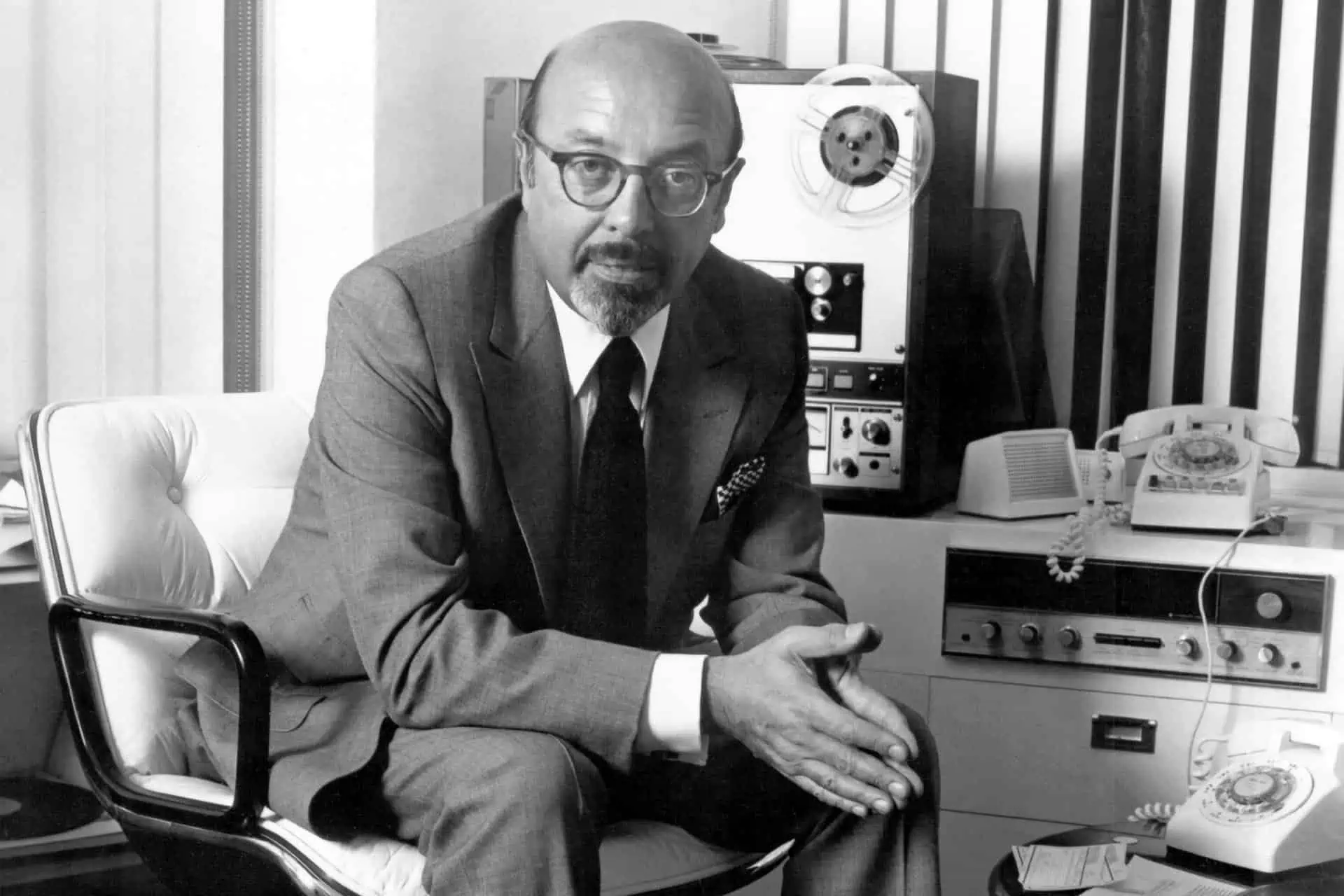

Ahmet Ertegun did as much as anyone to shape the popular music that serves as the soundtrack for our daily lives. As the founder and leader of Atlantic Records for almost sixty years, he brought us artists from Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin to Crosby, Stills, Nash, & Young; from Eric Clapton to Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones. He mentored and gave voice to rising record producers including Jerry Wexler, Phil Spector, and David Geffen. At the age of eighty-three, he fell and hit his head while backstage at a Rolling Stones concert, dying a few weeks later. Tears rolled down the cheeks of the most famous artists in the world at his memorial service.

Ertegun was in many ways the ultimate “foreigner” and perhaps seems an odd choice for this American Originals series of biographies. Born and buried a Turkish Muslim, he arrived in the United States as a pampered ten-year-old. At the age of thirteen, he was “the only white guy” backstage at Harlem’s nightclubs. In his segregated hometown of Washington DC, he was not supposed to be seen in public with his friend, composer Duke Ellington.

Ahmet rebelled against all that, struggled to get into business, and went on to become the greatest “record man” in the world. Yet, despite being an outsider, his story could only take place in the freedom and entrepreneurial environment of his adopted land, America. And no one loved American music as much as Ahmet Ertegun. This is his story.

Track One: Background

Ahmet Ertegun was born Ahmet Munir in Istanbul, Turkey, on July 31, 1923. (The family name, Ertegun, was not chosen by his father until 1936 when Turkish laws required every Turk to adopt a new, more “Turkish” surname.) To understand the man, we must first know his father, Mehmet Munir.

Early in the twentieth century, Mehmet Munir used his law degree to join the government of the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, where he soon became a top legal advisor. When the Istanbul-based empire was beaten and broken up by the Allies in World War I, a new rival to the empire arose: Mustafa Kemal, known as Ataturk, with his nationalist movement to create a new Turkey out of the rubble. Ataturk’s forces established their capital in Ankara, away from the Sultan’s seat of power in Istanbul.

The Sultan sent a delegation of his top emissaries, including Mehmet, to meet with Ataturk and try to resolve their differences. Not only were they unsuccessful is dissuading Ataturk from his ambitions, but they were also held captive for weeks by the nationalists and not allowed to return to Istanbul. Unlike his colleagues, Mehmet became convinced that Ataturk held the future of Turkey in his hands, and he “switched sides.” With his diplomatic skills and knowledge of international affairs, Mehmet Munir soon became one of Ataturk’s most trusted legal and diplomatic advisors as a new Turkey was created.

After lengthy negotiations, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed on July 24, 1923, ending the Ottoman Empire and creating the republic of Turkey. At Lausanne, Mehmet Munir was Turkey’s chief translator and legal advisor; seven days later, Ahmet was born. When the child was two years old, the family left Turkey: Mehmet had been appointed Turkish ambassador to Switzerland (1925). Transfers to France (1931) and the United Kingdom (1932) followed, giving young Ahmet exposure to the power centers (and powerful people) of Europe. His parents met the kings, queens, and prime ministers of Europe in their service to the new Turkish republic.

While living in London, Ahmet saw Duke Ellington in concert at the Palladium, an event which thrilled the nine-year-old and changed his life forever.

Track Two: Arriving in America, Crossing Boundaries

The next year, 1934, Mehmet was appointed ambassador to the United States, a position he would hold until his death in 1944. Eleven-year-old Ahmet was amazed by what he saw from his first-class suite as their ship arrived in the port of New York, though he did not see the cowboys he expected in America. (His strict British nanny had told him Americans were ruffians and savages.) Eager to impress the world, the Turkish government bought one of the most fabulous mansions in Washington, on Sheridan Circle overlooking Rock Creek Park, for the ambassador’s residence. It had been built for Edward Hamlin Everett, the “Bottle King.” The Turkish government paid $400,000 (about $8 million in 2021 money), one hundred times the price of the average American house.

Ahmet, his brother, Nesuhi (older by seven years), and their sister, Selma, were raised in the lap of luxury, replete with sixteen servants and cooks and two limousines with chauffeurs, who took them everywhere they needed to go. Because of his important position, Ahmet’s father was admitted to the Chevy Chase Country Club, an oddity given that the Erteguns were Muslim at the same time that the club would not admit Jews.

Above all else, Ahmet and Nesuhi fell in love with American jazz and blues. They attended Washington’s jazz clubs and began collecting all the records they could find. The boys went to the biggest record store in town. When they asked for Louis Armstrong records, the lady there told them, “We don’t have those. If you want those kinds of records, you will have to go to the n—– part of town.” Their regular hangout soon became Waxie Maxie’s record shop, where they could buy three records for a quarter and were among the very rare number of white people to visit. Over time, the brothers assembled a collection of over twenty thousand jazz and blues records, earning the teens an article in Esquire magazine. Even in his eighties, Ahmet could tell you every recording session and every musician on the black records of the era.

Ahmet received an outstanding classical education, excelling in math and history. At first he attended St. Alban’s elite private school, until his devout Muslim father pulled him out when the headmaster required Ahmet to attend chapel and take Christian religious instruction. At his next stop, the Landon School, no such classes were required, but “the religion of the school” was American football. With their European sensibilities, Ahmet’s family considered the sport brutal, and would not allow him to participate.

So, while the other students practiced football, Ahmet snuck off to skid row, unbeknownst to his family, seeking the music he loved. With his prominent forehead, buck teeth, and thick glasses, Ahmet looked like a bookworm, not a hipster, and must have seemed far out of place. His English accent, acquired in London, soon merged with the language of the black streets. His explorations grew with the help of the embassy’s black janitor, Cleo Payne. He was often the only white person at the Howard Theatre, where he saw all the top black acts in the nation. He was soon hanging out with the strippers backstage at the Gaiety Burlesque Theater.

In 1936, Ahmet’s father let the thirteen-year-old visit New York City along with a visiting Turkish Air Force commander. Upon arrival in Gotham, the officer headed to a meeting while Ahmet told him he wanted to go see a movie. Instead, the youngster hopped in a cab and said, “Take me to Harlem.” When Ahmet was nowhere to be found late that night, the police went looking for him. But the kid was smoking marijuana for the first of many times in his life, with a chorus girl at a Harlem rent party full of musicians. When Ahmet finally showed up, he was rushed back to Washington, where his normally reserved but distraught father slapped him for the only time.

By the time he was sixteen, Ahmet had become not only comfortable with being and appearing “different,” he embraced it. He grew a pencil-thin mustache, plastered his thin hair down, carried a mother-of-pearl cigarette case, and wore zoot suits like a “hepcat,” Cobra skin shoes, and a gold tie pin with rubies for eyes. Ahmet had begun to “invent himself,” a process that continued for the rest of his life.

The next year, the seventeen-year-old entered St. John’s College in Annapolis, where the emphasis was on studying the classics, mastering a new language every year, and independent thought. He developed a love for great literature and became fluent in Greek, Latin, German, and French. But when he (not infrequently) argued with his big (and more handsome and athletic) brother, Nesuhi, the language was Turkish.

In 1940, Ahmet and Nesuhi began to invite the top black musicians to the embassy for Sunday lunches, followed by jam sessions that went on through the afternoon. The Sunday jazz lunches became a weekly event. After one of them, Ahmet’s father, Mehmet, received a letter from a senator from the south which read, “It has been brought to my attention, Sir, that a person of color was seen entering your house by the front door. I have to inform you that in our country, this is not a practice to be encouraged.” Mehmet Ertegun sent a terse reply, “In my home, friends enter by the front door—however we can arrange for you to enter from the back.”

The only restaurant where Ahmet was allowed to bring his black friends was the one in Washington’s Union Station railway terminal.

By 1942, the brothers started promoting concerts of their favorite music for integrated audiences at those few places which would allow them, starting with a Jewish Community Center. Other venues only let them in when they threatened to make a ruckus in the newspapers. Nesuhi also began to give lectures about jazz in bookstores. Through these events, the brothers met other jazz and blues enthusiasts, some of whom developed business relationships with the Erteguns later in life.

Ahmet and his family continued to live a life of luxury and importance. Cary Grant and his wife, Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton, spent over a week staying with the family. Ahmet’s mother and the three children drove to California where they met Fred Astaire, Clark Gable, and Rita Hayworth.

Mehmet played a key role in convincing the Turkish government not to side with the Axis powers in World War II, earning the respect of the US State Department. The family had a German butler who was thought not to speak Turkish. But when he laughed at one of Mehmet’s jokes in Turkish, he was revealed as a spy and fired. In 1944, Mehmet Ertegun was named “Dean” of the Washington diplomatic corps because he was the longest-serving ambassador.

The year 1944 was one of the most eventful in young Ahmet’s life. In March, he graduated from St. John’s College with honors and then began graduate courses in medieval philosophy at Georgetown University. But on November 11 of the same year, Mehmet Ertegun died of a coronary thrombosis at the age of sixty-one. Held in Washington until the war ended, in 1946, Mehmet’s body was carried back to Turkey on the USS Missouri on the orders of President Truman.

For his entire life, Ahmet Ertegun and his family had lived the high life in a huge mansion, courtesy of the Turkish government. Now, that all came to a sudden end, with his mother moving into a small apartment and selling family possessions to pay off debts. She and Selma soon returned to Turkey, while Ahmet and Nesuhi stayed in the United States. Ahmet and Nesuhi were now on their own; a situation for which life had not prepared them.

Track Three: The Record Man

Twenty-one-year-old Ahmet Ertegun had no marketable skills and no real idea of what he wanted to do in life. He and Nesuhi sold their record collection to have money to live on. Ahmet tried to survive on the $100 per month student allowance provided by his father’s pension. The postwar economy was booming, but Ahmet was not ready to take just any job. Washington Post owner Eugene Meyer offered him a job at $20 per week, but Ahmet told him his allowance was more than that. He turned down the entreaties of friends on Wall Street to accept their job offers.

Ahmet continued his graduate studies and freeloaded off friends, moving from apartment to apartment. He lived on canned fish and bread, all he could afford. Nesuhi moved to Los Angeles to run a record shop, sending his younger brother $30 a month to help out. After a short stint selling insurance for a fly-by-night company, Ahmet Ertegun decided that he wanted to be in the record business.

The man had an ear for music and could memorize a tune he heard only once. He was an expert on gospel music, the Delta blues, and the Texas blues. He said, “In loving America, I felt I knew more about America than the average American knew about it.” He had bought a lot of records, hung out in record stores, and met most of the independent record producers. Many were “crooks and jukebox operators” who knew little about music. Ahmet later said, “I figured if they could make it, I certainly can.”

He thought he could work a day a week and spend the rest of the time on his graduate studies or enjoying music. But “it never occurred to me how a record came to be in a shop.” Ahmet knew nothing of record production, pressing, or distribution—nothing about the business of records.

To fill these gaps in his knowledge, Ahmet soon linked up with Herb Abramson, who was seven years older. Herb, though trained as a dentist by the army, shared a love of jazz and blues. He had worked for an independent record label, learning how to record and press records, as well as the ins and outs of artists’ royalties, contracts, and selling and distribution. After a few aborted attempts to get a record business off the ground, on December 31, 1947, Ahmet and Herb founded Atlantic Records, along with Herb’s wife, Miriam. To fund the venture, Ahmet’s dentist, Dr. Vahdi Sabit, put up $10,000 by mortgaging his home. Ahmet’s friends and family thought the idea was too risky, but Dr. Sabit, who owned 51 percent of the company, was willing to gamble on the two young entrepreneurs.

The partners picked the name “Atlantic” after their “about eighty” first choices were rejected because the names were already in use by other record labels. Even today there are thousands of record labels owned by hundreds of companies.

Herb Abramson was made president of the new company, owning 30 percent compared with Vice President Ahmet’s 19 percent, though half of profits were split evenly between the three owners, the other half divided in proportion to their shares of stock. Herb and Ahmet were each paid $40 a week to cover their expenses. For another $60 a week, they rented a two-room suite in a run-down hotel in midtown Manhattan. Ahmet slept in one room, shared with his poet cousin.

Even when at his financial lowest, Ahmet did not (perhaps could not) adjust to normal life. He had been pampered since birth. A friend was visiting when Ahmet complained that he had no shirts to wear. The friend saw stacks of dirty shirts in the closet, asking Ahmet, “Have you ever heard of a laundry?” He didn’t pay his bills, because “Gentry didn’t do that.” He spent every penny he got his hands on, including money his mother sent him, now wearing expensive alligator shoes. But with all his weaknesses, Ahmet had some rare and valuable skills: he could talk to anyone, from the janitor to royalty. And he was as good a diplomat as his father had been. (For many years, he considered Atlantic Records a temporary affair, planning to return to Turkey and become a diplomat, though that idea faded over time.)

Ahmet also spent every night out on the town, a routine that continued for the next six decades. Living in New York City, his shyness around women soon disappeared. Friends said that for him, “Hell was having to go home early.” He could “drink anyone under the table.” Everyone who ever met the man said, “Ahmet was a lot of fun.”

In the first five weeks of Atlantic’s operation, Ahmet and Herb spent $3,000–4,000 recording sixty-five record “sides,” trying to beat a pending musicians’ strike, but all “went in the trash.”

Yet by 1949, the (barely) two-year-old company had made a few minor hits, was selling forty thousand records a month, had twenty-six distributors across the country, and was ranked the twenty-fifth largest company out of five hundred of those producing “race records.” (A journalist at Billboard magazine named Jerry Wexler convinced the magazine to change the term to “rhythm & blues.”) Ahmet “was working harder than he ever had in his life,” staying out until 1 a.m. every night, looking for talent. Herb oversaw making the recordings and Miriam was the business manager, hounding distributors for payment. While the three took out small salaries, most of the cash was reinvested in the business.

Track Four: The First Hits and Stars

Atlantic’s first real hit came in 1949. “Stick McGhee” had recorded “Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee” on two small record labels, but the records were in short supply. Atlantic’s New Orleans distributor told them that he’d buy five thousand copies if Atlantic could provide them. After spending twelve hours in the studio to “get it right” and paying McGhee $500, the record hit #2 on the jukebox chart and #26 on the pop chart. Atlantic sold seven hundred thousand copies, and bootleggers perhaps a million more. (Ahmet wanted to confront a major bootlegger but changed his mind when he learned that their Texas record plant was protected by five or six armed men.)

Ahmet, Herb, and Miriam soon learned that they needed to keep generating hits in order to get the distributors to pay their prior bills. Signing new artists and making hits became the hallmark of Ahmet’s career and thus of Atlantic Records, even though in the early years Atlantic could not pay musicians as much as the big record labels including Columbia and RCA Victor. The diplomat, Ahmet, had to romance each artist and truly care about their music and the quality of the recordings.

In order to discover new talent, Ahmet and Herb hit the road. In the spring of 1949, they made a long tour of the South, putting ten thousand miles on a borrowed Ford convertible that they had agreed to deliver from New York to Texas. After finding artists in Atlanta, they visited New Orleans.

With their ear to the ground, they were told to go to Algiers, Louisiana, across the Mississippi River from New Orleans. Crossing the river by ferry, at eleven at night they arrived near Algiers, where their taxi driver refused to drive into “that n—- town.” The two men slogged across a muddy field to find a shack that was rocking with a loud band. Ahmet said it looked like one of those animated cartoons in which the building swung with the music. The guy at the door took convincing to let them in, since everyone assumed they were “the law” as nobody had seen white people at the joint before. Once inside, they found a solo piano player with his foot hooked to a bass drum, a fellow named Professor Longhair playing “gutbucket” blues. He cut a couple of records for Atlantic, but they were not hits, though he later went on to fame.

The first star for Atlantic was rhythm & blues (R&B) songstress Ruth Brown. Ahmet, Herb, and Miriam worked hard to introduce her to new tunes and take her to clubs to hear the music of others. Between 1949 and 1961, she cut nearly one hundred sides for Atlantic. Five of them hit #1 on the R&B chart; eight more made the top ten. Her first number one hit was “Teardrops from My Eyes” in September 1950. By 1955, the company had sold more than five million of her records. Normally she was paid $70 for a side, but up to $250. For live performances, she was earning $750.

In 1948, Atlantic had been the twenty-fifth biggest R&B record company. From 1951 onward, the company was the undisputed number one in the field, and the industry began to talk about “the Atlantic sound.” The company also produced jazz, including artists like Dizzy Gillespie and Dave Brubeck, but the bills were paid by their R&B record sales.

The team expanded by adding writer and arranger Jesse Stone and engineer Tom Dowd, both wizards in music production. Atlantic records included early “crossover” hits, with soulful music from Clyde McPhatter, Ruth Brown, the Clovers, the Coasters, and the Drifters appealing to white teenagers. By 1953, the business was successful enough that Ahmet gave up his dreams of returning to Turkey, becoming a permanent resident alien and later a United States citizen.

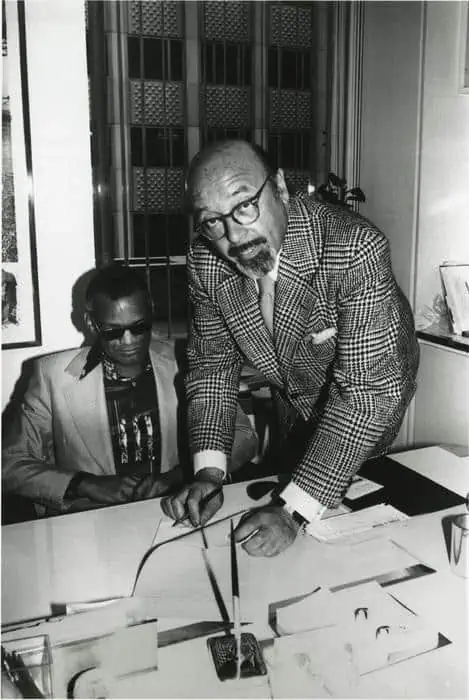

The biggest event of these early Atlantic years was the 1952 signing of Ray Charles for $2,500. But it took a lot of work with the difficult artist before his genius would reach mass audiences.

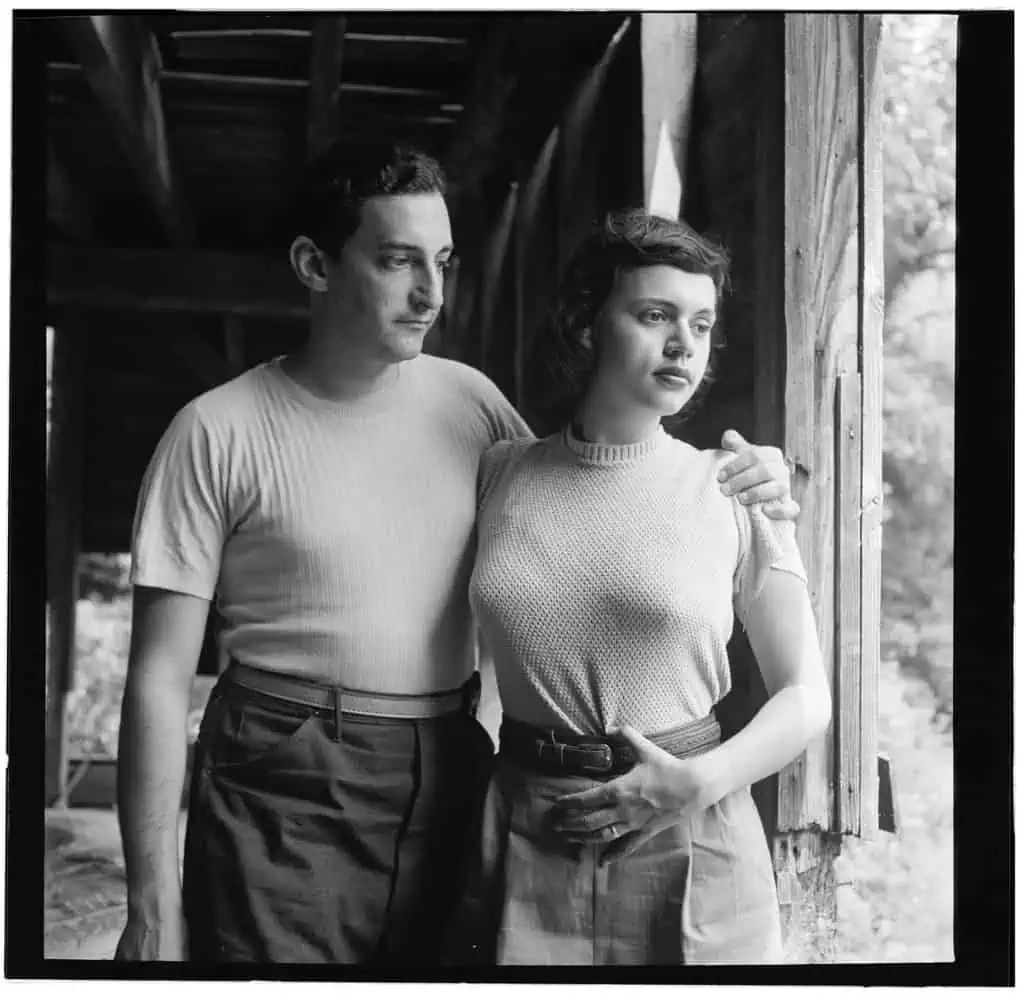

In 1953, twenty-nine-year-old Ahmet married Californian Jan Holm. His friends were married, and “it seemed like the thing to do,” but the marriage was not meant to be. They were amicably divorced two years later.

Track Five: Changing of the Guard

Also in 1953, the army called on Herb Abramson to serve the active duty time he owed them for his dentistry training. He spent the next two years in Germany. Ahmet and Miriam were worried: they did not have all the skills and industry knowledge that Herb brought to Atlantic.

When the team got the news that Herb was leaving for active duty, they made that Billboard reporter named Jerry Wexler a minor partner. Wexler invested $2,063 for a 13 percent interest in the company. Ahmet immediately used the money to make a down payment on a Cadillac convertible, giving it to Wexler “to be seen in.” (No matter their financial situation, Ahmet always placed a high priority on a “veneer of prosperity.”)

Wexler loved black music as much as Atlantic’s founders. He and Ahmet were both considered “walking encyclopedias of jazz and blues.” Jerry’s personality was as unique as Ahmet’s: he was a tireless—almost manic—workaholic, arriving early and staying late. By his own admission, he didn’t believe anyone else at the company knew what they were doing and was incapable of delegating. His mother and brother were Communists and Jerry was an intellectual. But he was also powerfully built, looking “like a dockworker,” profane, and “never walked away from a fight.”

Ahmet and Jerry formed a partnership. Ahmet defined “cool;” no one was “hotter” than Jerry. Ahmet was “Mr. Outside,” representing Atlantic to the business world; Jerry was “Mr. Inside,” working with the artists to produce hit records. For the next twenty-two years, this unusual team produced some of the greatest music America (and the world) has ever heard.

Doing their own version of Ahmet and Herb’s road trip, the two hit the highway and headed south. As they sought out new talent, they partied hard and “had a lot of fun.” The practical jokes and stunts were endless. Everywhere they went, they would act out little “playlets” in which Ahmet would make fun of Jerry, who would play the moronic straight man. They found more talent. They almost snagged Elvis Presley, but RCA’s offer of $45,000 topped Atlantic’s $30,000 (which would have been hard for Atlantic to come up with).

The pair’s first hit was Big Joe Turner’s “Shake, Rattle, and Roll.” In April 1954, it went to #1 on the R&B chart and stayed there for eleven weeks. A cover version by Bill Haley and the Comets (not on Atlantic) went on to sell over a million copies.

Jerry Wexler started working with Ray Charles, who had not yet had a breakthrough hit—at least not until December 1954 with the release of the #1 hit “I Got A Woman.” Many consider Charles’s blend of blues and gospel to be the beginning of “soul music.” Atlantic’s hits continued to appeal to the white teens known as “bobbysoxers.”

In this era, Atlantic also recruited Ahmet’s brother, Nesuhi, to join the company, heading up their jazz division. Nesuhi was the most respected jazz expert in the recording industry. While jazz was not a big moneymaker, Ahmet thought it important that they “keep jazz alive.” Important Atlantic jazz artists included John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Charles Mingus, and Thelonious Monk.

In April 1955, Herb Abramson returned from the army to re-assume his role as president of the company. But by then two things had changed. One change was Herb himself, who returned with a German girlfriend and divorced key partner Miriam, acted “a little nuts” according to friends, and may have become addicted to cocaine while doing dentistry. And the other was that Jerry Wexler was running the studio and had become tight with Ahmet.

Founder Herb Abramson was now “on the outside,” a situation which could not last. As part of their divorce, Miriam got about half of Herb’s 30 percent ownership in Atlantic. Ahmet decided he should be president and Jerry and Herb vice presidents. Herb could not accept the change, and Nesuhi, Ahmet, and Miriam bought him out for $300,000 in 1958, at which point co-founder Herb Abramson left Atlantic.

Before Herb left, he had signed a young artist named Bobby Darin. With no successful records, Herb decided to release Darin from his contract, but Ahmet saw talent in Darin and kept him. Atlantic released Darin’s “Mack the Knife” in August 1959. The record stayed in the top ten for a year, selling two million copies and winning Atlantic’s first Grammy Award, for record of the year and best new artist. Darin’s “Splish Splash” and “Yakety Yak” by the Coasters were also hits for the company.

Ray Charles also made his first gold record (million seller) in 1959 with “What’d I Say.” By year’s end, he had been lured away by upstart ABC Records, the effort of the American Broadcasting Company to enter the record business. ABC offered him a guaranteed $50,000 per year and 75 percent of the record revenues. Even more extreme, Charles would get back the master recordings after five years, allowing him to re-issue the records on his own, unheard of in the industry. Though Atlantic was unable to match this offer, Ahmet thought that Ray would stay with Atlantic out of loyalty.

Ahmet took Charles’s “betrayal” hard and personally. It was said that he was brokenhearted and never had the same affection and relationship with another artist after he lost Ray Charles, although Ahmet certainly gave more affection, care, and feeding to his artists than almost any other record producer. Discovering, signing, and losing talent are part of the record industry, and Ahmet and Atlantic learned to live with that fact of life.

In the late 1950s, the “payola” scandals hit the record business. Record labels had been paying radio disk jockeys (DJs) cash under the table to play their records for years. Prominent DJ’s like Alan Freed, for whom Atlantic had built a home swimming pool, were arrested. Atlantic was able to emerge from the headlines unscathed, though the company had paid for play like the other labels, but perhaps not as egregiously.

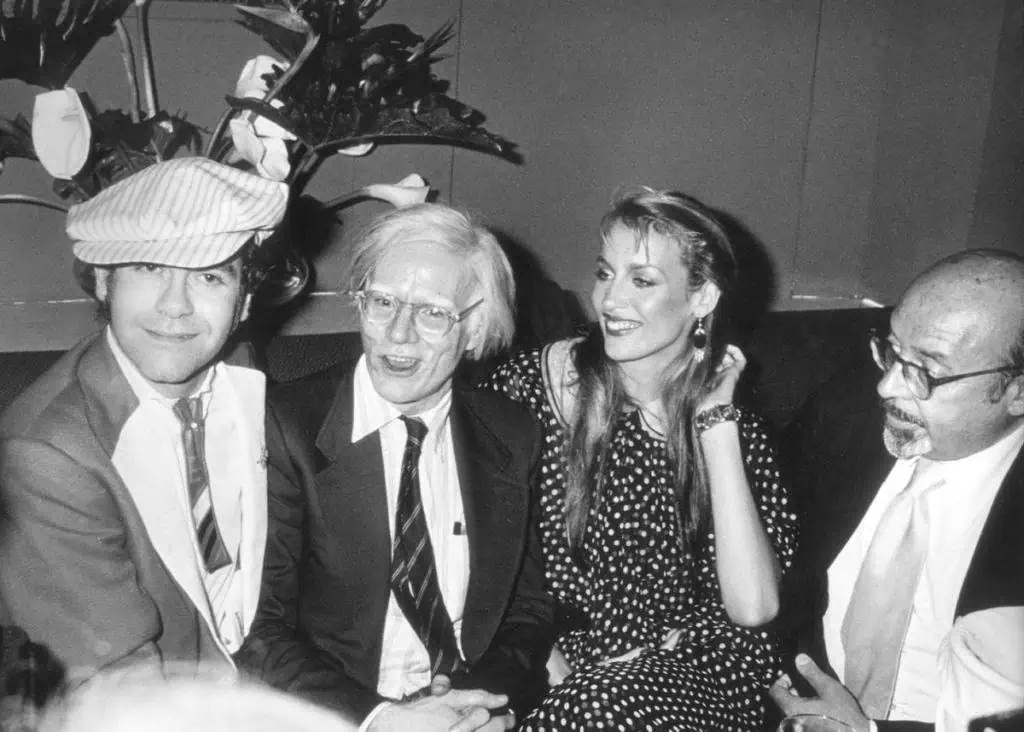

Throughout these changes, Ahmet continued to evolve his image, dressed to the nines, and went out nightly to Manhattan’s toniest nightclubs with models on his arms. Having gotten too many parking tickets, he bought a used Rolls Royce and paid a retired Irish cop seventy-five cents an hour to chauffeur him. Esquire magazine named him one of America’s best-dressed men. Ahmet hung out with Cary Grant, Marlene Dietrich, Andy Warhol, and members of the wealthy Astor and Vanderbilt families. His efforts succeeded: while he had less than $10,000 to his name, the newspaper society columns referred to him as “the Turkish millionaire.”

Track Six: Going to the Next Level

In 1960, twenty-one-year-old Phil Spector became Ahmet’s next “trainee.” Spector served as Ahmet’s personal assistant and slept in the Atlantic office. He considered Ahmet a “father figure.” For a while, Ahmet and Phil were inseparable, hanging out at clubs together. (Ahmet often hung out with much younger people, perhaps because only they could keep up with the pace of his nightlife.) The two roared down Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles at 90 mph in a Ford Thunderbird with a record player installed under the dashboard. Even “crazier” than the other characters in this story, the extremely difficult Spector became a brilliant record producer.

Phil Spector’s education under Ahmet only lasted until the spring of 1961, after which Spector left Atlantic to create Phillies Records and make many hit tunes. He was a multimillionaire by twenty-six and later worked with artists ranging from Ike and Tina Turner to the Beatles. Spector produced the Beatles album “Let It Be.” One of Spector’s many eccentricities was that he hated being abandoned, to the point where he would lock visitors in his house and not let them leave, sometimes waving a gun around. In 2009, he was convicted of the 2003 shooting death of actress Lana Clarkson at his home. Phil Spector died in prison at the age of eighty-one in January 2021. Despite all these issues, Spector and Ahmet remained friends.

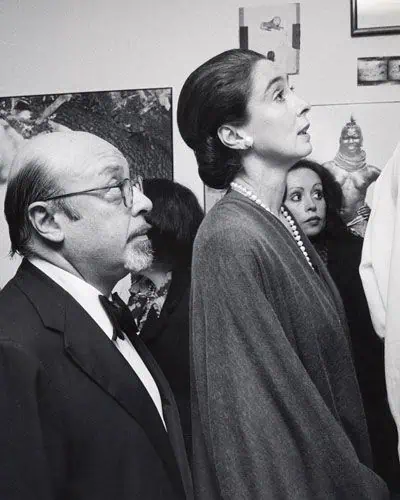

In this same short period, Ahmet met the love of his life, Iona Maria “Mica” Banu, a sophisticated Romanian woman three years younger than he. They were married in April of 1961 and remained so until death did them part. (Ahmet’s sexual appetite was legendary. But Mica had a “European attitude” toward his many infidelities and dalliances, and after his death said, “He was always there for me” but that “Ahmet liked to have fun. I am sure he did a lot of naughty things.”)

Atlantic’s string of successes came to a halt in 1964, resulting in the first annual decline in profits in the company’s history. That February, a British band called the Beatles appeared on the Sunday night Ed Sullivan Show, and everything changed. “The bottom dropped out” of the white teen demand for black music while Motown rose up to absorb whatever demand there was. While Jerry Wexler wanted to continue the focus on black music, Ahmet’s priority was making hits, pursuing whatever the market wanted.

In 1964 alone, the Beatles produced six LP’s and nine singles, selling twenty-five million records, by some estimates 60 percent of all the records sold in America. Ahmet fired the company’s long-time lawyer for not bringing Atlantic the Beatles, who were working with that same lawyer on their American rights. The attorney never bothered to tell Ahmet that he had in fact offered the Beatles to Jerry Wexler, who found them “derivative” and of no interest to Atlantic. The Beatles instead signed with small Chicago label Vee-Jay, which soon enough went bankrupt because the head man had a gambling problem.

Over time, Ahmet and Jerry drifted further apart. Mica became the most important person in Ahmet’s life. Ahmet loved the high life, appearing with stars and the wealthy, whereas Jerry had no use for all that. Ahmet looked for hits; Jerry was stuck on the blues. And while Ahmet believed in the future of Atlantic Records, Jerry Wexler was “always nervous” about the future, concerned that their “luck would run out.” Most of the other independent record companies had crashed and burned. A year or more without a hit meant doom. The industry was so fickle. Jerry had conversations with other companies about merging or selling out without telling Ahmet, further eroding their relationship.

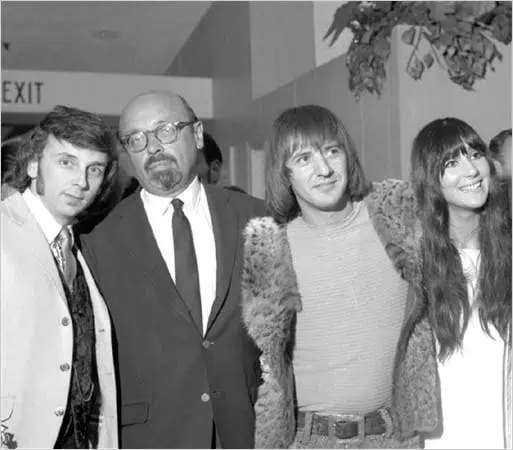

While Jerry Wexler continued to produce great black music, Ahmet was on the lookout for potential hits, no matter what type of music. He heard a couple on Los Angeles radio. While he was not enamored of their music, he knew that teens liked love songs and rebellion and he had an ear for hits, so he signed Sonny and Cher. Their song “I Got You Babe,” released in mid-1965, became Atlantic’s first worldwide million-seller. (Jackie Kennedy asked for the two to perform at a dinner party and Ahmet arranged it.)

Ahmet gave Sonny and Cher’s agents a $100,000 bonus, and those agents soon brought Atlantic another act that was performing live and wowing crowds in Los Angeles: Buffalo Springfield. (Jerry Wexler had rejected the group because he hated “pop acts.”) A rare group with multiple great singers and talented guitarists, the combination of ambitious Stephen Stills, loner Neil Young, and Richie Furay had a big hit for Atlantic in the spring of 1967, “For What It’s Worth.” (Buffalo Springfield bassist Bruce Palmer said about their agents, “Greene and Stone were the sleaziest, most underhanded, backstabbing mother—-s in the business. They were the best.”)

Stephen Stills saw Ahmet as a father figure, and even copied his goatee and expensive clothing. Despite Ahmet’s extreme efforts to keep the group together, they broke up the next year, but Ahmet and Atlantic continued their relationship with Stills, Young, and later Graham Nash and David Crosby.

Atlantic had other big successes at the time, including Otis Redding’s “Dock of the Bay,” released after Redding was killed in an airplane crash. (Otis always called Ahmet “Omelet,” assuming he liked eggs, and referred to Nesuhi as “Nescafe.”) The company also released Iron Butterfly’s “In-A-Gadda-da-Vida,” which they said would be impossible to cover because it would be hard to find a drummer that bad—he dropped his sticks in the middle of the recording. Other winners were Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” and “Groovin’” by the Young Rascals. In June of 1967, Atlantic had eighteen records in Billboard’s “Hot 100.” The company’s profits doubled in 1967 compared with 1966.

In 1967, Ahmet and Nesuhi also helped found the Montreux Jazz Festival in Montreux, Switzerland, which went on to become one of the most prominent such events in the world.

Track Seven: New Bosses, New Artists

Jerry Wexler continued to worry about the future of the company. He said, “I had this feeling that a puff of wind could come along and blow us all away, instantly.” As the company grew, Ahmet had bought out Miriam’s ownership share for $600,000 as well as Dr. Sabit’s share. (The good dentist made $2–3 million on his $10,000 investment, between dividends and selling his shares.) This made Ahmet the largest partner, perhaps with a majority, but even so, Jerry and Nesuhi, who both wanted to cash in, had sway with Ahmet. Despite their differences, Ahmet recognized Jerry’s talent and felt Atlantic could not afford to lose him. This led to negotiations with a company named Warner Brothers-Seven Arts in 1967.

Seven Arts was a small film production company which made most of its money distributing television programs and movies to TV stations. Earlier that same year, Seven Arts had bought the troubled Warner Brothers movie company from Jack Warner for $32 million. One of Warner’s more valuable assets was Reprise Records, which Warner had bought from Frank Sinatra a few years earlier. Thus the record business was important to Warner Brothers-Seven Arts at the time they began discussions with powerhouse Atlantic. In order to help convince Ahmet to sell out, Sinatra hosted a party as his apartment. The new owners promised Ahmet and Jerry that they could continue to “run their own show.”

Thus, in late 1967, Atlantic Records was purchased by the Warner Brothers-Seven Arts Company for a total of about $17.5 million including cash and stock in Warner-Seven Arts. Jerry Wexler’s share was $4 million, giving him the security he had long sought. Many consider this one of the worst deals in entertainment history, at least from the viewpoint of the sellers. In 1968, Atlantic’s profits doubled for the second year in a row, on record revenues of $45 million. Ahmet offered to buy back Atlantic for $40 million, but Warner-Seven Arts was not interested in selling.

In the midst of these changes in corporate structure in the late 1960s, Ahmet kept Atlantic moving ahead. When he heard just one half of one track of a demo tape by David Crosby, Stephen Stills, and Graham Nash (CSN), Ahmet handed their producer a blank check, saying “Fill in the number. I don’t care what it is, it doesn’t matter.” (Ahmet was now playing with other people’s money, not his own, increasing his generosity and ability to bid for talent.) Atlantic lured CSN away from their arch-rival, legendary CBS/Columbia Records chief Clive Davis.

With CSN came their new agent, the “immensely ambitious” David Geffen, then in his mid-twenties. Jerry Wexler had thrown Geffen out of his office—even CSN called him “a shark.” But Ahmet was savvy enough to “seduce” Geffen, who soon became Ahmet’s new protégé. Geffen said, “There was nothing I would not have done for him.”

Graham Nash said, “Every time he [Ahmet] walked into a room, it didn’t matter who else was there. Elvis could have been there and everyone would have been looking at Ahmet. It was very obvious when he walked into a room that this was a mighty, mighty presence.” Nash also said that “no record guy” ever got along with the artists as well as Ahmet.

At Ahmet’s urging, CSN added Neil Young, despite his conflicts with Stills, and soon became Crosby, Stills, Nash, & Young (CSNY). Their albums including Déjà Vu became big hits. Ahmet went to great lengths to keep them together, but the personalities were too combustible, and they did not last as a group. Ahmet remained friends with the individual artists, continuing to produce some of their solo efforts.

Now trotting the globe in search of talent, Ahmet settled into a luxurious hotel suite in London. Working with fellow producer and friend Robert Stigwood, Ahmet got the American rights to the Bee Gees. He also attracted the Spencer Davis Group with Steve Winwood to Atlantic. British “supergroup” Cream, including Eric Clapton, and recorded their album Disraeli Gears in a few days at Atlantic’s New York studio.

The Bee Gees and Cream represented as much as 50 percent of Atlantic’s album sales at this time. Cream alone sold fifteen million albums in their three years together. Eric Clapton joined the many artists who “loved Ahmet.” (Later on, Ahmet made a special trip to try to convince Clapton to give up heroin, Ahmet having witnessed junkies destroy themselves and everyone around them.)

Ahmet also found time to get into the studio, often choosing which songs to record, what tempo to record them at, and arranging the parts and the mix (volume). He even made time to mentor yet another young producer, Jamaican Chris Blackwell, the founder of Island Records.

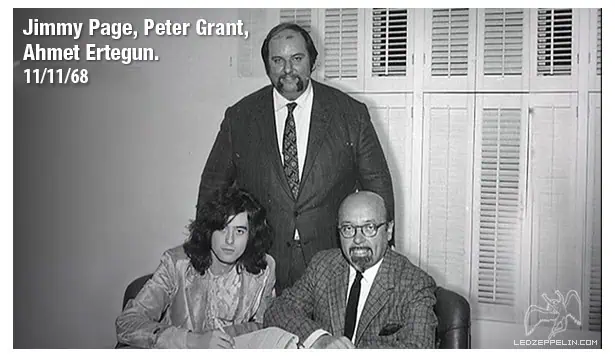

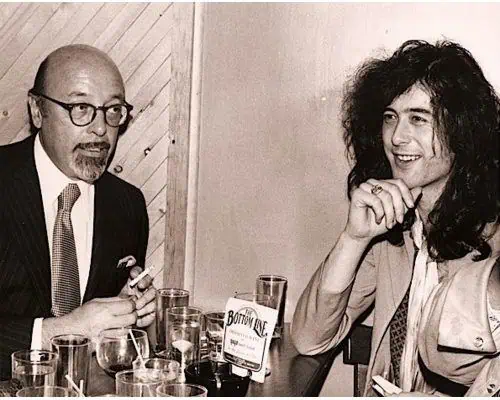

In an odd twist, it was Jerry Wexler who brought Led Zeppelin to Atlantic. (The group got their name when someone suggested their music would go over “like a lead zeppelin.”) Jerry knew Jimmy Page from his work as a top session guitarist. And unlike the early Beatles, whom Wexler had turned away, Page and Robert Plant incorporated the blues into their music. Jerry, however, continued to roam the South looking for black talent and turned management of Zeppelin over to Ahmet. Atlantic gave them a $75,000 advance for five albums and bought the world rights for another $35,000.

Led Zeppelin’s first album, released in December 1968, sold eight million copies in the US alone, and stayed in the top ten for seventy-three weeks. Their fourth album, including rock anthem “Stairway to Heaven,” sold 23 million. Over the next eleven years, the group sold 110 million albums in the US and more worldwide. Ahmet attended many of their concerts, which broke the attendance records set by the Beatles, and partied with the raucous band backstage and on their chartered Boeing 720 “Starship” jet. He, Page, and Plant became good friends. Robert Plant referred to Ahmet as “the master of serenity,” an oasis of calm in the storm.

As convoluted as the Warner-Seven Arts-Atlantic history was, the corporate ownership of Atlantic got even more complex in 1969. For that story, we must step back in time a little bit.

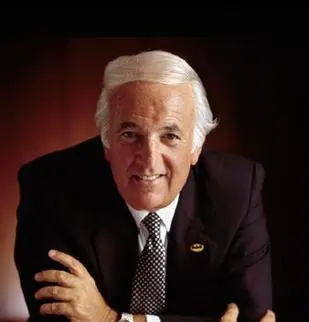

In 1953, Brooklyn-born Steve Ross married the daughter of the owner of New York City’s Riverside Memorial Chapel, the biggest funeral home in America. The ambitious Ross noticed that the company’s limousine fleet was only being used during the daytime and convinced his father-in-law to lease them out at night for other uses. Ross rose to take over the company, expanding into rental cars and buying a chain of New York City parking lots, Kinney Parking. Renamed Kinney National Services, the company went public in 1962, with a market capitalization of just $12.5 million. Ross, the ultimate wheeler-dealer and brilliant at creating complex financial deals, took the company into entertainment by buying the large talent agency Ashley Famous in 1966. In 1969, Ross bought Warner Brothers-Seven Arts, including Atlantic and Reprise Records, for $400 million. Ahmet planned on leaving the company until Ross convinced him otherwise, promising him independence and control of Atlantic. Three years later, the company was renamed Warner Communications.

Thus, in the short span of about two years, Ahmet found himself working for a much larger “entertainment empire.” History tells us that many entrepreneurs do not survive such shifts. But, as usual, the diplomatic (wily?) Ahmet not only survived but prospered in the new corporate environment.

While it is not clear that Ahmet and Steve Ross ever really liked or trusted each other, they were able to get along and make a lot of money together. While Ahmet was to (technically) report to different bosses in the coming years, he remained in the driver’s seat at Atlantic and an icon in the industry and with his beloved (and pampered) artists. On the other hand, Jerry Wexler hated the corporate environment and fought the directives from above at every turn.

Track Eight: Bigger and Bigger Under Warner Communications

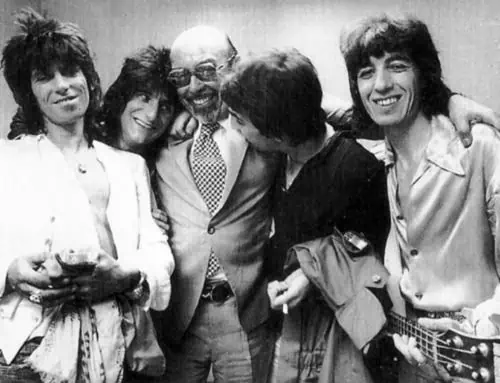

By late 1969, Ahmet had been courting the Rolling Stones for over a year. He shared a love of the blues with Mick Jagger. Mick wanted to sign with Atlantic, now considered THE label, but the graduate of the London School of Economics was also business-savvy and wanted the most money. Ahmet landed the band with an advance of a million dollars an album and a royalty of one dollar a copy, one of the most expensive deals up to that time. Atlantic sold three million copies of the Stone’s album Sticky Fingers, their most successful album to date, including the hit “Brown Sugar.” Their next album for Atlantic, Exile on Main Street, came out in May 1972. The concert tour for the album sold $3 million in tickets, a record. Ahmet, Mick, and the other Stones became close friends, as Ahmet threw big parties for them, including in the south of France.

Ahmet’s young protégé David Geffen wanted to have his own record label. His goal was to find singer-songwriters who created their own material. Ahmet helped him, with Atlantic owning 50 percent of the company and handling manufacturing, distribution, and promotion for the new company. Assuming his artists were “on the edge,” Geffen named his label Asylum, which began business in 1970. The first artists on Asylum included Jackson Browne, Joni Mitchell, Linda Ronstadt, and the Eagles. David Geffen later sold his half of Asylum to Warner for about $7 million.

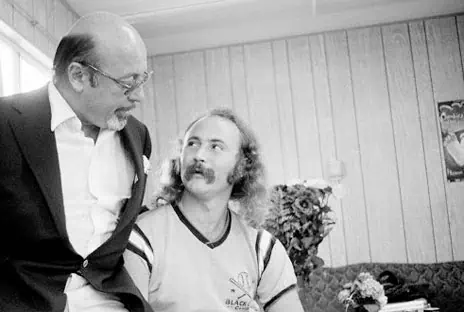

Ahmet also convinced his St. John’s College friend Jac Holzman to sell his Elektra Records (including The Doors) to Warner for $10 million. Holzman later said, “In many ways, Ahmet was a rug merchant” because he loved the game of negotiating. Geffen became head of the newly created Elektra-Asylum division of Warner. In his new role, Geffen lured Bob Dylan away from Columbia Records (temporarily). In doing so, he antagonized Jerry Wexler, who was also pursuing Dylan for Atlantic. In a poolside meeting of Warner’s top record executives (pictured below), with Warner chief Steve Ross present, Geffen and Wexler got into a name-calling match and had to be restrained. Ross had no patience for such internecine warfare. Wexler’s star was falling.

In the early 1970s, the record operations of Warner were key to the company’s profitability. In 1973, Atlantic generated $75 million in revenue with a 25 percent profit margin. Atlantic, Elektra, Asylum, and Warner Brothers Records had combined revenue of about $250 million. Steve Ross amply rewarded the record executives, especially Ahmet, with big cash bonuses and stock options. Their base salaries were set so high that no competitor could hire them away.

While titles and reporting structures continued to evolve, Ahmet was the “first among equals” because of his iconic industry status, ability to find and keep talent, make hits, and diplomatic skills in the boardroom. Others said, “Ahmet had a genius for staying in the middle . . . he’s never on the wrong side of anybody.”

He lived the good life, traveling in the Warner Gulfstream II jet, collecting the art of Jasper Johns and Henri Matisse, and being driven around town in two Cadillacs or his Rolls Royce or vintage Bentley. All his clothes and shoes were custom made, and he and Mica had homes in Manhattan (five stories), Southampton (Long Island), and Paris as well as a virtual palace in Bodrum, Turkey. The couple entertained their celebrity friends lavishly. When asked, “How do you know when you have really made it?” Ahmet answered, “When you no longer carry any keys.” Everywhere Ahmet went, someone was there to open the door.

In 1974, musician Frank Zappa named his newborn son Ahmet after him.

Later, David Geffen moved to the re-invigorated movie part of Warner and then left the company to start Geffen Records in 1980. He eventually sold that company for $550 million to Warner competitor MCA (ultimately named Universal Music Group).

In 1975, Wexler’s twenty-two-year run at Atlantic came to an end. The “cantankerous, abrasive, cynical” recording genius could not fit into the corporate environment. He was never a “team player.” Ahmet, on the other hand, used his diplomatic skills to negotiate and survive, no matter which way the winds blew.

In February 1977, Ahmet re-signed the Rolling Stones for five albums and a $7 million advance. The album Some Girls sold six million copies in America, including the hit “Miss You.” But the title song of the album contained the lyric, “Black girls just want to get f—-d all night.” Ahmet tried without luck to get the band to change the lyric. Their contract gave the Stones control of their songs’ content. Understandable outrage and protests ensued.

Black activist Jesse Jackson convinced Ahmet to come to Chicago and face an angry crowd, telling his side of the story. After a pre-agreed over-the-top rant against Ahmet by Jackson, Ahmet calmly explained that he had no control over the artists. The crowd took pity on Ahmet and he ended up with their favor. The ever-diplomatic Ahmet donated a million dollars to Jackson’s organization as part of the deal. While Atlantic eventually lost the Stones, the band stayed friends with Ahmet until the end of his life.

As Atlantic moved into the 1980s, Ahmet continued to find, promote, and mentor skilled record producers. While Ahmet remained chairman of Atlantic, others carried the title of president, running day-to-day operations. For several years, Jerry Greenberg played Wexler’s old role, then was followed by Doug Morris. Each went on to illustrious careers in the record industry. Morris said, “I learned the art of the business from Ahmet. I learned how to talk to people.” In his first year on the job at Atlantic, Morris produced five of the top ten selling records of 1980. Ahmet had Warner give Morris a $750,000 bonus on top of his $250,000 salary, then tossed in another $250,000 out of Ahmet’s own bonus.

At one point when Warner as a company was struggling—their acquisition of video game company Atari had turned sour, and the company lost over $400 million in one year—each division chief was called onto the carpet to report their plans to increase profits. As their meeting with Steve Ross approached, Doug Morris told Ahmet he was worried: what would they say? Ahmet told him not to worry; he would take care of it. As Ahmet waltzed into the meeting late, Ross and his top executives challenged him: what were his plans for the next year? “We’re going to make more hits,” answered the diplomat. That was enough for Ross; the meeting ended. And Atlantic delivered that year on Ahmet’s promise.

Now in his sixties, Ahmet could still stay out until four a.m. and then show up the next morning with a breakthrough idea. At other times, the aging leader would come into the office at four p.m. and leave at six, saying, “There’s a lot of work to do around here. Fortunately, I have people to do it for me.” Yet, due to Atlantic’s prosperity, Ahmet received salaries and bonuses running into the millions, as did his key lieutenants.

Under this system, Atlantic successes in the 1980s included Foreigner, AC/DC, Twisted Sister, Yes, White Lion, INXS, Genesis, and Debbie Gibson.

About Ahmet, prolific music writer Dave Marsh wrote,

I knew (famous producer) John Hammond, Jerry Wexler, and Sam Phillips (Sun Records), and I am here to tell you Ahmet was the greatest record executive who ever lived. He was more creative, he had wider taste, he kept himself in the game longer, he had the greatest rapport with the artists, and he made a market again and again and kept it. He did R&B, free jazz, hard rock, soul music, psychedelic rock, disco, and all that stuff in the 1980s and 1990s.

Ahmet and Nesuhi had always loved soccer and were instrumental in the formation of the New York Cosmos, owned by Warner. Despite recruiting famous star Pele and drawing big initial crowds, the team folded in 1986. Ahmet also played a critical role in creating the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland and its annual awards ceremony.

In 1988, Atlantic threw a big fortieth anniversary celebration. Originally it was scheduled for Radio City Music Hall, the nation’s largest theater, but the Hall could not hold the crowd and the event was moved to Madison Square Garden. Bill Murray, Michael Douglas, Henry Kissinger, and many others from Ahmet’s social circle attended to see Wilson Pickett and Ahmet’s good friend Phil Collins from Genesis, but the event of the night was a rare Led Zeppelin reunion performance.

In 1989, Nesuhi Ertegun died of cancer. While their relationship was at times contentious, Ahmet deeply missed his older brother.

Also in 1989, Steve Ross engineered the acquisition of magazine publishing giant Time, Inc., resulting in the formation of Time Warner, the renamed parent company of Atlantic.

In 1991, Ahmet’s latest boss at Warner offered the sixty-eight-year-old a lucrative contract. Elements included pay of at least $600,000 per year for five years, followed by half pay for another five; 115,000 stock options on top of those Ahmet already had, with a guarantee that he’d make at least $11.5 million on the shares; forgiveness of a $900,000 mortgage on Ahmet’s New York home; and a signing bonus of $2.5 million. All together, the package was worth at least $20 million (about $40 million in 2021 dollars).

Ahmet and Mica, who had her own interior design firm, MAC II, continued to collect art, traveling the world and discovering unrecognized artists, just as Ahmet had in the music world. The art overflowed their homes and was loaned to museums around the nation.

In 1992, Ahmet and Doug Morris went to the office of Steve Ross’s right-hand man and demanded more stock options and bigger salaries, equaling what executives in the movie part of Time Warner were getting. They got Steve Ross on the phone, who was dying of cancer at home. Ross stormed over the phone that they were fired and to get out of his office. When Ahmet and Doug left the office, Doug was worried: what are we going to do? Ahmet calmly replied, “Go to Sony (which had purchased Columbia Records) and create a new record label.” On their way to the Sony offices in a limousine, they received a call telling them that Steve Ross had acquiesced to their demands. Ahmet knew he held most of the cards. Steve Ross passed away late that year.

Annual revenues of the Warner Music Group, including all their labels, had reached $900 million in 1985. In 1993, that figure was $3.3 billion; profits reached almost $300 million. It was a bigger moneymaker than the movie business and the second largest contributor to Time Warner’s bottom line after the cable TV business. Ahmet (now seventy years old) and his colleagues just kept finding more talent and producing more hits. The company’s share of the American music market reached 22.2 percent, well ahead of perennial industry giant Sony/Columbia’s 15.3 percent.

With Steve Ross gone and Time’s Gerald Levin now leading the parent company, the executive offices became a revolving door. Ahmet had a string of new bosses. Some liked him, some did not, but Ahmet and his beloved Atlantic survived. When the axe fell on the executives working for him, Ahmet often did little to defend them. But they all learned from him and understood that Ahmet had no real loyalty to anyone or anything, except to Atlantic Records. They understood that he was in fact the master of the game, whether romancing the Stones or navigating the corporate boardroom. Ahmet Ertegun was above all else a survivor.

Some of the young hotheads brought into the Warner music empire at first thought, “What do I need this old guy around for?” But they soon realized how much he could teach them. One key young boss ended up having lunch with Ahmet twice a week, where he learned “everything he needed to know.”

Track Nine: Swinging Until the End

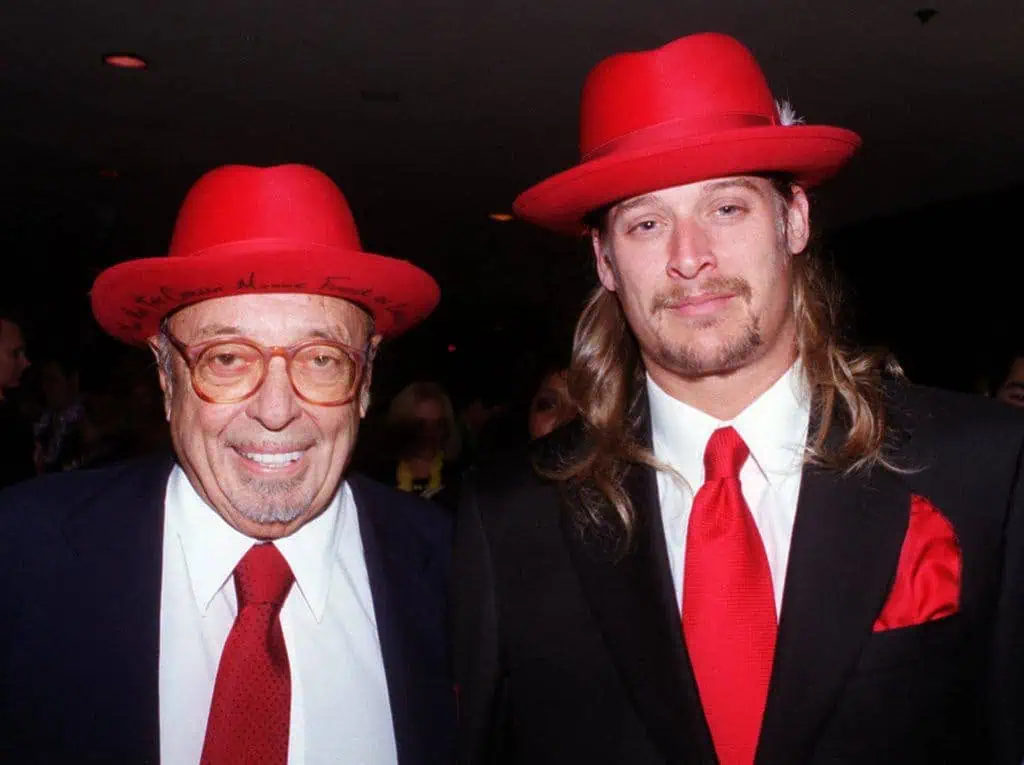

In 1998, seventy-five-year-old Ahmet “fell in love with” Kid Rock, hanging out with the youngster and becoming best of friends. Kid Rock had noticed that, during one of his Los Angeles performances, everyone in the audience was talking except this one old man with a cane, who listened intently: Ahmet Ertegun. Ahmet and Kid Rock even dressed alike, and Ahmet helped the young man through hard times.

Atlantic also produced Hootie and the Blowfish, Jewel, the Trans-Siberian Orchestra, and many other artists in this era. At seventy-seven, Ahmet could still occasionally be found at the mixing board, including working with Aretha Franklin in a tiny Detroit jazz club.

In 2000, Ahmet suffered a stroke and lost the vision in his right eye, but he never let it slow him down. The next year, he had triple-bypass heart surgery performed by fellow Turk Dr. Mehmet Oz. Nevertheless, he continued running around town well past midnight night with his young protégés and the rich and famous.

Into his eighties, Ahmet continued working with artists, sometimes in the studio. He also could listen to any record from the past, closing his eyes and “going into a trance,” then tell you all about it. He was one of the great storytellers, the ultimate raconteur. (Note that almost every classic anecdote from the music industry, including those we have recounted here, has not just two sides, but often three, four, or more. Everyone involved takes credit for each discovered artist with a hit; few take credit for the bombs.)

Ahmet’s last major record executive protégé was Craig Kallman, still today the chief executive of the Atlantic label within the Warner Music Group, now an independent public company generating over $4 billion in annual sales, even in the age of Spotify and Apple Music. (In 2008, Atlantic became the first label to sell over half of its recordings as digital files.) Kallman loves music as much as Ahmet did, amassing an incredible collection of over 750,000 records.

In 2006, Ahmet and Mica were scheduled to fly to Michigan for Kid Rock’s wedding to actress Pamela Anderson, but weather problems cancelled their flight plans. At the last minute, they instead decided to attend the Rolling Stones concert in New York. Backstage, Ahmet fell and hit his head. Six weeks later, on December 14, 2006, Ahmet Ertegun died at the age of eighty-three.

His heavy casket was flown to Istanbul in Microsoft billionaire Paul Allen’s Boeing 757, where Ahmet was buried next to his parents in an Islamic ceremony.

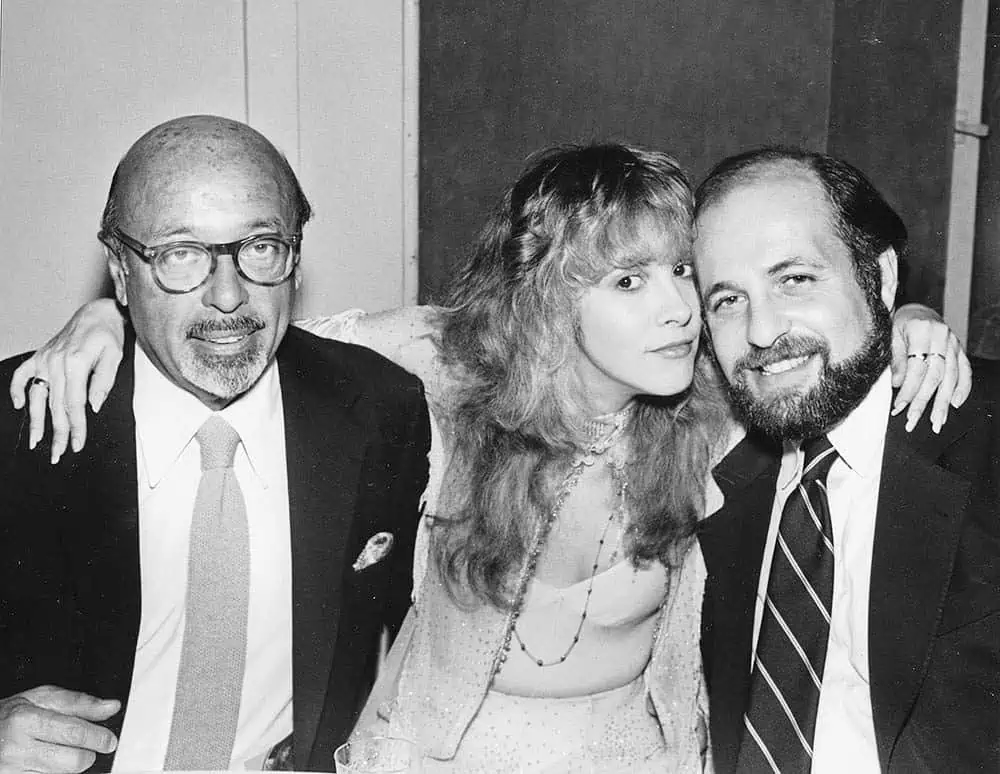

The following April, an invitation-only tribute concert was held in memoriam. Wynton Marsalis; Eric Clapton; Dr. John; Henry Kissinger; Michael Bloomberg; Bette Midler; Kid Rock; Sam Moore of Sam and Dave; Phil Collins; Stevie Nicks; Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone magazine; Mick Jagger; and Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young all spoke or performed, and cried, for the packed house. Later in 2007, Led Zeppelin headlined a tribute concert to Ahmet in London’s O2 Arena. Ahmet Ertegun would have been pleased.

(Mica, ninety-four years old as of this writing, gave a big chunk of Ahmet’s fortune to Oxford University for scholarships in the humanities and other funds to St. John’s College.)

Replay

Reviewing the preceding paragraphs, Ahmet Ertegun stands apart from the other great entrepreneurs and businesspeople we have covered in this American Originals series. The contrast could not be starker when compared with fellow entertainment visionary Walt Disney. Walt was a simple, down-to-earth Midwesterner, a son of the American soil. Disney was a loyal husband and family man. He was a straight shooter. He hated parties and did nothing to excess. He never sold out to the corporate world. Ahmet Ertegun was none of those things. He was, in fact, the polar opposite of Disney in almost every way.

Yet in studying the lives of these men and the other men and women in this series of biographies, we can see the enormous range of personalities and lifestyles lived by great innovators and pioneers. Only in the American system of free enterprise could such varied individuals survive and prosper, each in their own style. Adapting to technological changes, cultural changes, and financial challenges, each had a clear purpose, a vision. And that purpose was to be the best at what they did. Ahmet Ertegun may never be surpassed as a driving force in American popular music, which in turn covered the earth.

Source: this story is based on the book The Last Sultan: The Life and Times of Ahmet Ertegun, by Robert Greenfield (2011). Many books can be found on Atlantic records, recording studios, and the competing labels. When he was eighty-one, Ahmet did a rare TV interview with Charlie Rose (episode 10 here). Also excellent is a PBS special on Ahmet’s life and work.

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.