Few industries have had a greater impact on the world than our airline system. This global network was built over a period of forty years by a handful of leaders who pioneered on dangerous and shaky grounds. Pre-eminent among them was Cyrus Rowlett Smith, always and forever known as “CR.” At the age of nine, his father deserted his family: his wife, CR, and six younger siblings. With his mother’s support, the youngster struggled and worked his way to the University of Texas at Austin where he studied accounting. Setting aside his natural entrepreneurial energies, he ended up as an accountant for a tiny airline in the embryonic airline industry.

In 1934, at the age of thirty-five, he became the head of American Airlines, the nascent industry’s largest company (with annual revenues of under $5 million). Few passengers risked flying. Carrying airmail for the Post Office was viewed as the only way to make money in the airline business. When CR retired thirty-four years later, in the jet age, he and the company he devoted his life to had led the way in safety, service, marketing, and aircraft innovation. While most of the early airlines disappeared or were bought by other carriers, American continues on as one of the world’s largest airlines. Here is the story of this remarkable man and his beloved company.

Rough Start

Cyrus Rowlett Smith was born into poverty on September 9, 1899, in Minerva, Texas. He was followed by four sisters and two brothers. Nine years later, his “religious fanatic” father walked out on his wife, Minnie, and the family and never returned. Minnie, however, was not without ambition. She became a school teacher and active in politics, leading to acquaintances with people in high places—a tradition her son later perfected. By taking in boarders, enduring and scrimping, she made sure that all seven of her children received at least some college education.

As the oldest man in the family, nine-year-old CR took a two-dollar-a-week job as an office boy for cattle baron C. T. Herring. For five years, he told visitors that Herring “was not in,” then proceeded to be regaled with stories of the Old West as Herring reeled them off, his boots up on his desk. Later, as the chief of a major corporation, CR was also known to keep his boots up on his desk. And the life, lore, and art of the Old West remained a lifelong passion.

The Smith family moved to Whitney, Texas, where CR held a variety of odd jobs, including manual labor. When he was just sixteen, he was hired as a bookkeeper and teller for the First National Bank of Whitney at thirty dollars a month. A year later, he moved to Hillsboro, Texas, for higher pay at a cotton mill.

Despite never earning a high school diploma, CR was admitted on a probationary basis to the business school at the University of Texas in Austin (now the McCombs School of Business, renowned for its accounting program). He earned good grades and was president of his Junior Class. But he was also entrepreneurial. Throughout college, he operated “CR Smith and Company” which gathered lists of company stockholders from Texas corporation filings and sold them to New York and Chicago investment firms. He copied the names and addresses of new parents, selling the lists to makers of baby products. Simultaneously, he took a part-time job as an examiner for the Federal Reserve Bank. By the time he graduated in 1924, he was making $300 a month ($4,500 in today’s money).

With his diverse experience, CR was quickly hired as a junior accountant in the Dallas office of the large accounting firm of Peat, Marwick, Mitchell, and Company. At $150 a month, this was a 50 percent reduction in his income. His skill, quick mind, and tireless efforts, however, soon led him to be assigned to some of the most diverse accounts: cigar factories, movie theaters, oil companies, and insurance companies. When assigned to the insurance industry, about which he knew nothing, he spent five days in the library, “reading up” on the industry day and night. He then was promoted to senior accountant, specializing in the highly complex public utilities industry.

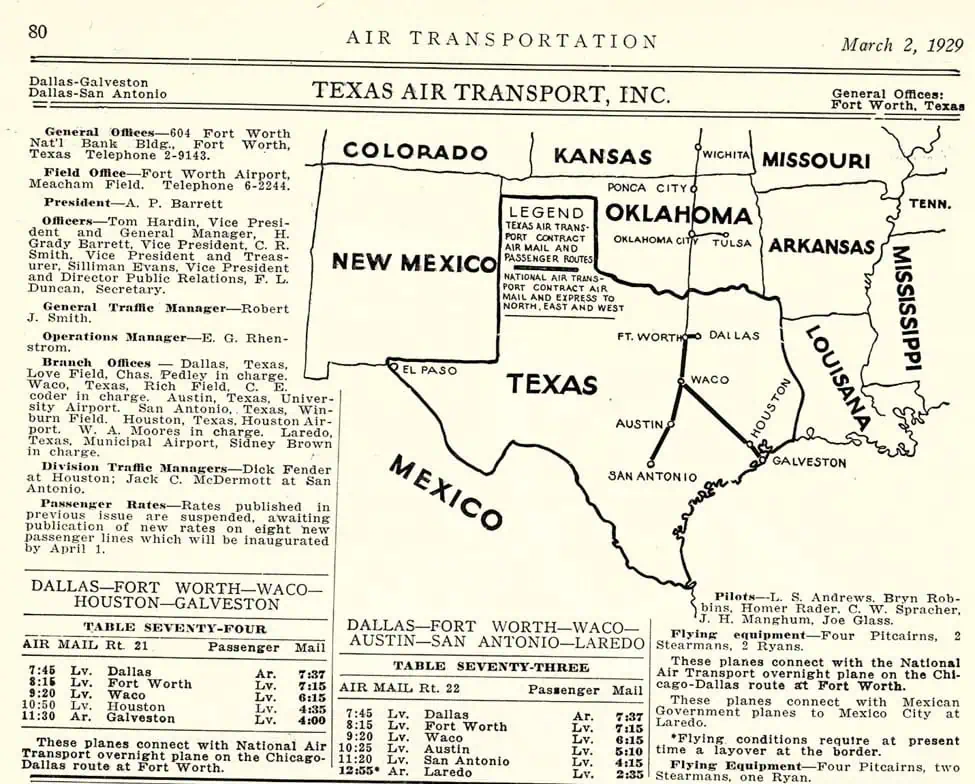

After two years of work for Peat, Marwick, CR came to the attention of businessman A. P. Barrett, who headed the Texas–Louisiana Power Company. Barrett hired him as assistant treasurer of the electric utility in 1926. Barrett also controlled the small Texas Air Transport, one of dozens of tiny airline startups around the United States. In 1928, Barrett asked his young accountant to take over the books for his airline business and watch over operations. Smith responded, “I’m not interested in aviation,” one of the greatest wrong predictions in the history of business. But Barrett persisted, telling Smith to give it a try, and that he could return to the utility business if he did not like it.

In 1929, Texas Air Transport acquired Gulf Airlines and was renamed Southern Air Transport. CR went to his new boss at the little airline, a pilot, and told him, “Teach me to fly and I will teach you accounting.” The young accountant did learn to fly, though it never became a regular part of his life. His pilot boss did not learn accounting, and soon found himself reporting to Smith instead of the other way around. To call the airline industry immature at that time would be an understatement. Let’s take a look at the industry that CR Smith walked into.

The Early US Airline Industry

Although the Wright Brothers had made the first powered flight in 1903, it was not until January of 1914 that the first US “airline” flew a regularly scheduled route. The St. Petersburg–Tampa Airboat line lasted four months, one winter tourist season. World War I turned the nation’s focus to military aircraft, away from the possibilities of “commercial aviation.” After Prohibition was enacted in 1919, a few airlines flew passengers to the more alcoholic retreats of Cuba and the Bahamas. At the time, not only were airplanes considered unsafe, but their average speed including refueling stops was about 75 mph, not much faster than express trains. Airfields only gradually added lights to allow night flying. So it was not until the early- and mid-1920s that any serious progress was made toward regular air service. Small airlines and flying schools were scattered around the country. Many were funded by wealthy young men seeking thrills, in both travel and finance. Early backers included members of the Guggenheim, Whitney, and Rockefeller families.

By the late 1920s, the future of aviation was attracting Wall Street, not unlike the more recent infatuations with investments in the internet and marijuana. Investors wanted in on the ground floor, and bought companies that flew airplanes, taught pilots, made airplanes and parts, and operated airfields.

Among the first to act was Clement Keys, who in 1903 at the age of twenty-seven had become the railroad editor of the Wall Street Journal. Observing trends in transportation for two decades, Keys saw the future of aviation, and in December 1928, organized North American Aviation, raising $30 million to invest in the industry. By the early 1930s, North American controlled Eastern, Northwest, and TWA airlines, in addition to manufacturing aircraft and parts. Even the most powerful companies got interested in aviation: General Motors bought a controlling interest in North American in the 1930s and Ford produced the famous tri-motor aircraft.

Another company, United Aircraft and Transport Company, soon followed in February of 1929. United was formed around the Boeing airplane factory, Pratt & Whitney engines, and Boeing’s airline, which evolved to become United Airlines.

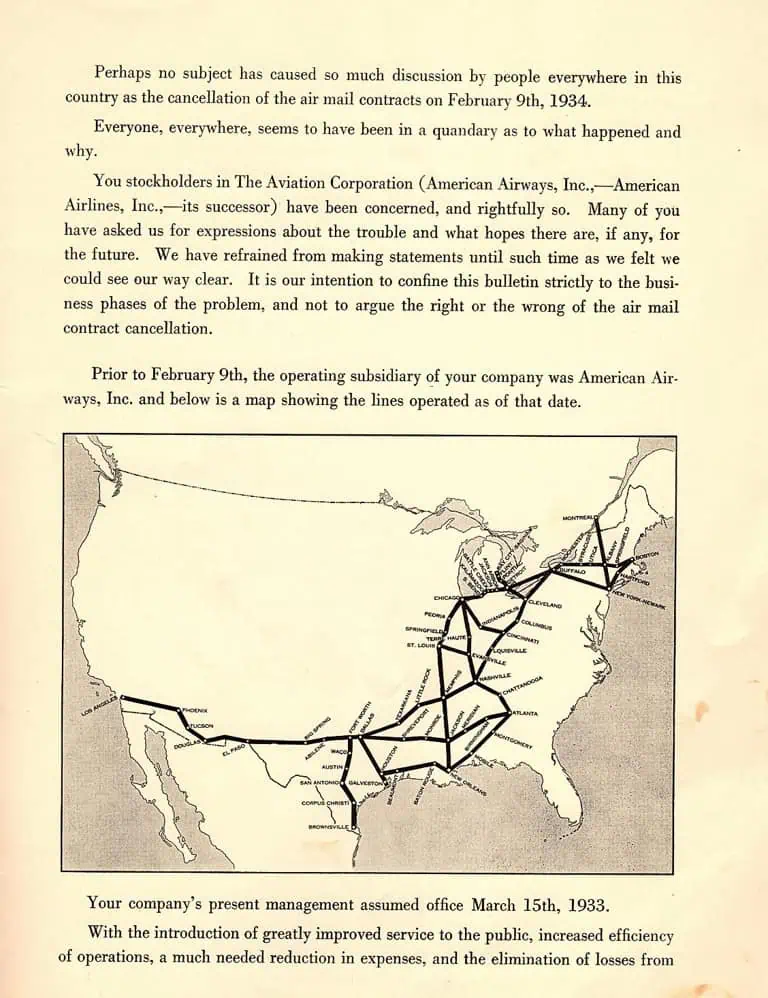

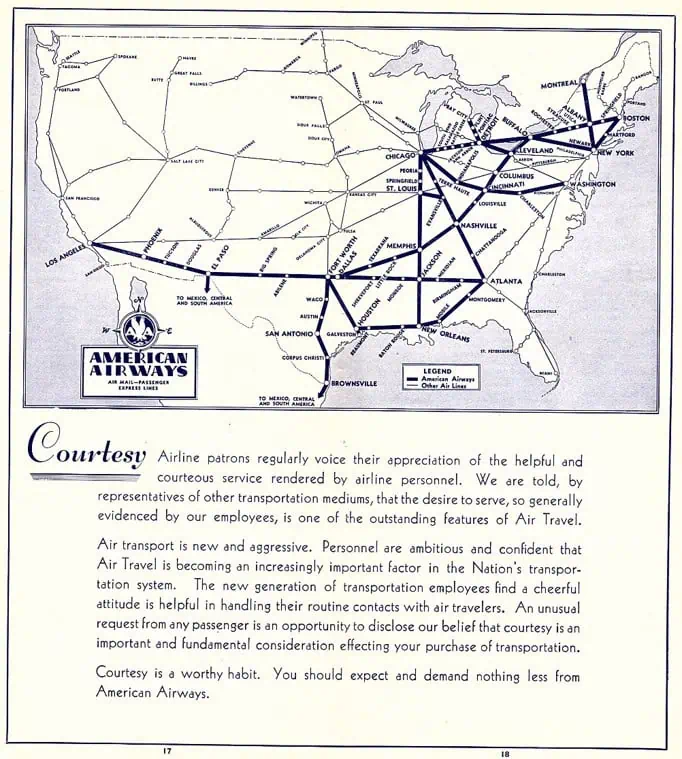

A third group of investors, initially led by Sherman Fairchild (whose father was a founder of IBM) raised $35 million in May 1929 to fund the Aviation Corporation, commonly known as AVCO. While North American and United from the beginning aimed for a coast-to-coast system of airmail lines, AVCO was formed around a gaggle of small airlines whose routes did not even touch each other. They included airlines with the ambitious names Transamerican and Universal. In the next few years, AVCO acquired enough airlines to piece together a coast-to-coast route, but to fly west from New York passengers first had to fly north to Albany, then south to Nashville before proceeding west to Dallas and Los Angeles. The small airlines of AVCO were separately run, with different flying rules and a huge range of aircraft types. Like the other two aviation holding companies, AVCO owned everything from flying schools to airplane parts makers. Flying was only expected to be an alternative to trains for the rich and the brave. None of these companies believed an airline could make money on passengers alone.

In January 1930, AVCO acquired Southern Air Transport, including among its managers treasurer CR Smith.

Scandalous Times

Despite the enthusiasm of Wall Street, the airline industry next saw tumult, which CR survived.

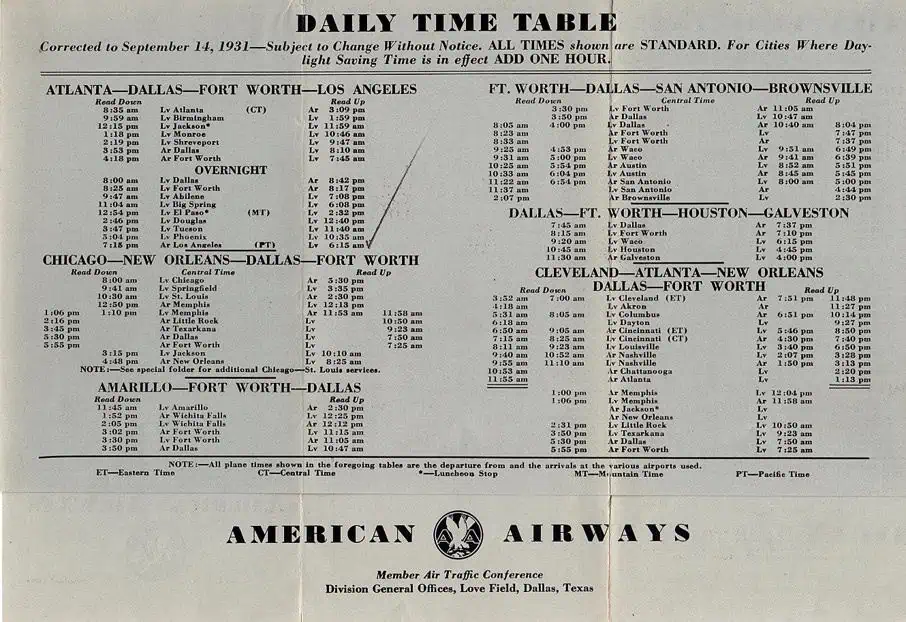

In 1930, President Herbert Hoover’s strong-willed Postmaster General Walter Folger Brown called together the key leaders of the fledgling airline industry. Brown, who oversaw the airmail contracts, which were the lifeblood of the industry, wanted to see a rational national system of well-financed, strong airlines. Forcing mergers and re-allocations of routes among the airlines, Brown advocated three transcontinental routes: a northern route from New York to San Francisco via Cleveland, Chicago, and Cheyenne which went to United; a central route from the East Coast to Los Angeles via Pittsburgh and St. Louis which was given to TWA; and a southern New York to Los Angeles route via Dallas, for AVCO. CR Smith was the manager of the “Southern Division” of AVCO, part of this transcontinental system, but then was promoted to a management role in AVCO’s entire Chicago-based American Airways system.

After Hoover’s defeat at the hands of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, Democratic Party leaders had no love for the policies of the Hoover administration. When a reporter turned up what he believed were inappropriate actions on the part of Brown and the aviation companies, a Senate investigation was unleashed. Brown’s meeting of airline bigwigs received the moniker “The Spoils Conference,” and made for “scandalous” headlines. While later historians question the validity of the politically motivated attacks on Brown and the airlines, the net result was the temptation to nationalize the airlines. Cooler heads prevailed, but carriage of the airmails was assigned to the US Army and its small air corps. However, the army pilots did not have the experience of the airlines: twelve army pilots died in crashes within a few weeks.

Realizing that the mails needed to be returned to the airlines, the government decided to start the system anew, ending Brown’s system. No airline that attended the maligned Spoils Conference could bid on airmail contracts, and no executive involved in the conference could participate in the industry. In addition, the companies were required to separate aircraft manufacturing activities from airline operations. Finding a loophole in the legislation, the larger carriers simply changed their names, re-incorporated, and bid for their old routes. United, TWA, and American Airlines (formerly the American Airways division of AVCO) resumed operation of their northern, central, and southern routes. The separated manufacturing divisions became United Aircraft, North American, and AVCO, respectively.

Fortunately for American, and for the future of the industry, CR Smith had not attended the Spoils Conference, and could remain in the industry.

Creating a Modern Airline

Smith’s career in these early years did not start out smoothly. As the above-described industry changes were taking place, there was a battle for control of AVCO. Smith sided with the men he worked for when they got into a battle with the maverick entrepreneur Errett Lobban “EL” Cord. Cord, a very smart former automobile salesman who controlled the famous automakers Auburn, Cord, and Duesenberg, became interested in aviation and founded Century Airlines in the Midwest and Century Pacific on the West Coast. Cord was one of the very few investors who believed there was a future in carrying passengers. His airlines had no airmail contracts, yet were profitable while AVCO was losing millions of dollars.

In 1932, AVCO bought his airlines rather than try to compete with them, and Cord became an AVCO shareholder. Cord was upset that AVCO was badly run and losing money. In a battle to buy up the company’s stock, Cord won voting control and ousted the old top management. He also, like Smith, believed that the company should pursue passengers rather than relying on the government’s airmail contracts. But Smith had picked the wrong side. Cord had him demoted from a position at American’s Chicago headquarters to again head only the Fort Worth-based Southern Division. Over time, as Cord watched CR’s energy and intelligence in action, he changed his mind about Smith. With Cord’s blessing, the thirty-five-year-old CR Smith became president of American on October 26, 1934. Cord then backed away from management, leaving the airline in Smith’s capable hands, though they remained lifelong friends.

At the Southern Division, Smith had purchased Curtiss Condor aircraft. Unlike most competitors, these were roomy airplanes, which had enough space for sleeping berths, like those in a Pullman railroad car. Passengers loved them, despite the fact they tended to catch fire and were hard to fly. Soon retired, these planes marked CR’s lifelong obsession with customer service and amenities.

American had become the largest carrier, but CR wanted to make it the best. The company was still an uncoordinated group of separate lines. It lacked the “professional slickness” of William “Pat” Patterson’s United and the “technical proficiency” of TWA, often the leader in introducing new aircraft. Operating in a highly regulated industry where authorities in Washington had to approve every route and fare change—often taking years to do so—CR realized that customer service and marketing were what could differentiate his company, as well as using the most modern possible “equipment” (airplanes).

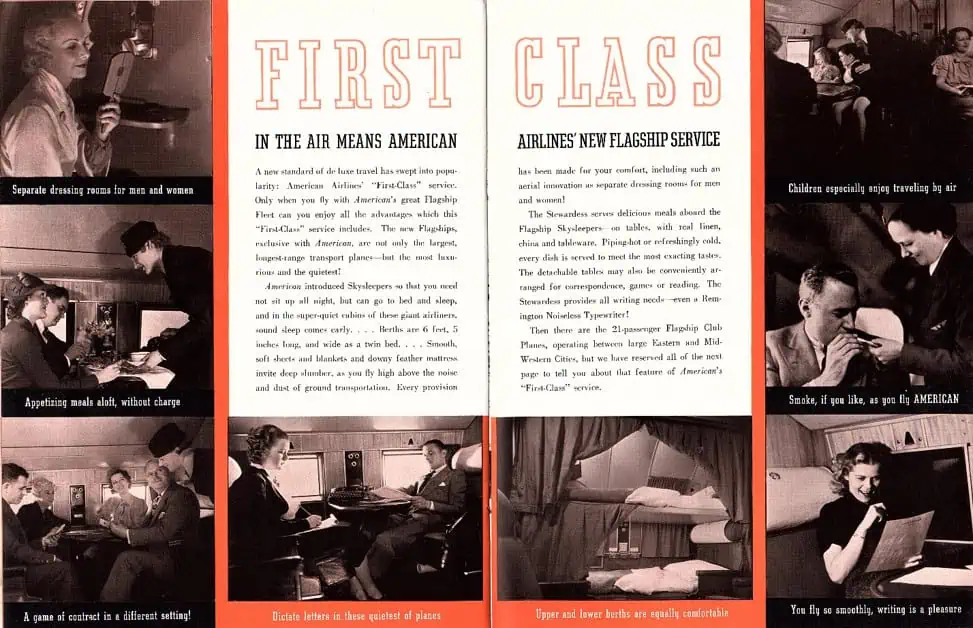

American 1930s Publicity Photos

Leading the Way in Customer Service and Marketing

At the start of his tenure, morale was low at American. On his first day as president, CR made a decision that was easy to execute. He ordered new uniforms for his pilots, improving their look and standardizing them across the company.

Smith always kept an eye—and hand—on marketing. The man had a natural flair for showmanship. Like the crack railroad trains of the era, each flight had a name—including the American Arrow, the American Mercury, and the American Eagle.

On the front right side of the plane, he placed a flag with the American logo on it. The pilots opened their window and placed the flag before each take-off. For many years, because of the flag’s right-side location, American’s “flagship” planes had their doors on the right side so passengers saw the flag, while other airlines had left-side doors. It is hard to imagine these early days of flying—one American pilot was known to put chicken bones on a string out the window, dangling them beside the windows of confused passengers a few rows behind him.

In the 1930s, Smith admired the honorary titles of Kentucky Colonels and Texas Rangers, bestowed upon prominent people. So he created the Admiral’s Club, an informal list of key customers, just a name. Later, CR and American were supporters of New York Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia’s desire to open a big new airport on Long Island. American moved its headquarters there when service began in 1939. Mayor LaGuardia, a veteran military pilot, had a fancy office in the terminal building. When he bragged to reporters about how every inch of the flashy new airport was leased out for restaurants and concessions, they pressed back, “But what about your big office?” The mayor had no choice but to respond, “I will lease it out, too!” American grabbed the space, and the first physical Admiral’s Club was created. Other locations were soon opened, and by 1967, there were 90,000 Admiral’s Club members, far ahead of any other airline’s copycat program.

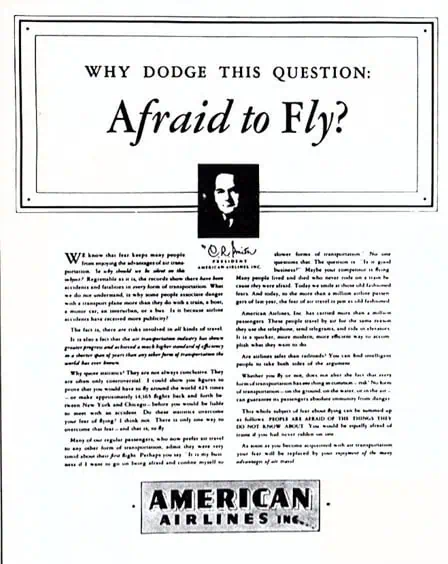

The airline industry had a taboo against talking about safety with the public, preferring to stay silent and not jinx anything. Yet studies showed that fear of flying held the industry back. In 1937, CR ran a highly controversial ad headlined “Afraid to Fly?” Smith personally signed the ad. The industry was aghast, but it was soon shown that the ad worked to the benefit of all the carriers. No one ever said CR Smith lacked guts, which he always trusted.

While United Airlines had the first stewardesses, they became a key part of Smith’s plan. Initially, they were required to be nurses—as much for their caring personality and professional reputation as for any real medical needs. The requirement was dropped when nurses were in short supply during World War II. Each stewardess was required to remember the identities of each of the passengers (twenty-one of them at the time). Remember their tie, their company, their name—something. One stewardess remembered Harvey Firestone as “the tire man” but then mistakenly said to him “Are you enjoying the flight, Mr. Goodyear?” Smith later (in 1957) developed a huge training facility for stewardesses, then other personnel, in Fort Worth. A gambler at heart, CR won the option to buy the land from a reluctant seller, a Texas friend, in a game of rummy. The term “stewardess” became outmoded when male flight attendants were first hired in 1972.

Smith also gambled on new ideas in order to improve the flying experience. He created Sky Chefs to cook the food for flights and open better restaurants in airports. While the restaurants are long gone, Sky Chefs, now owned by Lufthansa, still prepares much of the food for the world’s airlines. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the company dabbled in a hub-based air cargo service and bought a small airline that served Europe. Neither experiment lasted, as Smith refocused the company on the key domestic passenger service (American years later entered global travel in a big way). Under CR, the company made numerous attempts to buy other airlines, including Eastern, only to be rebuffed by federal regulators.

In those days, rather than driving to the airport, many passengers went to the city airline ticket office where a bus took them to the airport for their flight. In New York, the carriers shared a City Ticket Office at 42nd Street and Park Avenue. There were so many buses that they were jammed up and often delayed by traffic. Against great opposition, CR convinced his fellow airlines to open a large new facility closer to the Queens–Midtown tunnel, out of Manhattan’s densest midtown traffic, with easy access to LaGuardia (and later Idlewild, now called JFK). The East Side Airlines Terminal opened at 37th Street and Second Avenue in 1953, followed by a West Side Terminal to serve Newark two years later.

In another Smith idea, from 1953 to 1968, American sponsored an unusual all-music radio show on CBS that ran from 11:30 at night until 6:00 the next morning. “Music ’Til Dawn” was hugely popular and long identified with the airline.

Every detail mattered to CR Smith. He spent $400,000 just to put better coffeemakers on his planes. Curbside baggage checking was another American innovation.

Perhaps the most important innovation, for customers and the company, that came out of Smith’s era was SABRE—the Semi-Automated Business Reservations Environment. Smith happened to sit next to IBM chief Thomas Watson Jr. on a flight. When Watson asked Smith what his biggest challenge was, Smith said, “Handling reservations.” While American had led the industry with its largely manual Reservisor system, it took forty-five minutes to complete a reservation. By the time American and IBM figured out SABRE and put it into operation in 1962, that time was reduced to seven seconds. The airline could then handle eighty-five thousand calls a day. SABRE cost American $40 million, the same as four 707s.

Technical Innovation

In 1934, American’s confusing mix of aircraft placed it behind its key competitors. CR hated being behind the competition in any regard and wanted to standardize the aircraft used by American. One of his most important contributions to aviation was his leadership in developing new planes.

United had the first all-metal airliner, the Boeing 247. TWA was flying the Douglas DC-2, Douglas’s first successful commercial airliner. But Smith was not happy with the DC-2’s design. With fuel stops, it took up to twenty hours to cross the country, depending on the winds. It could carry the mail, but with only fourteen seats, not enough passengers to make money on a flight. It was hard to fly and hard to land. CR wanted a bigger, better, faster plane.

With his top engineer, Bill Littlewood, alongside, in December 1934 CR telephoned Donald Douglas, begging for a better airplane. CR wanted a plane that could carry twenty-one passengers in the daytime, fourteen in overnight berth mode. Douglas said, “No way, we cannot even keep up with orders for the DC-2. There is no way to justify the development costs of a whole new aircraft.” But CR and Littlewood would not yield. They upped the ante by promising to order twenty of the new planes, sight-unseen, if Douglas would build them. Douglas repeatedly tried to hang up, but the American men kept him on the phone for over two hours. Donald Douglas finally relented, agreeing to give it a shot.

The call, back in the days before unlimited calling plans, cost $335.50 ($6,500 in today’s money). CR never signed a formal contract for the planes until much later—he would have had to put up a deposit on the twenty-plane order, money which American did not have. Soon after the call, CR flew to Washington where he met with fellow Texan Jesse Jones, head of the government’s Depression-era Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Smith said, “Jesse, I’ve read that the RFC was set up to ward off financial disaster. Well, American Airlines is a disaster if you don’t make us a loan.” CR left Jones’s office with a $4.5 million loan, enough to finance the order that he had already placed.

And thus was born the Douglas DC-3, the most successful airliner in aviation history. Its 180-mile per hour cruising speed made it the fastest airliner. On June 25, 1936, American inaugurated its first regularly schedule flight, from Midway to Newark in three hours and fifty minutes, with CR and thirteen passengers aboard. That September, American began overnight transcontinental sleeper service—fifteen hours and fifty minutes from Glendale, California, to Newark, including refueling stops in Tucson, Dallas, and Memphis.

American started running ads promoting speed, saying, “When your competitor has reached Gallup, you’ll be in New York.” The airline toured the planes around the US. In Detroit, American drew a crowd of 110,000 people to see the amazing giant. The American DC-3 fleet eventually numbered ninety-four aircraft.

In 1937, American earned two-thirds of its revenue from passengers, not mail. By 1938, American was making its first consistent profit—$200,000 a year. To celebrate, CR sent every one of American’s two thousand employees a check—$25 ($460 today) for employees who had been with the company at least a year; $15 for more recent hires. Relative to the company’s profit, this was a big bonus.

Between 1935 and 1946, more than ten thousand DC-3’s were built, used by the military and airlines around the world. By 1939, DC-3’s carried 90 percent of all US airline passengers. A few of the nearly indestructible planes are still flying today.

American’s technical leadership, driven by Smith, was not limited to airplanes. In 1934, dispatcher Glen Gilbert invented a flight-tracking system, using little model planes on a big map table, which was then shared with the government and the other airlines.

After World War II, CR and American played a key role in the development of the very successful and economical Convair CV-240, which replaced the DC-3’s on short hauls. Trying to keep up with TWA’s fast Lockheed Constellations, American joined with United in the development of the four-engined Douglas DC-6, which was used on longer routes. CR Smith was always looking for a competitive edge: both aircraft were pressurized, an innovation spurred by American’s customer surveys. The DC-6 also introduced air-conditioning to the airline and was considered one of the best planes ever made.

Smith and his executives also drove the creation of the Douglas DC-7, which could fly coast-to-coast without stopping, in both directions, no matter the headwinds. American’s non-stop transcontinental DC-7 service began in November 1953. This aircraft, however, had engine reliability issues and was soon outmoded by the arrival of jets.

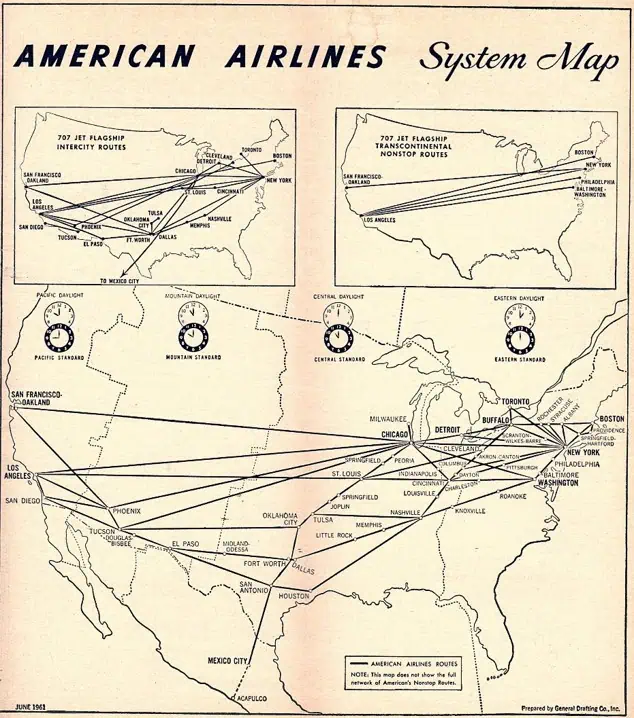

When the jets arrived, airline industry leaders, including Smith, agreed that Douglas’s planned DC-8 would be a better plane than Boeing’s proposed 707. They all knew and trusted Douglas, whereas Boeing was primarily a supplier of bombers and other military aircraft. Yet Douglas moved slowly, and the Boeing was the first in the air. Unwilling to wait, CR joined Pan American’s Juan Trippe in being a launch customer for the Boeing 707, offering jet service months before his top domestic competitors. American introduced transcontinental jet service from New York to Los Angeles on January 1, 1959, the first trip taking four hours and three minutes. Arch-rival United did not begin its transcontinental service until the arrival of the DC-8 in September 1959.

American continued to be the largest airline until the 1961 acquisition of Capital Airlines by United, which gave United an extensive network of routes in the northeast and down to Florida.

Industry Leadership

As indicated above, CR Smith thought not only of the success of American, but of the entire industry. In 1936, he was key to the formation of the Air Transport Association. When the executives of the major airlines agreed to give free passes to the association’s executives, cheapskate Eddie Rickenbacker said he did not want them flying for free on his Eastern Airlines. CR demonstrated his wry sense of humor by saying, “Don’t worry, Eddie, they’ll only try Eastern once.”

Smith, along with United’s Pat Patterson, worked tirelessly to promote the industry, to get better regulations out of Washington, to improve service, safety, and reputation. If a competing airline suffered a crash, American’s top experts were onsite in a heartbeat to figure out what went wrong.

During World War II, CR Smith stepped away from his beloved airline to help run the military air transport system, ultimately resulting in the rank of General. American crews flew over one thousand flights over the treacherous “hump” above the Himalayas between India and China, carrying over five million pounds of cargo.

During the Berlin Airlift of 1948–49, American again pitched in, carrying twenty-eight thousand people and thirteen million pounds of cargo in 274 days.

In 1969, CR Smith finally retired. He served briefly as secretary of Commerce for fellow Texan Lyndon Johnson. But his successor at American was not up to the job, and the company hit a rough spot. In 1973, the board of directors begged him to come back as interim CEO while they searched for a more permanent leader. Reluctantly, CR returned for six months, taking no pay, doing what he felt was the right thing for his airline. Morale at the company instantly improved.

CR Smith the Man and his Management Style

CR Smith was a classic example of a man whose company was his life. In 1934, he married Elizabeth Manget and they had one son, but seven years later they divorced. Elizabeth said, “I love the man, but I can’t be married to an airline.” CR never remarried. He understood his priorities, and their impact on others, though sometimes he had to be reminded that Sunday was not a good day to schedule a meeting. The clock never meant anything to him; he worked for American Airlines’ success 24/7.

While he was obsessed with the airline, he was not without hobbies. He loved to hunt and was an expert fly-fisherman. He was also an expert poker player.

And he loved the Old West. His New York City apartment contained a large collection of cowboy records. The headboard of his bed was a real wagon wheel, the footboard an oxen yoke. The bedside lamp included a Colt pistol. The drapes were in the shape of leather chaps. There were cattle skulls and steer horns everywhere. Smith became an expert collector of valuable Western art by Frederic Remington and Charles Russell, some of which he gave to friends.

The most common adjective written about CR Smith was that he was “decisive.” He sought advice and suggestions but never shared decision-making. He did not like committees, meetings, or long memoranda. Upon hearing one long-winded speech, he commented, “He sure unloaded an empty wagon, didn’t he?” He typed all his own letters, thousands of them, usually brisk and brusque, just the way he spoke. When a reporter asked him how he felt about his mother, his laconic reply was, “I liked her.”

Smith hated pomp. He said, “I’ll fire any guy who thinks he’s an executive.” Everyone in the company called him Mr. CR or just CR. He continually flew around the system, easily talked to passengers, and carried luggage for the stewardesses (whom he called “my girls”). In the early days, he knew everyone in the company. His office door was always open to anyone. In his first offices at Chicago’s Midway Field and New York’s LaGuardia, his office was on the second floor of the hangar, with open windows so he could call out “Come on up!” to the pilots on the taxiways.

When flight crews were stuck in New York where he lived, away from their homes on holidays, CR would take them out to dinner or feed them at his apartment. At one dinner at his favorite restaurant, New York’s 21 Club, he gave each of the twenty-one people present one hundred acres of land he owned near Phoenix. All of them but the maître d’ quickly sold the land—he became a millionaire “because of CR Smith,” as he later told his friends.

When CR caught stewardesses pouring the airline’s alcohol into their own flasks to take home, he gave them $50 bills and told them to write him if they could not afford their own liquor.

CR Smith was undoubtedly tough in many regards. He once flew into the Knoxville station unannounced. One employee was in the office, the phone was ringing, but the employee did not answer it. He said it was the sale phone, not his department. CR picked up the phone and answered the call. After hanging up, the employee said, “From the way you answered that, you must be with American.” Smith swiftly replied, “I am, but you’re not. You’re fired!”

People called him “a poker-playing Texan who couldn’t be bluffed, bullied, or bought.” But his word was always good. Competitors both feared and respected him.

CR Smith died in 1990, at the age of ninety, leaving behind a legacy of courage, leadership, innovation, and above all else, a great airline.

American Through Today

In 1937, early in CR Smith’s tenure, American’s annual revenue was $10 million. As airplanes improved and passengers felt more comfortable, revenue rose to $115 million in 1950. By 1955, it was America’s twelfth largest transportation company, behind eleven railroads. In 1968, the final year of Smith’s reign, revenues reached $957 million, ranking fifth behind two railroads, United Airlines, and Pan American World Airways.

The 1980s and 1990s were tumultuous, as the airline industry was deregulated, labor costs remained high, and new, more cost-effective airlines rose up. American continued to innovate, including the industry-leading AAdvantage frequent flyer points program. The company survived this era, and in 2018, the latest full year for which figures are available, revenues of the now-named American Airlines Group were $44.5 billion, just edging out Delta to be the largest passenger airline in the world. (FedEx is the largest airline, with revenues of $65 billion.) American flies to 190 destinations in 55 countries. The company’s primary hub at the Dallas–Fort Worth airport, where American serves 500,000 people each day, continues to be one of the world’s busiest. The company employs about 130,000 people, a long way from the times when CR Smith could know every person at American.

Gary Hoover

Source: This story is primarily based on the 1985 book Eagle: The Story of American Airlines, by Robert Serling. The best books on the history of the US airline industry are Airlines of the United States since 1914 and Airlines of the Jet Age: A History, both by R.E.G. Davies.

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.