By Gary Hoover — December 2018

One of the myths about great entrepreneurs is that they love risk and are big gamblers. In fact, they usually do everything they can to reduce risk and are rarely true gamblers. But there is always an exception to the rule. This is the story of one of those exceptions, Kirk Kerkorian, perhaps America’s greatest gambler. Starting from the fields of Southern California and fighting his way out of poverty in Los Angeles, this proud son of Armenian immigrants went on to reshape Las Vegas, Hollywood, and Armenia.

Beginnings

In 1890, Kasper Kerkorian fled the Ottoman oppression in his homeland of Armenia to the United States. Ten years later, his son, Ahron, followed him through New York’s Ellis Island, heading to California as a penniless teen. The ambitious Ahron started to haul citrus fruit from the farms to the towns in his horse-drawn wagon. He never learned to read and write English. He and his wife, Lilly, also an Armenian refugee, had four children. The last of these, Kerkor Kerkorian, was born in Fresno on June 6, 1917.

Father Ahron continued his entrepreneurial ways. He saw raisins as storable nutrition for America’s soldiers and by the end of World War I had become the “raisin baron of San Joaquin.” He controlled over one thousand acres on ten ranches and drove a Stutz Bearcat convertible. But then the oft-forgotten recession of 1920–21 wiped him out, and creditors seized all of his assets—often as Ahron chased them off his property with a pistol or a stake. (That same recession hit farmers across the country especially hard, and almost wiped out Sears, Roebuck and General Motors, as well.)

Desperate, the family moved to nearby Los Angeles. As the Great Depression arrived and deepened, the family was repeatedly evicted from their lodgings, and moved again and again. It was a rough way for young Kerkor to grow up. Adapting to the new urban environment, he started going by “Kirk,” which remained his name throughout the rest of his long and interesting life.

By the time he was nine, Kirk was selling newspapers on street corners, contributing to his family’s meager income. He also pitched pennies and bottle caps with his fellow “newsies,” his first exposure to gambling. But the shy, slim kid was often the target of bullies as the family moved from one neighborhood to another. Like his father, Kirk did not back down easily. After being beaten up badly by another youth, Kirk confronted him again. After Kirk got the worst of it three or four days in a row, he noticed that the bully started giving up. They became friends. Kirk throughout his life was known for rarely holding a grudge.

When Kirk was transferred to another school for fighting, his buddy Norman Hungerford (a Swede) got into a fight just to move with him. While Kirk’s rough-and-tumble crowd were immigrants from all over the world, he didn’t venture out of California. Kirk tired of school and dropped out with the equivalent of an eighth-grade education, including some auto shop.

Kirk and his siblings took any jobs they could to help support the family. His older brother, Nish, became an amateur boxer to earn a bit more. As the Depression worsened, Kirk and Norman joined the Civilian Conservations Corps for $30 a month, more than either boy had ever made. The CCC required that applicants be eighteen, so the seventeen-year-old boys convinced their parents to add a year to their ages. Building roads and trails through the high Sierra of Northern California, the two city boys at first could not compete with the strong farm boys. Never one to give up, Kirk toughened up and impressed the managers. After enough time on the rugged mountains, Kirk and Norman returned to Los Angeles.

One night they got a job on the MGM movie studio lot—moving boulders for $2.60, another personal best. Kirk was later to play a role at MGM that neither he nor his friends could have foreseen.

As the 1930s proceeded, Kirk’s entrepreneurial spirit began to emerge. He started buying old cars, cleaning them up, and selling them for a $15 profit, using skills learned in auto shop. In 1937, the twenty-year-old Kirk followed his brother into the boxing ring, where he gradually earned the moniker “Rifle Right Kerkorian.” He won thirty-three out of thirty-seven bouts and was never knocked out. One tough kid!

The Fly Boy

By the fall of 1939, Kirk was working for the Andrews Heating Company, installing gas wall heaters. His crew leader, twenty-five-year-old Ted O’Flaherty, was a veteran navy pilot and would take a quick flight during their lunch hour. At first, the reticent Kirk would stand back and watch, but O’Flaherty finally convinced him to take a ride. Kirk immediately fell in love with the power, the view—the rush—of flying. The experience changed his ambitions from becoming a champion boxer to being a flyer.

Kirk scraped together the money for the expensive $3 per hour flying lessons. He even saved a dollar each lesson by not renting the optional parachute while practicing loops and rolls. In 1940, he hitched a ride out to the Mojave Desert where Florence “Pancho” Barnes operated her Happy Bottom Ranch and Riding Club, home of the exploits of many famous flyers, including the record-breaking Chuck Yeager. Kirk agreed to muck out the barn and slop hogs in exchange for more lessons. Within six months, Kirk was such a good pilot that he qualified for a commercial pilot’s license. In this period, he also met his first of four wives, Hilda “Peggy” Schmidt. They were married in 1942.

Kirk soon became a pilot trainer for a California defense contractor, preaching the old saying, “There are old pilots and there are bold pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots.” Despite being a great, disciplined teacher, Kirk was never comfortable giving speeches, and throughout his life he rigorously avoided the spotlight. Friends would say that he took all the risk but never the credit.

As World War II broke out, Kirk became eager to help in the fight. He worried that not having a high school diploma would hold him back, until a friend secured one for him from a willing school administrator. Offered a commission in the US military, he preferred the freedom of being a civilian. When the Canadians sought pilots to ferry new warplanes to Britain, he jumped at the chance, moving with his wife to Montreal in his first trip outside California. After training by the Royal Air Force, he began ferrying planes across the North Atlantic for the high income of $1,000 a month.

These were some of the most dangerous trips any pilot could attempt. The aircraft did not have enough fuel capacity to make the trip without the right tailwinds, even with extra fuel tanks. Flying at night through the clouds added to the risk. A bit of ice on the wings and a plane could drop like a rock. A variety of planes were moved, including some that were untested and unreliable. In one harsh winter period, only one in four planes made it, the other pilots were lost at sea. Kirk had a few very close calls with death, but he loved it. Few pilots were better at analyzing the wind, fuel, and routing data, and at calculating the odds. By war’s end, he had made thirty-three of the hair-raising eastbound trips.

Driven by his entrepreneurial impulses, he next opened a flight training school in California. In 1945, Kirk convinced a banker at Bank of America to finance his purchase of an Army Air Force surplus five-seat, twin-engine Cessna so that he could also go into the charter business. Soon he was shuttling high-rolling gamblers to an emerging town of 8,500 people in the Nevada desert called Las Vegas. Kirk was “overwhelmed by the excitement of the town.” The adrenaline rush of flying dangerous missions returned. Kirk’s circle of California friends widened—he once flew John Wayne over Arizona looking for movie locations for four days.

But Kirk was always looking for a bigger deal, for the next deal. He sold the flight school and charter business for a profit and bought seven C-47s (also known as DC-3s) from the military. They were cheap, about $12,000 each, because they were stranded in Hawaii with inadequate fuel capacity to make it to California. Despite extra fuel tanks and careful calculations, the first plane, with Kirk at the controls, almost did not make it. For a few tense hours, his family thought he was dead. By tossing everything onboard into the ocean to lighten the plane and save fuel, Kirk and his crew barely made it. He ended up with a nice profit on every one of the planes.

In 1947, he combined his profits with a $15,000 Bank of America loan and $5,000 from his sister Rose to pay $60,000 for a three-plane charter operation at Los Angeles Municipal Airport. He also continued to buy and sell used aircraft, with customers as far away as Brazil. Kirk got a reputation for honesty and fairness. When one plane turned out to be in worse shape than the customer was promised, Kirk gave the customer his money back, no questions asked.

Charter flights to Las Vegas continued. On one occasion, he flew mobster Bugsy Siegel from his Los Angeles home to the gambling city, which was in part pioneered by Siegel’s Flamingo Casino. Bugsy met with his East Coast “partners” (who likely were unhappy with the casino’s profits) and returned to Los Angeles with Kirk. Two days later Bugsy was assassinated in a rain of bullets at his home.

In Las Vegas, Kirk became a familiar sight at the gambling tables. He was not known as much for being a winner, but for his ever-calm and quiet demeanor. He was called “the Perry Como of the craps table” after the popular, relaxed singer of the era.

In 1950, Kirk bought an old four-engine DC-4 for the bargain price of $70,000. The price was cheap because the plane had been used to haul cattle. The insides were a mess and smelled awful. Borrowing $100,000 to buy and clean up the plane, Kirk sold it for $340,000. This was the first year that the thirty-three-year-old made a personal income of $100,000.

Few people saw value where Kirk saw value. He bought the remains of a crashed Lockheed Constellation for $150,000, found engines for it, and made a $600,000 net profit. But Kirk was in love with business, and his first marriage ended in divorce after nine years, in 1951. In 1954, he married again—to English dancer Jean Hardy. They had their first child, Tracy, four years later.

He continued to be enthused about the future of Las Vegas, and in 1955 bought 1% of the new Dunes hotel for $50,000. Like many casinos, it was badly run—perhaps skimmed by the mob—and Kirk lost the $50,000. Kirk said, “I learned then not to invest in a business that I didn’t run.”

By 1960, Kirk had renamed his charter operation Trans-International Airlines and was personally making over $300,000 per year. In 1962, he cobbled together the $5 million in financing required for the small company to buy its first jet, a DC-8 freighter. It was a huge risk for the company, but Kirk saw a big opportunity in hauling loads for the military. His friend at Bank of America loaned him $2 million, and the Douglas Aircraft Company helped make the deal happen. In less than a year, Trans-International’s earnings rose from $250,000 to $1.1 million thanks to the DC-8.

In 1962, the ailing Studebaker automobile company decided to diversify and came calling for Kirk’s well-run charter airline. Kirk took the chance to “take some money off the table.” Including the debt to buy the DC-8, the deal was valued at $10 million, and Kirk got over a million dollars’ worth of Studebaker stock. While Kirk was allowed to keep running the airline, Studebaker management soon interfered, and drove Kirk nuts. Studebaker was not doing well. Kirk sold his stock, and in 1964 bought the airline back for $2.5 million. The uneducated kid from nowhere was evolving into a master deal maker.

In the interim, he used proceeds from the initial sale to Studebaker to buy eighty acres of sand in Las Vegas for $960,000. The problem with the land was that it was just off the Las Vegas Strip—with small parcels blocking access to that key artery. One by one, he swapped land with the owners of those parcels, so that they ended up owning more acreage, but everyone had access to the road. In 1964, he leased his now more-valuable land to Atlanta motel developer Jay Sarno, who built his Caesars Palace on the ground. Kirk received lease payments of $15,000 a month, 15% of the huge casino’s profits, and a suite in the flashy new resort hotel when it opened in 1966. Caesars took the imagination of Las Vegas to a new level: at $20 million, it was the most expensive and biggest casino in history, a home for high-rollers.

In 1965, Trans-International Airlines became a publicly held company. The stock opened at $10.375 per share. Within a few months, Kirk’s shares were worth $66 million. In 1968, financial services company Transamerica acquired the airline for $150 million, putting $100 million into Kirk’s pocket and ending his leadership of the company.

The airline was renamed Transamerica Airlines and lingered on into the 1980s, when Transamerica decided to leave the airline business and shut it down.

Meanwhile, Back in Las Vegas

Caesars Palace had been a huge success, but its operation was infiltrated with mobsters and others connected with financing from Jimmy Hoffa’s Teamsters Pension Fund. Kirk was very uncomfortable with such connections, and in 1968 sold his land under it for $5 million. Including his share of the casino’s profits, he cleared $9 million on that risky gambit.

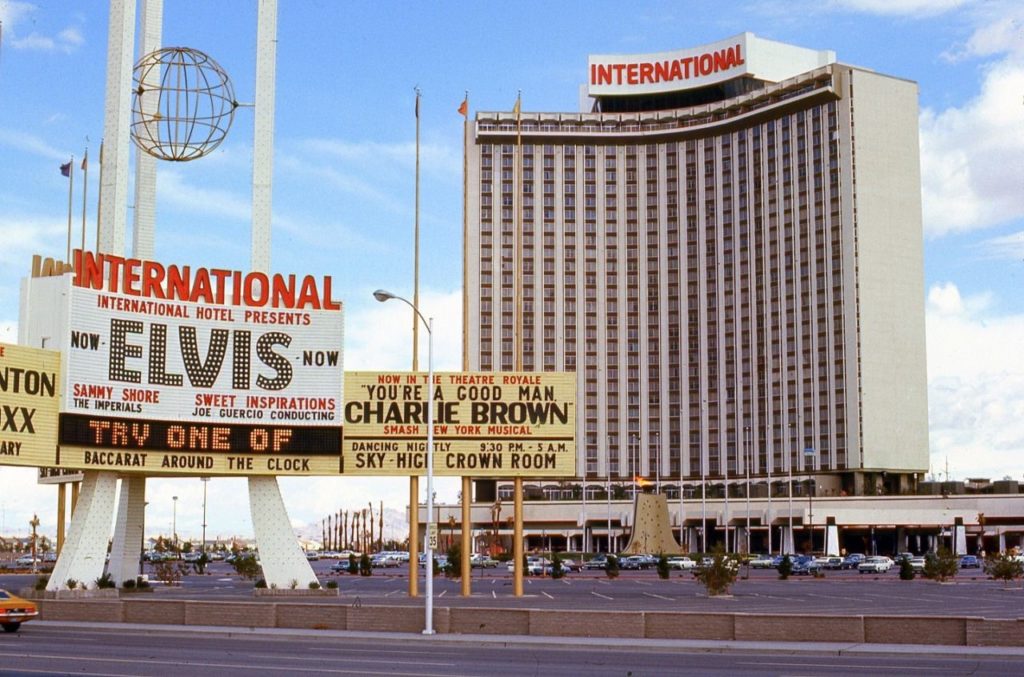

Even before selling the airline, Kirk stayed busy dreaming bigger, much bigger, in Las Vegas. He told a very few friends and advisors of his idea to build the biggest casino hotel in town. He spied a large plot of land off the Strip, next to the new Las Vegas Convention Center. Most told him it was a bad location; it would never work. Billionaire recluse Howard Hughes was buying up casinos left and right and threatened to open an even bigger casino and resort. But Kirk persisted, dreaming of a 1,500-room hotel, the city’s largest and tallest, with the biggest gaming floor. Kirk created International Leisure Corporation and took the company public, raising $26.5 million through the sale of stocks and bonds. Based on Kirk’s reputation, the stock rose from $5 per share to as high as $50. Kirk used some of the money to buy the classic Flamingo casino, just to use it as a staff training ground. After careful planning and analysis, he opened the $60 million International in the summer of 1969.

The International was the world’s biggest hotel and casino. Its big nightclub opened with Barbra Streisand. Kirk’s good friend Cary Grant and other celebrities were present at the opening. After Streisand, Kirk’s seasoned management team coaxed Elvis Presley to perform at the International. Far exceeding everyone’s expectations, Presley sold out concert after concert. The International signed him up to perform for two months a year for five years, for $500,000 per month, or $5 million for the total contract. Such numbers were unprecedented.

Kirk owned 82% of International Leisure Corporation after the initial stock and bond offering. At the time of the offering, his stock was worth $16.6 million. After the opening of the International, his stock was worth $180 million. The uneducated kid from the streets of Los Angeles continued to outsmart the smartest people around. People loved working for him. He was loyal, fair, and generous.

Movie Mogul

Kirk was always on the lookout for a good bet, for undervalued assets—and companies.

The Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio (MGM) was, along with Paramount, the original big Hollywood studio. In its glory days under Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg, it made hits including The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind. But by 1969, the studio had fallen on hard times, its new films losing millions. Kirk saw MGM as “three magic letters.” Working as he always did with industry professionals who could analyze the financial statements in detail, Kirk borrowed millions and fought the old owners hard to buy 40% of the company and take effective control.

But MGM was a mess. Kirk hired new management and gave them orders to cut the losses and raise cash. Valuable real estate was sold off. Props from the great movies were sold off. Kirk was called “the most hated man in Hollywood.” But he saved the company, retaining the MGM brand and its valuable library of classic films.

At the same time, some of Kirk’s past business dealings began to haunt him. Criminal investigations into the Dunes, Caesars Palace, and some bookies Kirk had used led to his name making more headlines. International Leisure Corporation needed another stock offering to pay back debt, but the Securities and Exchange Commission denied their application for another offering, and the stock collapsed. Kirk was now in dire need of funds. He sold his private jet, then he sold his yacht. In desperation, he sold half of International Leisure to Hilton Hotels, which wanted into the Las Vegas market, for just $21.4 million, far less than it was worth only months earlier. Hilton renamed the International as the Las Vegas Hilton, and took over the Flamingo, later buying 100% of the hotels. His net worth dropped by $100 million, but Kirk held onto MGM and its three magic letters.

By 1971, Kirk had survived and again was building up his fortune. Sitting with the management of MGM, he decided the best hope was using those three letters to diversify—by building, for the second time, the biggest casino hotel in the world. Because Kirk never defaulted on a loan, and his word was his bond, the company was able to borrow $75 million to build the MGM Grand on the Strip and fill it with movie memorabilia. At twenty-six floors, over two thousand rooms, and a casino 140 yards long, it would be the largest ever in every dimension. In December 1973, the MGM Grand opened. Dean Martin performed and Cary Grant and other friends were again present. Kirk was back on top. The man was unstoppable.

In 1974, the newly diversified MGM company made more profit than ever before in its history. In nine months, the film studio made a profit of $11 million, while the new casino made $22 million. And Kirk Kerkorian, through continued buying, now owned over 50% of the company.

Even with all these dealings, Kirk’s investing (or gambling?) interests were wide-ranging. He tried to take over Western Airlines, failing but selling out at a profit. He bought the Cal-Neva Lodge and casino on Lake Tahoe, and began construction of a second giant hotel casino, the MGM Grand Reno. In 1980, he made an unsuccessful attempt to take over Columbia Pictures and merge it with MGM.

But in the middle of the Columbia Pictures negotiations in New York, he received terrible news and had to jet back to Las Vegas. In the early hours of November 21, 1980, an electrical fire broke out in the closed deli of the MGM Grand. Before firefighters could make progress, fireballs blasted across the giant casino hall. Hotel guests were trapped in their rooms and died from smoke and noxious fumes. By the time Kirk arrived four hours later, the fire was out but eighty-five people had died.

Kirk ordered the many lawsuits settled quickly and generously, advancing the money out of his own pocket, resulting in his insurance company suing him for giving up too much to the victims’ families. He immediately began plans to rebuild the MGM Grand. He ensured that some of his laid-off people were paid during the interim.

At MGM the movie company, he also sold off the valuable classic film collection for over a billion dollars to an eager (and much younger) Ted Turner’s Turner Broadcasting System. When Ted could not come up with the money, Kirk reduced the price and helped finance the deal because he liked the young entrepreneur.

Kirk never lost his love of an interesting bet. It was a tradition in the casino business to attend the grand opening of a competing casino and lose a bunch of money to wish the competitor good luck. Though not direct competitors, New York’s billionaire Tisch brothers opened a casino in the south of France, and Kirk was there for the opening. He asked the brothers if he could make a million-dollar bet, with the intention that he would lose. They gave him an unmarked orange chip and told the pit boss it was for one million dollars. Kirk bet that the lady at the craps table, who had been winning and winning, would roll a 7 and “crap out.” His odds were 1 in 6. He won. Sometimes it seemed like Kirk could not even lose if he tried.

In 1987, Kirk sold the MGM Grand hotels in Las Vegas and Reno to pinball machine maker and fitness chain operator Bally’s for $550 million, including the assumption of $110 million in debt. Bally’s got the right to keep using the name MGM for three years, after which time the casinos were renamed Bally’s. In the deal, Kirk personally took on any remaining liabilities from the fire, and other shareholders got 20% more than Kirk for each share they owned. Even Kirk’s lawyers were often stunned by his fairness and generosity. It was the thrill of the game more than the score that mattered to him.

Beyond Las Vegas: Armenia and the Auto Industry

In December 1988, a tremendous earthquake struck Kirk’s ancestral homeland of Armenia. Fifty thousand people died; many more were homeless. Though he had never visited Armenia, his California Armenian friends reached out to him. Anonymously, he backed massive airlifts of supplies from California to Armenia. His gifts led to a total of over one billion dollars of aid. Years later, when the president of Armenia wanted to build a highway across the nation, Kirk said, “Would $100 million help?” When newspapers griped that the rich Armenian-American had not helped, Kirk and his benefactors felt forced to make his role public; something he hated to do. He became a hero in Armenia, but only under the agreement that there would be no streets named after him, no monuments built to him.

In 1990, he decided that the nearly bankrupt Chrysler Corporation was undervalued. Kirk spent $272 million to acquire 9.8% of the company. His friends at Bank of America loaned him $800 million to buy more. Eventually Kirk got out of Chrysler—for a $2.7 billion profit. He later made runs at General Motors and Ford, but the latter deal cost him dearly when the recession of 2008 hit Ford’s stock and Kirk decided to cut his losses. (Later, Ford stock rebounded strongly.)

Kirk also continued to “play” in Hollywood, buying and selling the United Artists’ movie company.

Back in Las Vegas

In 1987, he bought two of Howard Hughes’ old properties, the Sands and the Desert Inn. Two years later, for $110 million he sold the Sands to Sheldon Adelson, who had sold his giant computer convention Comdex and thereby entered the casino game. In 1993, ITT Sheraton bought the Desert Inn for $160 million. Kirk was piling up cash again.

Three years after his deal with Bally’s, Kirk could use his three magic letters again. Plans were underway for a new MGM Grand, for his third try at building the world’s largest resort hotel. With giant concert stages, an enormous casino, a “Madison Square Garden West” for his beloved boxing, and 5,005 rooms, Kirk’s vision was far bigger than anything he (or anyone else) had ever attempted before. This “emerald city,” cloaked in green glass, would end up costing a billion dollars. The massive resort opened in 1993.

In early 2000, at the age of eighty-two, Kirk Kerkorian bought out his younger competitor and old friend Steve Wynn’s Mirage resorts for $4.4 billion. The deal included the Mirage, Bellagio, and Treasure Island casino hotels, some of the most prestigious on the Strip. Kirk would soon control half of all the rooms on the Strip. When Kirk’s lawyers insisted that he make Wynn sign a standard five-year non-competition agreement, Kirk refused to do it. He liked Steve “in the game.” Wynn took his $500 million personal stake and immediately began building a new casino.

At the age of eighty-seven, in 2004, Kirk’s company spent $7.6 billion to buy Mandalay Resorts, including Luxor and Excalibur.

Before the 2008 recession, Forbes magazine had estimated Kirk’s wealth as high as $18 billion. But after that crash, Las Vegas business slowed and his next big project, CityCenter, was under water. Some estimates put the wealth of the ninety-one-year-old Kirk as “low” as $2 billion. His losses on Ford Motor did not help.

Yet Kirk continued to dream and dream big, right up until his death in 2015 at the age of ninety-eight. He never stopped making deals. He never stopped playing.

MGM Resorts International Today

Kirk’s company is now named MGM Resorts International. It has a market value of $13.6 billion. The holding company he created for charitable purposes, Tracinda (named after daughters Tracy and Linda) owns about $675 million worth of the stock, after selling off most of its interest.

MGM Resorts International owns a half interest in CityCenter with its Aria resort, and full ownership of Bellagio, Circus Circus, Excalibur, Luxor, Mandalay Bay, MGM Grand, the Mirage, New York-New York, Park MGM, and 42.5% of the T-Mobile Arena. The company also has casino operations stretching from Massachusetts to Mississippi to Macau.

Out of one man’s drive and vision came this company, one of the most important hotel and casino operators in the world.

CityCenter, Las Vegas

Kirk Kerkorian the Man

The above paragraphs only scratch the surface of the complex life of Kirk Kerkorian.

While he had many lifelong friends, whom he supported in every way possible, he was not so lucky in love. One of his many girlfriends, former tennis star Lisa Bonder, wanted to be “the world’s richest woman.” She claimed her baby was Kirk’s, and even faked DNA evidence to prove it, but better evidence later proved otherwise. Nevertheless, Kirk set aside $50,000 a month to raise the child and left her $7 million when she turned eighteen. (She later successfully sued to raise that to $8.5 million.)

As of 2018, court fights over Kirk’s fortune continue. He left most of his money to charity, but set aside sums of up to $7 million each for old friends and his key advisors.

Kirk Kerkorian was always a mystery to the press—he refused to do interviews or be photographed. He never made speeches. At the openings of his dream hotels, he would never appear on stage and take credit. But he was far from a recluse like Howard Hughes—he dined out often. He was in his casinos. He walked to meetings without bodyguards and drove himself in his Ford Taurus or Jeep.

Kirk was a fitness fanatic, lifting weights into his nineties. In his eighties, he was rated one of the top three tennis players in the nation in his age class. He had no use for slow-moving golf.

He was always on time and despised anyone being late.

He hung out with the most famous people, from Cary Grant to Elvis Presley and Mike Tyson. But he was always in the shadows. No matter who he called, he would first ask, “Is now a good time?”

His friend and former waiter Mike Agassi was so grateful to him for job opportunities that he named his son Andre Kirk Agassi after Kirk. Andre went on to tennis fame.

Even his business adversaries noted that he was calm and polite, unless you tried to cheat him, in which case he had a fiery temper. But he let bygones be bygones and kept “moving on.” His handshake was as good as a contract, even if a better offer later came along.

Like the other individuals we have covered in this American Originals series, Kirk was one of a kind. There was no mold or stereotype that could fit Kirk Kerkorian. But those who knew him wept at his funeral, and those who did business deals with him always respected his brilliance and vision. We should all be amazed at what someone with an eighth-grade education can accomplish if they see opportunities where others only see disaster . . . or sand.

Source: This story is based on the outstanding and well-written 2018 biography of Kerkorian, Gambler: How Penniless Dropout Kirk Kerkorian became the Greatest Deal Maker in Capitalist History, by William C. Rempel.