 1907, Mary Pickford opened as Betty Warren in William C. DeMille’s play The Warrens of Virginia at Broadway’s Belasco Theater. Mary was in awe of the beauty of the theater and the wealth and attire of the audience, who had paid the great sum of two dollars each to see the play. Each week, she sent twenty dollars of her twenty-five-dollar a week paycheck home to Charlotte, living on the remaining five dollars. Frugality and saving were another habit that Mary Pickford maintained throughout her life. Mary’s pay rose to thirty dollars in the summer of 1908 when The Warrens of Virginia closed on Broadway and began a tour of the United States and Canada. Mary received great publicity in her hometown of Toronto. By March of 1909, the Smith family had saved up two hundred and fifty dollars.

Mary Pickford Risks Playing in the Movies

Though eager to play more roles for Belasco, Mary’s future was uncertain. She was “jittery, anxious.” She even entertained the notion of doing something “loathsome, cheap, and despised,” acting for “motion pictures.” The movie industry had begun with one-reel peep shows and evolved to nickelodeons, where for a nickel anyone could watch a chase scene or something more lurid. (Broadway theater was for the rich who could afford two dollars.) Inventor Thomas Edison and a handful of “studios” were cranking out one-reel films, lasting only a few minutes. By 1907, American had ten thousand nickelodeons, selling two million tickets a day. This was the entertainment of the poor, of immigrants, not anything respectable. Few Broadway performers would even consider such a thing, a “fall from grace.” But it was reputedly “an easy five dollars a day.”

Mother Charlotte first mentioned the idea to Mary.

“Oh no, not that, Mama,” cried Mary.

“Well, now, it’s not what I would want for you, either, dear. I thought if you could make enough money, we could keep the family together.” Always loyal to her mother and her family, Mary agreed. Though, dressed up in her Easter finest and high heels on the way to the Biograph movie studio, she still said to herself, “How could Mama ask me to do this? How could she ask me, a Belasco actress!”

At Biograph, the most highly respected company of the day (which is not saying much), Mary met and began working with silent film pioneering director David Wark (“DW”) Griffith. Biograph cranked out two to three short films a week from its studio in a brownstone in Manhattan. Many stage performers were not able to convert to film: acting for a live audience was entirely different from acting for the camera, including close-up shots. Griffith pointed out that “it was all about the eyes.”

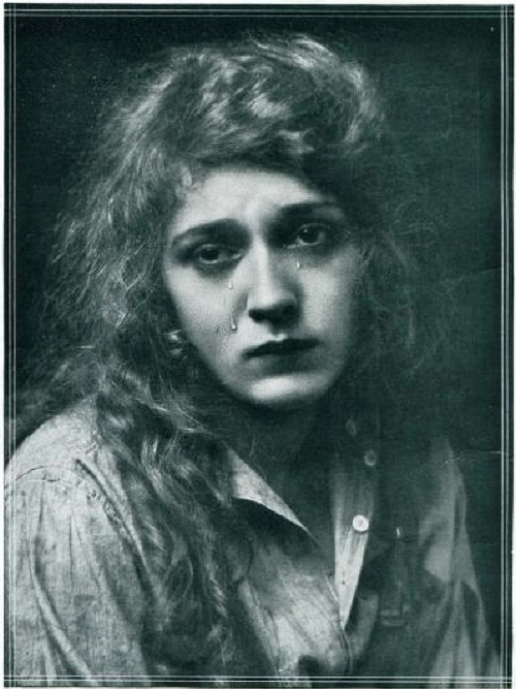

Mary worked hard and perfected the burgeoning “art.” In 1909, the seventeen-year-old Mary played forty-five roles for him, and in 1910 thirty-five. Her multi-emotional face and curly hair showed up as a child over and over, often petulant and rebellious. She also became an astute student of editing, lighting, and camerawork, observing and asking questions.

Mary also started writing scenarios for films, selling them to Biograph and its competitors for fifteen to twenty dollars each. Her weekly pay rose to a hundred dollars. She continued to save money. When another actress bought a fancy feathered hat, Mary responded, “You’ll regret anything so silly. You’ll have that worn-out bird of paradise hat, and I’ll have property.”

In 1910, after filming in California, the emerging center for moviemaking, Mary and her sister, Lottie, returned to New York with twelve hundred dollars, which Mary promptly changed into fifty-dollar bills. Presenting them to her mother, Charlotte thought it was fake “stage money,” never having seen a fifty-dollar bill. In December 1910, Mary was lured away from Biograph by pioneer film-maker Carl Laemmle, who later founded Universal Studios, with a salary of $175 per week (about $5,000 in today’s money).

Without telling her mother, Mary, not yet nineteen, married fellow actor Owen Moore on January 7, 1911. But her mind was on her work, Owen drank too much, and the marriage was not a happy one. Mary’s pay eclipsed Owen’s seventy-five dollars a week. Owen grew moody and abusive, and the two were often far apart, Mary filming as far away as Cuba, often returning to live with her beloved family.

Mary moved from studio to studio, her income rising to $225 per week. Yet she was not happy with the people she worked with. While her relationship with DW Griffith was always turbulent, she knew that he got the best acting out of her, so in 1912 she took a cut to $175 to return to DW’s orbit.

Playwright William DeMille (the elder brother of Cecil, later a famous film-maker), in a letter to David Belasco, wrote: “Do you remember that little girl, Mary Pickford, who played Betty in The Warrens of Virginia? I met her again a few weeks ago and the poor kid is actually thinking of taking up moving pictures seriously …. That appealing personality of hers would go a long way in the theater, and now she’s throwing her whole career in the ash-can and burying herself in a cheap form of amusement which hasn’t a single point that I can see to recommend it. There will never be any real money in those galloping tintypes and certainly no one can expect them to develop into anything which could, by the wildest stretch of the imagination, be called art.”

Though now a modest star in the movies, Mary thought of returning to the more prestigious stage. When she mentioned this to DW Griffith, he replied, “Do you suppose for one moment that any self-respecting theatrical producer will take you now after spending three years in motion pictures?”

Mary’s Broadway friend Mary Gish said, “The poor girl must be very poor indeed to have so degraded herself.”

Yet soon, Gish’s daughters, Lillian and Dorothy, were making films, too. Lillian Gish became a star and a lifelong friend of Mary’s.

Her Star Rises and Rises

By 1912, Mary was a superstar, “The Queen of the Movies.” Her ability to twist her face, to turn from ruffian to romantic to comic, to express every emotion with her eyes, captivated audiences. Yet Mary still had a thirst for the stage and returned to David Belasco on Broadway (at $200 a week), finally getting her luxurious dressing room with a star on the door.

Despite her newfound success on Broadway, Mary continued making moves and following the evolution of the embryonic industry. One day she read a newspaper article about Adolph Zukor, a producer who was changing the industry, driving it toward making longer films with more character development and stronger plot lines. He even dreamed of taking Broadway plays and putting them “on celluloid.” His concept was “Famous Players in Famous Plays.” Edison and the filmmakers resisted such ideas, since they were making plenty of money cranking out five- and ten-minute films. (For Zukor’s impressive story, see this article.)

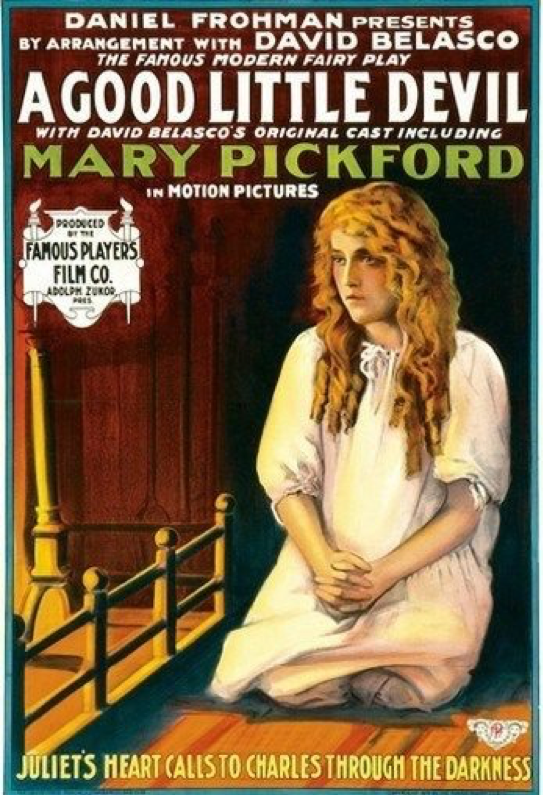

Zukor saw Mary’s success for Belasco and made a film of his play A Good Little Devil, starring Mary. Zukor was impressed with her performance and set up a lunch with Mary and her ever-present “business manager,” mother Charlotte. Zukor wanted Mary in his movies, but Mary pushed back that she loved the stage and working for David Belasco.

“What salary would you consider paying Mary?” asked Charlotte.

Zukor vaguely answered, “A few hundred dollars a week.”

DW Griffith soon countered with three hundred dollars a week for his films, but Zukor won out with the fabulous amount of five hundred dollars a week. This income matched what a typical American worker made in a year, about $13,000 in today’s money.

Despite her prior successes, Mary’s first three films for Zukor’s Famous Players company catapulted her to a new level in the public’s eye. In the Bishop’s Carriage came out in 1913, Caprice the same year, and Hearts Adrift the following year. These films cemented Mary’s image in the minds of movie-goers: “Half savage, half angel, dressed in tatters, untamable, pugnacious, street-smart.” Mary’s character usually ended up with her virtue winning out, with happy endings as she found a rich love or other hero.

These days, it is easy to think of silent movies only as primitive, somehow incomplete precursors of sound film (“the talkies”). Yet silent films were a different art form, accessible to all, no matter where you came from or what language you spoke. They worked easily in any foreign market. Just as old radio dramas make the listener work to envision the scene, silent movies made the viewer work to imagine the sounds. Unlike the talkies, viewers could not turn away from the screen without missing something: every image, every smile, every frown carried meaning. The process of making the films was also very different from talkies. Since no sound was recorded, directors would scream at the actors to make them cry and tell them jokes to make them laugh, all while the cameras were rolling. After talkies, sound stages went quiet while shooting. Twenty-two-year-old Mary Pickford became a master of the art of silent film.

Adolph Zukor paid Mary one hundred dollars for her scenario for Hearts Adrift, released in 1914. The twenty-two-year-old actress played twelve-year-old Nina, a “wild child” and sole survivor of a shipwreck who then falls in love and becomes a “child-woman.”

Critics raved about her work, writing such florid prose as, “I am the delicate Feminism of Picturedom. The art seems to have culminated in me— in my diffidence and in my unassuming, reposeful manner.” Audiences spoke of her “weird, magnetic grip.” They wrote fan letters about her “big, round tender eyes.” “She gives one the impression of being honest, incapable of saying anything she does not feel, or of any affectation.” Mary Pickford was believed to be “the best-known woman who has ever lived, the woman who was known to more people and loved by more people than any other woman that has been in all history.” She became known as America’s Sweetheart, a moniker that stayed with her until the day she died.

Even Zukor, who went on to build the Paramount Pictures and theater empire, later remembered this era: “I was only an apprentice then, she was an expert workman.” When a competitor offered Mary two thousand dollars a week, Zukor countered with a raise to one thousand, which Mary accepted in order to keep working with her “Papa Zukor.” Mary and Charlotte made for a tough pair when it came to contract bargaining. By 1915, her pay again doubled, and twenty-three-year-old Mary also started receiving half the profits of her movies, unusual at the time.

As a star, Mary knew and befriended the other top film performers. Among them, she met Charlie Chaplin, a difficult man whom she never liked, but nevertheless she later became his partner in business. At the time she met him, Chaplin was at the top of the industry, making $10,000 a week plus a $150,000 bonus for just twelve films a year (bringing his total annual compensation to $650,000, equal to $17 million today). Thirty Manhattan theaters had contests for Chaplin imitators.

Chaplin’s movies were made by the Mutual studio, which offered Mary $1 million a year in 1916. Adolph Zukor countered with half the profits of her films, a $300,000 bonus, her own production unit with more creative control, and a guaranteed minimum of $500,000 a year, an offer she accepted.

Charlie Chaplin later said of her, “I was astonished at the legal and business acumen of Mary. She knew all the nomenclature: the amortizations and the deferred stocks …. all the articles of incorporation.” He (like most men of the era) found these gifts unseemly in a woman, especially a blond of small stature, “child-like.” He called her the “Bank of America’s Sweetheart.”

Mary Pickford was now twenty-four years old, a veteran of sixteen years in show business, a tireless worker, and (alongside mother Charlotte) one of the industry’s savviest contract negotiators. (Charlotte reportedly spent so much time clipping payment coupons off her bonds in a bank vault that her fingers got blisters.)

In 1917, two of Mary’s most successful films, Poor Little Rich Girl and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, premiered. Each film required new emotions, new faces. Some believe her finest work was in 1918’s Stella Maris, in which she plays two roles, a beautiful invalid girl and a “misshapen” orphan.

The Great Romance, Family Challenges, and More Success for Mary

Mary put on a good face about her marriage, clowning with Owen Moore for the press. But in no real sense were they a couple. In 1915, en route to a party, they had run into handsome Douglas Fairbanks and his wife in their flashy Stutz Bearcat automobile. Nine years older than Mary, Fairbanks had been a Broadway star who transitioned to the movies, in 1916 joining Adolph Zukor’s company. He was known for his athleticism: on film, instead of climbing stairs, Fairbanks would vault to the top of them. Even off-screen, he would jump into his open cars, not opening the door but jumping over it. He even did a handstand on the rim of the Grand Canyon. Mary Pickford was soon attracted to Douglas Fairbanks.

At the same time, Charlotte and Mary tried to hold their family together, but it was not easy. While Jack acted in over forty movies in his career, he began drinking heavily, which was also an issue for Charlotte and possibly her late husband. Lottie, on the other hand, was only in eight films, and was even more heavily into alcohol and drugs. Mary helped them out financially when possible and tried to get them jobs. Both her siblings began a series of unsuccessful marriages, Lottie giving birth to Mary Pickford Rupp, who ultimately used the name Gwynne and was raised at first by Charlotte and later by Mary.

Mary began spending more time with Doug Fairbanks and his friend Charlie Chaplin. While she never could warm up to the left-wing, semi-intellectual Chaplin, the three were visible around Hollywood and readily clowned for magazine photographs.

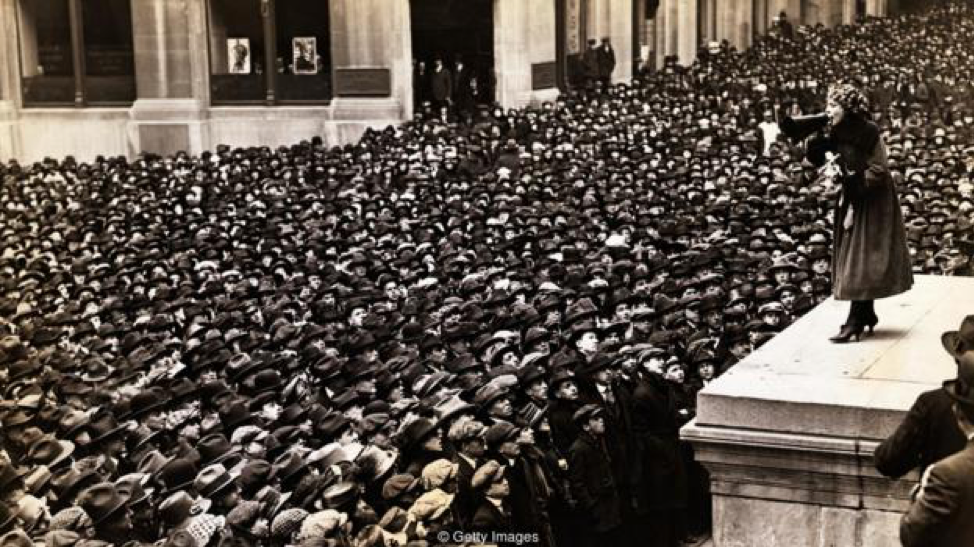

Mary’s fame continued to build. Renowned people from around the world sought (and received) audiences with her, including Sherlock Holmes author Arthur Conan Doyle, ballerina Anna Pavlova, and novelists Leo Tolstoy and H. G. Wells. Contrasting with Charlie Chaplin’s leftist politics, Mary was quite conservative. At first neutral toward the war in Europe, she and the film industry were soon caught up in “war fever.” She loved soldiers and threw herself into the war effort, with such phrases as, “Don’t you come back until you have taken the germ out of Germany.” She was photographed kissing the flag. In one parade in Washington, she was instrumental in raising $3 million in one day. In Chicago, where one of her famous curls was auctioned off for $15,000, she raised a million in one hour. The army named two cannons after her. And, in 1918, Mary paid $277,000 in the new income tax; both she and Fairbanks were among the largest personal taxpayers in America.

In 1918, upstart studio First National offered Mary $675,000 for just three pictures, plus half the profits and total creative control. Zukor countered with an unusual offer—$750,000 a year for five years, with the stipulation that she not make movies for any studio. This didn’t interest her because she lived for her work. But when Mary tried to get Zukor to beat the First National offer, he said he could not, it was just too much money. Mary and Adolph Zukor then parted ways professionally but remained friends for life. Mary and First National soon parted ways, but before they did, she made Daddy Long-Legs for them, a big hit and the first film over which Mary had complete creative control.

Also, in 1918, an unsuspecting Beth Fairbanks came to realize that her husband Doug had not been faithful and sued for divorce. She received a settlement of $500,000 and went on with her life, including raising Doug’s son Douglas Fairbanks Jr. (whom everyone called “Jayar” for Jr.). Amazingly, Beth always spoke highly of Mary and at times befriended her.

In 1921, Mary led in the creation of the Motion Picture Relief Fund to help down-and-out members of the film community, the first of many charitable efforts on her part.

Meanwhile, Jack was in the Navy, where he helped wealthy sailors pay to avoid dangerous assignments, resulting in his dishonorable discharge from the service. Ever protective of her clan, mama Charlotte got a judge to expunge the word “dishonorable.”

Changing the Industry

At the same time all that was happening, the film industry was continuing to evolve. The studios like Famous Players used a system called “block booking.” Under this system, every movie theater had to take a package of films from the studio, including both hits and losers. Mary and other stars realized that the studios were using their successful movies to carry the losers and objected to the practice. They also tired of working under tough contracts, usually with little control over who directed or the ultimate quality of each film.

Out of this situation arose the idea of a studio that would be owned and run by actors and directors, a studio that would sell each film on its own merits, without block booking. The “talent” would make a greater share of the profits and have more creative control. On January 15, 1919, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, DW Griffith, and western star William S. Hart (the “big five” of Hollywood) announced their intention to create United Artists to pursue such a strategy.

United Artists would not own a physical studio or theaters but would back and distribute the films of independent artists, including the founders. (Pickford and Fairbanks separately owned a studio lot which provided substantial cash flow to them.) William Hart was lured away by Zukor and dropped out, but the other four moved ahead with their plans, each an equal owner of United Artists. Charlotte represented Mary on the board of directors. Few thought actors could run a movie business: “The lunatics have taken charge of the asylum,” declared the head of a competing studio. DW Griffith, known for his blockbuster hits Birth of a Nation and Intolerance, soon seemed to prove the naysayers wrong; his 1919 Broken Blossoms was United Artists’ first hit.

More of Everything: The Heights

Mary and Doug continued their romance while churning out new movies. Doug begged her to marry him, but she hesitated, believing that a divorce from Owen Moore would ruin the purity of her reputation. Nevertheless, on March 2, 1920, Mary and Owen divorced in Nevada. At the time, she told the press she would never remarry. But twenty-six days later, Mary Pickford (age 27) married Douglas Fairbanks (age 36). At first the press was in an uproar, but by summer the public loved them. Their fame as a couple went on to exceed anything we witness in today’s celebrity couplings.

Before heading off to their “relaxing honeymoon” in Europe, Doug did a handstand on the roof of their New York hotel. Arriving in Europe, no relaxation was to be found. As their ship approached Southampton in England, airplanes dropped tiny parachutes on them, each carrying bags of letters or garlands of roses. The mayor greeted them, with a scroll signed by four thousand fans.

In London, the traffic jam stretched for miles in each direction around their hotel (The Ritz); King George V’s limousine was held up for twenty minutes. Crowds surrounded them day and night. As always, they played to the crowd, appearing on their hotel balcony, Doug doing his usual acrobatics. When they attended the theater, Doug gave a speech before the play, eliciting a standing ovation for ten minutes.

While Doug loved the attention, Mary was terrified. The public never knew that, as she was always kind and gracious, ideals pounded into her by Charlotte. When crowds tried to pull Mary from their open top Rolls Royce, Doug grabbed her and put her on his shoulders. There were more crowds in Paris, where Mary was almost trampled before being rescued. There was no time for relaxation and little sightseeing, though the couple did meet the royal and famous everywhere they went. The cult of celebrity had taken hold.

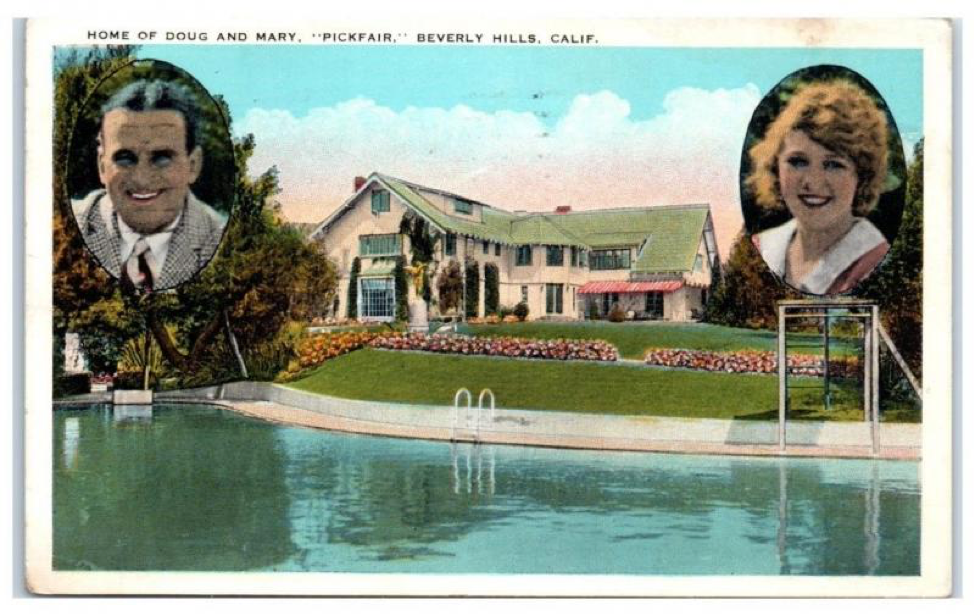

Upon their return to America, Doug and Mary immediately began building their dream home at Doug’s hilltop property which overlooked Benedict Canyon and the Pacific Ocean. Named Pickfair, the eighteen-acre property included an oyster-shaped swimming pool with its own sandy beach, kennels, a tennis court, and housing for the fifteen servants. People called it “the second White House.” This was the home of American royalty, the site of continual parties and dinners. Visitors included Albert Einstein, Amelia Earhart, Helen Keller, Jack Dempsey, the Kings of Spain and Siam, and the Prince of Sweden.

But Doug would also bring home whoever he found interesting—one evening, dinner was served to a wrestler, a “tramp,” a dwarf, and two homeless cats. Fairbanks was also a lifelong prankster; dripping goblets and rubber forks were not unusual. He even had a chair that greeted its occupant with a mild shock. Doug would play dog, run under the dinner table, bark, and nip at the guests’ legs. He might follow dinner by running through the steep hills on the property or going for a swim, urging his guests to follow along. (In a twist that was odd for Hollywood, Douglas Fairbanks was a complete teetotaler almost his entire life, and limited drinking at the house.)

For the next eight years, Doug and Mary spent every night together. If they were filming far apart in Southern California, Mary would have her star trailer pulled to Doug’s location each evening, to return to her set at sunrise. Mary would only dance with Doug, even resisting the charms of the Duke of York, the future King George VI.

Mary and Doug showered each other with gifts: she gave him fifteen paintings by western artist Frederic Remington; he gave her a 102-piece gold and porcelain tea set that had been a gift from Napoleon to Josephine. Mary loved gowns and jewelry and thought nothing of wearing thousands of dollars’ worth of rubies.

Their romance seemed right out of a fairy tale, and their public loved it.

Doug had a perpetual wanderlust, resulting in the couple taking seven around-the-world trips in the 1920s. In Italy, they met with Mussolini, who impressed Mary. On a trip to Russia, the former Czar’s railroad car picked them up at the border, and 35,000 people greeted them at the Moscow train station.

Doug Fairbanks was not lazy. He became known for his swashbuckler movies, swinging from ropes and vaulting across movie sets. His fame spread with The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Robin Hood (1922), The Thief of Bagdad (1924, at a cost of $1.7 million), Don Q: The Soul of Zorro (1925), and The Black Pirate (1926, in early Technicolor). Mary was equally busy, in 1920 releasing both Pollyanna (which made a million dollar profit) and Suds. She played both a boy and his mother in 1921’s Little Lord Fauntleroy. It took fifteen hours of camera work followed by film tricks to capture her kissing herself. 1927’s My Best Girl, with young actor and musician Buddy Rogers, was a smash hit.

DW Griffith worked far away on Long Island; neither he nor Charlie Chaplin were as productive and profitable as United Artists partners as Doug and Mary. Mary, as usual, focused on business aspects. She promoted her films with up to three hundred billboards across the United States.

At the same time, Mary began to ache for the world to see her as something other than a little girl, someone more serious. But her audience wanted her to stay as she was. When she cut off her curls and changed to a short haircut in 1928, the photos made the front page of the New York Times. Into her early thirties, she was still occasionally playing twelve-year-olds, as in 1925’s Little Annie Rooney. In her efforts to be taken more seriously, she hired prestigious German film-maker Ernst Lubitsch; their film Rosita (1923) made over a million dollars but their egos clashed and no more films emerged from the collaboration. Mary reached out to the 2.5 million readers of Photoplay magazine, asking her fans what types of roles they would like to see her play. Twenty thousand letters came back, the overwhelming majority wanting more of the same old “Little Mary.”

Mary’s family continued to slide downhill. Brother Jack’s showgirl wife died of a drug overdose, amidst rumors that she had caught a venereal disease from Jack. He unsuccessfully tried to kill himself. Sister Lottie’s reputation in Hollywood as a “tramp” was even worse. These revelations hurt, as Hollywood was gaining a reputation for misbehavior with the rape trial of comic Fatty Arbuckle and the death of morphine addict movie star Wallace Reid. Fame was taking its toll.

United Artists also struggled. While Doug and Mary’s pictures were profitable, they were not enough to cover the overhead required for international film distribution, and too few other independent projects came their way for distribution. DW Griffith was broke, and Chaplin squabbled with Doug and Mary at meetings of the partners. For a few years, United Artists attracted Joseph Schenck and Samuel Goldwyn to the team. Schenck was a talented executive who later led the Twentieth Century Studio. Goldwyn was a hit-maker but a profane, tough man whom Mary always hated. Nevertheless, they made many successful movies and boosted United Artists’ profits until the boardroom fights drove them out of the company. During the 1920s and 1930s, Mary and Doug each received over $500,000 in dividends from the company, in addition to their earnings on their own projects. United Artists also bought a small group of theaters, including the Egyptian and Chinese theaters in Los Angeles. The United Artists Theater in Los Angeles still stands, replete with a mural of Chaplin, Fairbanks, and Pickford.

Despite all this, Mary carried on in her happy, optimistic way, leading parades, judging contests, laying cornerstones, telling people to keep their chins up, even writing an advice column for the newspapers. The press always found her kind and generous. At most events, Doug was at her side. In 1927, Mary helped found the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the organization that was to later give her two Oscars. Douglas Fairbanks was the first president of the Academy, serving for three years.

The Long and Often Sad Decline

The peak of this beautiful and beloved couple lasted less than twelve years. In addition to the strains at United Artists and the decay of Mary’s siblings, two external factors hit hard: the addition of sound to movies and the Great Depression.

In the mid-twenties, Sam Warner, one of the famous brothers, saw a demonstration of a sound-on-film technology. The sound was so vivid that he looked behind the screen to see the live orchestra, but there was none. Warner Brothers and Fox Studios soon adopted sound, but the industry was resistant. Putting language into film would limit the ability to sell overseas, which represented forty percent of the industry’s profit. Even in America, it might hurt their audience among immigrants. Millions of dollars would be required to re-equip theaters; the entire film-making process would have to change. DW Griffith, arguably the greatest silent film maker, thought the idea would pass and soon be forgotten. Even Mary Pickford thought the idea was “a decadent frill, like putting lip rouge on the Venus de Milo.” But sound did not pass, and by 1930 silent movies were the thing that passed. Mary Pickford made a few sound movies with mixed success, but she never fully made the transition, and soon stopped making films or stage appearances. She came to believe that her silent films were outdated and worthless.

The Depression hit the industry hard. American attendance dropped from eighty million people a week in 1930 to fifty million two years later. Paramount, RKO, and Universal all went bankrupt, and most of the other studios barely survived.

Yet hardest on Mary were her personal tragedies. On March 21, 1928, her beloved mama Charlotte died. She left one million dollars to Mary, two hundred thousand each to Jack and Lottie. It has been said that Mary never really recovered from the loss of her best friend and outstanding business manager. Charlotte had hidden her alcoholism from Mary, but now Mary began to hide her rising habit as well—drunken brother Jack took a friend to her bedroom, where the hydrogen peroxide bottle was full of gin and the Listerine bottle full of Scotch. Doug Fairbanks began to travel alone more often while Mary stayed at Pickfair. He began an affair with Sylvia, the soon-to-be-divorced wife of the British Lord Ashley. He spent his time partying at an English estate. Meanwhile, Mary took an interest in her co-star from My Best Girl, Buddy Rogers, who was twelve years younger than Mary. He was not extremely talented, but was handsome and kind, known as “America’s Boyfriend.”

It appears that Mary and Doug still loved each other, but it was hard for them to make it work. Doug would write Mary love letters even while seeing Sylvia. He invited Mary to join him in Italy, where she confronted him about his infidelity and promptly returned to America. At other times Doug would chase Mary across the United States, or she would beseech him. Finally, Doug returned to California and begged Mary to take him back, day after day. Giving up, he left for New York. In the middle of the night, he departed his New York hotel and sailed for Europe, just missing Mary’s telegram saying that she forgave him, to come back home. But it was too late.

Mary sued for divorce in 1933, which was finalized in 1935. In 1936, Douglas Fairbanks married Sylvia Ashley. Buddy Rogers was madly in love with Mary and begged her to marry him, but she hesitated. Finally, in 1937, she relented and married Buddy—a marriage that lasted until the day Mary Pickford died. Yet even after all that, Doug and Mary would see each other occasionally, and sometimes even hold hands. Doug said, “What a mistake, Mary,” and she could only answer, “I’m sorry.” Both had lost a great deal.

Mary’s little brother, Jack, died in Paris in 1933, and her sister, Lottie, died three years later, both victims of a life of alcoholism and abuse. Mary was the only Smith left.

On June 6, 1939, Mary’s first husband, Owen Moore, died at age fifty-six. Six months later to the day, Douglas Fairbanks also died, also aged fifty-six. At the age of forty-seven, when many people’s careers are peaking, the world Mary Pickford had known—in fact, had made—was almost entirely gone. Worst of all, she had lost her purpose in life. Perhaps to replace them, in the early 1940s Mary and Buddy adopted a boy and a girl. But Mary was not a good mother, and the two children had their troubles, eventually separating themselves from Pickfair and the baggage it carried.

Mary continued to be honored, and she made occasional speeches. She received an Oscar in 1927 and again in 1976. She tried many different projects, from radio shows to writing books. Few were successful. Ideas for producing movies came to naught or died before completion. In 1950, two young lawyers took over operating control of United Artists and in six years it went from a $1 million loss to a $6 million profit. In 1956, she sold her share of the company for $3 million.

As the years went on, Mary’s public appearances became fewer and fewer. Those she did make varied, from alert and sober to drunken and blurry. After about 1963, she spent most of her life in bed (and drinking) at Pickfair—so much so that her legs atrophied and she could no longer walk.

On May 25, 1979, her ever-supportive husband Buddy Rogers rushed her to the hospital after she had a stroke. Four days later, Mary Pickford died at the age of eighty-seven.

In recent years, much more respect has been paid to silent film, even though many of Mary Pickford’s best movies were destroyed or deteriorated over time. Today there is more emphasis on film preservation and restoration. The art of the young Mary Pickford earns more respect than it did in the years following the rise of the talkies. Yet above all else, the incredible persistence and rise of young Mary Pickford and the long, slow decline of the aging Mary Pickford must make all of us ask what our purpose is, what really makes us happy, and how do we deal with life’s ups and downs. Are fame and fortune always worth the price? Despite all the good things mother Charlotte Smith taught her family, she also seems to have shown them to seek salvation at the bottom of a bottle, literally a dead end.

Source: This article is based on the comprehensive 1997 biography Pickford: The Woman Who Made Hollywood, by Eileen Whitfield.