It was 1912. The wiry, soft-spoken, short (five-foot five-inch) immigrant with the thick Hungarian accent waited for hours to see the powerful Jeremiah Kennedy, head of the “Edison Trust” (Motion Picture Patents Company). Adolph Zukor, like many American Originals, had come to this country 23 years earlier with nothing. Now he had a vision that was to change America, the world, and the way all of us see that world.

Nickelodeons and early motion picture theaters continually ran 5–10 minute reels showing chase scenes and pratfalls. But Zukor had the idea that audiences might enjoy something longer, a full “feature” story. He had invested his savings in the American rights to a 40-minute European film, Queen Elizabeth, starring the most famous actress of the day, Sarah Bernhardt.

However, no film could be shown on Edison projectors without a license from the Edison Trust, and films made by anyone but the 10 designated producers were suspect. These members of the trust were making plenty of money without rocking the boat or trying anything new. Jeremiah Kennedy had all the power. So Zukor waited. He told the story to Harvard students 15 years later:

After waiting long enough for the letter to be delivered, I called at the offices of the “trust” and applied to the receptionist to see Mr. Kennedy. One historian has written that I cooled my heels for seven hours in the anteroom. But that report is exaggerated. The wait was hardly longer than three hours. The discourtesy was not intentional, for I was not considered of enough importance to justify discourtesy. Patience always seemed to me more than a copy-book virtue, and I decided that here was a good time to be virtuous. When at last I was remembered and given a hearing, Kennedy was polite but cold. He sat behind his big desk, looking every inch the captain of industry, listening with some impatience while I recited my arguments. “No,” he said, “the time is not ripe for feature pictures, if ever it will be.” In the eyes of the trust, I was an outlaw.

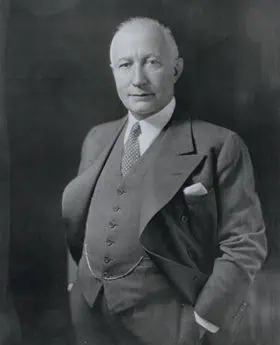

The “little man,” Adolph Zukor, would sooner or later get his way, and change the world as only a few other men and women have. Zukor’s story, and that of the empire he built — Paramount Pictures — is one of the great epics of innovation and entrepreneurship in American history. Let’s rewind to the beginning of this saga.

“In the eyes of The [Edison] Trust, I was an outlaw.”

Laying the Foundation

Adolph Zukor was born in the village of Ricse, Hungary, on January 7, 1873. A year later, his father died. His mother, who never fully recovered from the death of her husband, despite remarrying, died seven years after that. As his stepfather had no use for Adolph, he was sent off to live with his uncle, Kalman Lieberman.

Lieberman was a “stern, dedicated, argumentative Judaic scholar,” but Zukor wasn’t interested in arcane disquisitions on the Talmud and Jewish law. “What I was interested in,” he said later, “was the Bible … the story and the individuals — their lives fascinated me.” While his elder brother was a “success,” going on to become a rabbi in Berlin, there seemed little hope for Adolph, at least in his uncle’s eyes.

So off to a neighboring village went Adolph, where he apprenticed in a large dry goods store. The owners, the Blau family, took him in as one of their own. The Blau daughters introduced the boy to American pulp fiction — and his first view of American culture. He also devoured the Hungarian novelists and the great Western European writers like Dumas and DeFoe. Combined with his strong Jewish traditions of learning and storytelling, Zukor’s love of reading remained a lifelong passion.

Still, the young orphan was not satisfied. He could not imagine himself spending his life in the store, despite a generous offer to become a full assistant for $2 a month salary. Zukor later said, “I had no father and no mother, and I had nobody that lay awake at night to figure out how to educate me … I was alone.”

With great effort, he convinced his uncle and the orphans’ authorities to let him have $40 and passage to America, the land of dreams. In 1889, at the age of 16, he sailed for the US in the lowest class of passage. He sewed the $40 into the lining of his clothes to ward against theft, and slept in those clothes in his bunk during the long, unpleasant passage.

Upon arrival, as an Eastern European Jew, he was looked down upon, not only by the sometimes-wealthy German Jews who had arrived years earlier and “made it,” but by everyone else as well. This did not stop him. He got a job working as a furrier’s apprentice at $2 a week. He went to night school to learn English by 1891, though he never lost his thick accent. He “assimilated” as fast as he could. He took up boxing, earning a cauliflower ear, and later became a baseball enthusiast and player. He exercised throughout his life.

He also became an excellent fur designer, striking out on his own as a contract worker at 19, selling his own furs. Zukor clearly had the entrepreneurial bug, the desire to be the master of his own fate.

In 1893, the talk of America was the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. This great world’s fair attracted a bigger share of the American people than any fair before or after. Dreamers and innovators including Henry Ford and Henry Heinz were there. So was 20-year-old Adolph Zukor.

Impressed by the booming city, he stayed and became a 50% partner (and main designer) in the Novelty Fur Company, specializing in fox clasps. The first season, the partners each cleared $1,000. The next season they expanded to 25 men. They each cleared $8,000 (in today’s money, $234,000).

In 1896, the partners split, Zukor taking the Chicago operation and his partner taking the branch in Peoria. Zukor sunk all his money into a voguish fur cape, but this time his instinct failed him. The cape was a disaster. Adolph was learning the vagaries of a fashion business, one subject to fads and fizzles. In 1897, he had seen his first motion picture, lasting less than a minute, and found it fascinating.

But he was broke again. Bailed out by another furrier, Morris Kohn, in 1896, the two went into a partnership which lasted 10 years. And Zukor married Kohn’s niece, the beautiful and lively Lottie Kaufman, in 1897. In 1899, they opened a New York office. The partners moved to New York in 1900.

There he met fellow furrier Marcus Loew, three years older. Loew was born on the Lower East Side of Manhattan to a poor family, but prospered in furs and then invested in real estate, especially Vaudeville theaters. Loew suggested Adolph rent an apartment across the street from his own home, and they became lifelong friends. Years later, Zukor’s daughter Mildred married one of Loew’s twin sons. Neal Gabler, in his fascinating book An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood, says,

Though they were friends, after a fashion, two men could not have had more dissimilar temperaments. Zukor was quiet, grave, measured, and private. Loew was garrulous, chipper, impulsive, and extroverted. Zukor had extraordinary foresight but moved with extreme caution and deliberation. Loew had less foresight but was far more apt to take chances.

In 1902, Zukor guessed that red fox was going to be the fashionable fur of the season, and this time his prophecy proved correct. In 1902 and 1903, the company rode the wave of the fad in red fox. The company’s profits soared. Zukor, barely 30 years old, estimated his own windfall at somewhere between $100,000 and $200,000 ($2.8 to $5.6 million today). Zukor was learning how to dominate a market. And he had the cash to pursue his passions and consume his abundant energies.

“One historian has written that I cooled my heels for seven hours in the anteroom. But that report is exaggerated. The wait was hardly longer than three hours. The discourtesy was not intentional, for I was not considered of enough importance to justify discourtesy.”

Famous Players in Famous Plays

An opportunity came in 1903 when a fellow named Mitchell Mark needed the money to open a penny entertainment arcade, money which Adolph, his fur partner Morris Kohn, and others put up. Phonographs (with multiple recordings to choose from) were the most popular, but there were also peep shows, punching bags, and target practice games – all a penny each. Named “Automatic Vaudeville” (as opposed to live Vaudeville) it was located on 14th Street near Broadway, facing Union Square. Automatic Vaudeville took in $100,000 in pennies the first year. While it was a side venture to the fur business, Zukor said, “I couldn’t keep away from the arcade.” Before the end of 1903, they had expanded to Newark, Philadelphia, and Boston. Soon enough he dropped out of the fur business.

Zukor started showing motion pictures on the top floor of Automatic Vaudeville. The theater had 200 seats and offered a 15-minute show for a nickel. Zukor said, “Most of our customers didn’t know what moving pictures were and were used to paying one cent, not five. So we put in a wonderful glass staircase. Under the glass was a metal trough of running water, like a waterfall, with red, green, and blue lights shining through. We called it Crystal Hall, and people paid their five cents mainly on account of the staircase, not the movies. It was a big success.”

In his autobiography Zukor says, “In the Crystal Hall it was my custom to take a seat about six rows from the front. … I spent a good deal of time watching the faces of the audience, even turning around to do so. … A movie audience is very sensitive. With a little experience I could see, hear, and “feel” the reaction to each melodrama and comedy. Boredom was registered — even without comments or groans — as clearly as laughter demonstrated pleasure.”

In 1906, Zukor and theatrical entrepreneur William Brady bought the New York rights to Hale’s Tours, which had been a big hit at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. This concept consisted of a Pullman railroad car, or likeness of one, rigged up inside a theater. Ticket collectors were dressed up like railroad conductors. Customers took their seats, bells clanged, the whistle tooted, and the car would rock and shake. The filmed travelogues of distant places would then be projected onto a screen at the end of the car. The first one, in New York, was a big hit.

Zukor took the idea to Pittsburgh, Newark, and Coney Island. But the novelty soon wore off once customers had seen the show. Zukor begged the film producers — all those in the Edison Trust — to make more travelogues like the ones he had of Switzerland and Italy, but they couldn’t be bothered with the expense. Soon the business collapsed and the company was $160,000 in debt. Again, per Neal Gabler’s book:

His partner, the well-known Vaudeville entrepreneur and producer William Brady, suggested they declare bankruptcy. “It was as though I had touched him with a live wire. … I never dreamed he had such a temper. … ‘I won’t go into bankruptcy! I won’t!’” For Zukor, who had the sternest and least forgiving of moral codes, bankruptcy was not so much an admission of defeat as the breaking of an obligation. To break an obligation was tantamount to lying — one of Zukor’s cardinal sins.”

Instead Zukor converted the Hale’s Tour locations to movie theaters, not unlike the Crystal Hall. At the end of two years he had retired the debt and was showing a profit.

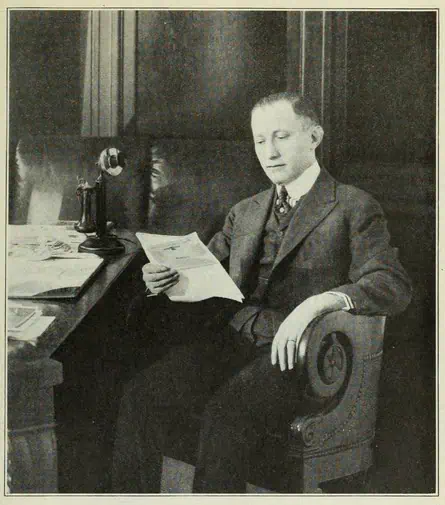

Throughout these years, Zukor was continually frustrated by the lack of good content to show in his theaters. With his love of great novels, plays, and stories, he believed the public was ready to stay longer and enjoy a “feature” motion picture. But he had no intention of producing pictures himself, saying, “I had no experience in making pictures and nothing was farther from my mind.”

By 1909, it was suggested that Zukor and his associates combine their theaters with Marcus Loew’s now larger chain. They pooled their assets into Loew Enterprises, and Zukor retired from active management. He later told the Harvard students:

Turning my interests into Loew Enterprises gave me an opportunity to be foot-loose. I was well-taken care of: the corporation paid good dividends, and from 1909 to 1912 I made a study of moving pictures. I traveled all through Europe and this country, watched the audiences, and was interested in any picture that had a subject that I felt would appeal to the public. In my own mind I wanted to verify whether my judgment was right. I would go to a theatre, take the first row or sit in a box and there study the audience and see what effect the picture had on them … In 1911 I made up my mind definitely to take big plays and celebrities of the stage and put them on the screen.

He came to believe that the motion picture industry would only prosper if he raised the stature of the films he showed. Zukor said, “It occurred to me that if we could take a novel or a play and put it on the screen, the people would be interested. We should get not only the casual passers-by but people leaving their homes, going out in search of amusement.” “Famous Players in Famous Plays” became his watchword. Zukor moved into film production. To learn, he observed pioneering filmmakers Edwin S. Porter and D. W. Griffith at work. The man’s curiosity was boundless.

Zukor later said, “Everybody thought I was crazy and told my wife I’ll lose all my money — made all kinds of predictions why I’ll ‘go to the wall.’ Nobody believed that people would sit through a picture for hours as they would a play. There were all sorts of reasons why the thing would not succeed.”

In 1911, he bought the US rights to the European film Queen Elizabeth, starring Sarah Bernhardt, the most famous actress in the world. He paid the outrageous price of $35,000. The film ran an incredible 40 minutes, twice as long as any prior film. In May of 1912 Zukor formed the Famous Players Film Company to release the movie. The premiere in July of 1912 was a major success. Zukor linked up with Broadway producer Daniel Frohman, one of the few theater barons who thought moving pictures might have a future. Zukor and Frohman convinced Broadway star James K. Hackett to do a film version of his hit play The Prisoner of Zenda. Zukor sold his position in Loew’s and funneled all his money into Famous Players. By the summer of 1913, the company had produced five feature films and decided to enter the European market, among the first Americans to do so. (Foreign revenues today represent half or more of most movies’ box office receipts.)

“He had a vision that was to change America, the world, and the way all of us see that world.”

Throughout this period, the Edison Trust fought him, as evidenced by his meeting with Jeremiah Kennedy described earlier. But the box office results of Zukor’s films proved him right — and people were even willing to pay a dime rather than a nickel (at a time when Broadway’s live theater charged $1.50). Gradually other filmmakers followed Zukor’s lead. The Edison Trust cracked when the Eastman Kodak Company agreed to sell their critically important film stock to the independent producers, the “outlaws.” The Motion Picture Patents Company was soon powerless and forgotten.

One of his biggest challenges was finding actors who could make the transition from stage to film. Few knew how to perform for a camera. One young stage star, Mary Pickford, had done some film work, and Zukor offered her $500 a week compared to the $175 she was making on Broadway. By 1916, she was being paid $10,000 a week, the equivalent of $220,000 today.

Zukor in 1916 merged his Famous Players Company with friend Jesse Lasky’s independent firm, which had already completed 21 features based on plays and novels by 1914, creating Famous Players-Lasky.

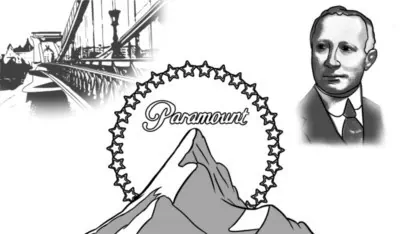

At the same time that Zukor was building his production company, William Hodkinson had created Paramount Pictures in 1914. Paramount was neither a theater operator (“exhibitor” in the language of the industry) nor a producer of films, but a distribution company. Distribution is the great unseen force in the movie industry, the link between producers and exhibitors, the conduit through which the “product” flowed. Hodkinson wanted to create a national distribution system, compared to the regional and state operators that were the standard. He went further, providing capital to producers prior to production, in effect financing the industry. Then he took the films and determined which theaters to best show them in, set the rental prices, handled the advertising, and split the proceeds 35% to Paramount and 65% to the producer. The company was owned by all the participating producers. Hodkinson also created one of America’s great corporate logos, the Paramount Mountain ringed by stars.

Famous Players and Lasky were founding members of Paramount, as the idea of uniform national distribution appealed to Zukor. When they merged, they became key to Paramount, providing three-quarters of their films. Zukor bought out the other producers and in 1916 replaced Hodkinson as president — with himself.

While Famous Players-Lasky and Paramount boomed, the times were not without challenges. World War I cut off the European market, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 closed theaters nationwide for most of two key months. The combined Paramount-Famous Players production and distribution enterprise lost $1.25 million, its first annual loss. Despite the war, by 1920 Zukor’s Paramount had distribution around the globe — from Europe to Asia, from Australia to South America — everywhere but the USSR.

Another challenge was the rise of First National Exhibitors’ Circuit (later First National Pictures), founded in 1917 by the merger of 26 of the biggest first-run theater chains in the United States. These theater owners combined out of the fear of the rising power of Paramount — and the possibility they wouldn’t be able to get the films they needed. Over time, they controlled over 600 theaters, and determined to go into film production, starting in 1917. Adolph Zukor tried to convince them this was not a good idea, that he could supply their needs, but to no avail.

In defense, Zukor, who had abandoned theater operation to concentrate on making movies, felt forced to get back into the theater business himself. In 1919, Paramount raised $10 million from Wall Street to keep up with Adolph’s ambitions. By 1921, Paramount had acquired 303 first-run theaters in major cities across America. It was the largest film-making and distribution company in the world.

Likewise, in a defensive move, his old friend and important New York theater-owner Marcus Loew had decided to get into production, buying the Metro studio in 1920. Assembling talent, Loew’s studio division was soon named Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), and became Paramount’s most powerful rival. But the industry was still embryonic, churning out only silent films.

“Everybody thought I was crazy and told my wife I’ll lose all my money. … There were all sorts of reasons why the thing would not succeed.”

The Paramount Empire in the Roaring Twenties

In 1923, Paramount released The Covered Wagon, which cost $336,000 to make but made a profit of $1.6 million. Those records were broken that same year with Cecil B. DeMille’s epic The Ten Commandments, the most expensive movie ever made up to that time at $2 million ($29 million today), using 2,500 actors, 3,000 animals, and 55,000 feet of lumber for set construction. It too made huge profits.

In July of 1925, Zukor announced a major expansion in his theater program, budgeting $20 million to build 22 new theaters. He also went on a buying spree, acquiring hundreds of theaters. But he needed someone talented to run those theaters, and toward that end, in 1926 he acquired control of the real gem: Chicago’s Balaban and Katz (B&K) chain, the most profitable group of movie theaters in the world.

B&K had been founded by Barney Balaban and four of his six brothers and their brother-in-law, Sam Katz. The Balabans’ mother, Goldie, who operated a small store, had noticed that customers paid their nickel at the nickelodeon without even knowing what they’d see. She told her sons, “This is the business we need to be in!” Their fifth theater, the Central Park on the west side of Chicago, was the first true “Picture Palace.” This was the first air-conditioned theater — with fans blowing air over blocks of ice. It was therefore the first theater open throughout the formerly intolerable summer.

But B&K, under Sam Katz’s leadership, went further than that — triumphal arches, grand staircases, uniformed ushers, pipe organs, orchestras, child care centers with sandboxes and slides — things never before seen in a movie theater. With financing from Sears’ Julius Rosenwald, Yellow Cab founder and car rental pioneer John Hertz, and chewing gum magnate William Wrigley, B&K developed a chain of over 40 theaters in the Chicago area, with their supreme achievement being the Chicago Theater on State Street, still in operation today. Zukor put Sam Katz in charge of his entire theater empire, now renamed Paramount-Publix. Barney Balaban stayed behind and ran the important Chicago operation.

The 1920s also showed Zukor’s odd combination of foresight and caution. On the one hand, Paramount made a small investment in William Paley’s struggling but promising radio network, CBS, buying a half-interest. Zukor always had more respect for broadcasting than his movie-making peers. On the other hand, at first Zukor rejected the “talkies” when they arrived in 1927, led by the Warner Brothers and Fox studios. An expensive and unproven technology, film-makers were concerned that they would lose their large immigrant audiences who did not speak English. But soon enough, Zukor came around, and all Paramount theaters had sound systems installed.

With Katz’s skills and Paramount’s money, the company controlled 1,600 theaters by the end of the 1920s, more than all the other movie companies combined. As of late 1929, it had paid dividends for 44 consecutive quarters, totaling $32 million since Zukor started it. Corporate profits rose from $5 million a year in the mid-twenties to $8 million in 1927. Revenues of the theaters rose from $30 million in 1927 to $113 million in 1930. The studio (production part of the company) had record revenues of $69 million in 1930.

Paramount was at the top of its game. Adolph Zukor’s whole net worth was tied up in his $50 million worth of Paramount stock in 1930, as the stock reached as high as $78 per share. His 1929 salary and bonus was $900,000, equivalent to $13.2 million today.

In 1926, Zukor broke ground on the Paramount building at 42nd and Broadway in New York, right on Times Square. This skyscraper would include their $5 million Paramount Theater, showcase of the corporation.

Marcus Loew felt that perhaps Zukor’s ambition had been too great, his moves too fast. He watched the construction of the new building from his office across the street. Gabler says,

Loew, ever cautious and conservative, regarded Zukor’s ambitious moves with anxiety and misgiving. He would stand at the window and gaze down into the hole they were excavating for the new Paramount building and theatre, and shake his head sadly and mutter, “Adolph is digging his grave.”

The multiple ironies in this statement only became clear in coming years. Marcus Loew died of a heart attack on September 5, 1927. He was 57 years old.

But perhaps the most interesting paragraph comes from the biography of Zukor, The House That Shadows Built, written by Will Irwin and published in 1928. The last chapter ends with this paragraph:

As I write, Adolph Zukor is fifty-four years old; and the work is done that he was born to do. Looking out from his tower on late winter afternoons, he beholds a field of glittering electric signs which proclaim the triumph of his idea. They mark the moving-picture houses which, stably and exclusively, hold Times Square. As though in revenge for the days when Broadway snubbed the hoydenish cousin of Union Square, they have pushed the spoken theatre into the side streets. His creation stands rounded and complete. What with his native constitution, his moderation in eating and drinking and his systematic exercise, he may have twenty years of work still in him. But the rest will be an easy pull up a gentle slope. Struggle is over for him — and perhaps his creation.

Such was not to be the case, for Adolph Zukor’s (and Paramount’s) struggles were far from over.

Depression and Collapse

At first, in 1929 and 1930, the Great Depression did not have much impact on the movie industry. But that would soon change as the nation dug deeper into the economic ditch. In 1929, Americans spent $720 million on movie tickets; four years later that had dropped by one-third, to $482 million. From a high of $113 million in 1930, Paramount’s theater revenues dropped to just $25 million. In 1932, the company lost an astonishing $21 million on the bottom line.

Making matters worse, the huge theater acquisition program carried with it debts of millions in mortgages and bonds. In some cases, Zukor had paid in stock, but promised to buy back the theater sellers’ shares at $80 a share — obligations totaling over $11 million by the early 1930s, one of his most significant mistakes. But the stock collapsed from $78 to $8 a share. There was no way out but bankruptcy and receivership. Zukor was out. Katz was out. “Fifty-three different law firms, banks, protective committees, and experts yammered and bled for two and one-half years over the sick giant and its 500 subsidiaries,” according to Fortune magazine. In a few years, 10 changes were made to the board of directors. Financial types, not movie people, went through the revolving “leadership” door. Had Adolph Zukor’s dreams come to an end?

Recovery

When in 1935 the dust settled and a plan of reorganization was approved, Barney Balaban of Chicago theater fame emerged as president of Paramount, with Zukor’s blessing. Not only did the “old man” end up on his feet, he was named chairman of the board, and moved from New York to Los Angeles to oversee the now-troubled studio.

Barney Balaban understood the business inside out. Trained as an accountant, he was “a devil with figures.” He watched 250 movies a year, international and domestic, those of Paramount and all their competitors. Every Monday morning he reviewed the week’s box office take. He sold a half-interest back to many of the regional theater chain owners they had bought out, or contracted with them to operate the theaters on Paramount’s behalf. The company sold Bill Paley back their half-interest in CBS at a bargain price. Whatever it took to raise cash.

All these steps worked. In 1936, the company made a profit of $6 million. By 1945, the number was $17.9 million. In 1946, Paramount made $44 million, the most money of any movie company in history, twice the nearest competitor. The company was by then free of debt and had $31 million in cash in the bank. And it still owned all or part of 1,537 theaters, by far the largest chain. With Zukor’s enthusiasm, the company even made an investment in television, which most of the other movie moguls hated. They owned 29% of the Dumont Network, and owned stations in Chicago and Los Angeles.

Zukor’s initial insight that people would sit still for a great story was more than vindicated in 1939 when the almost-four-hour-long Gone With The Wind (from MGM) broke all box office records. As of 2017, it is still the largest grossing movie of all time if one adjusts for inflation in ticket prices.

Still, the waters were not permanently calmed. Television did rise quickly. In 1946, Americans bought a grand total of 6,500 television sets. By 1949 there were 4 million television homes; by 1959, 41 million. While some studios fought TV — banning their movie stars from appearing on it — Paramount became involved in producing television series. That didn’t help the theaters, which were cash-rich but declining in revenue.

In 1948, after years of trying, the federal government was able to break up the movie giants, forcing them to separate their theater chains from their studios. In 1950, Paramount spun out United Paramount Theaters to its shareholders. It was the largest theater chain in the nation, now run by Barney Balaban’s young protégé, Leonard Goldenson.

Looking for ways to grow his new company and use his ample cash reserves, Goldenson in 1951 purchased the American Broadcasting Company (ABC), a distant third in the television race against giants NBC and CBS. Goldenson hoped to use movies to boost his network’s position.

In his book Beating the Odds, Goldenson tells of the reaction of media barons to his plan to acquire ABC. He got three calls, the first from Nick Schenck, head of Loew’s and MGM, successor to Marcus Loew. Schenck said, “You’re a traitor. … You’ll be competing with movie theaters for the audience’s time.” The second call came from “General” David Sarnoff, the potentate of RCA and its NBC subsidiary. Sarnoff said, “Who’s going to watch film? Audiences want to watch things live.” Sarnoff suggested he rerun old programs from NBC and CBS. The third call came from Adolph Zukor, approaching 80 years of age. Zukor said, “You now have a great opportunity to reach many more people than we could ever reach with motion pictures. I want to tell you how much I admire what you’re doing in trying to establish a viable third network.” Goldenson added, “Zukor’s blessing banished all the doubts I’d harbored since I first went after ABC.”

After Barney Balaban retired in the mid-1960s, Paramount fell into the hands of conglomerate mogul Charles Bluhdorn’s Gulf & Western Company. Today it is part of Sumner Redstone’s Viacom. The studio may have seen its best days: over the five years since 2011, Paramount has ranked sixth or seventh among the big movie studios in box office revenue. The list has often been led by Disney in recent years, in part due to its acquisitions of Lucasfilm (Star Wars) and Pixar (from Steve Jobs). Perhaps Paramount might have made these foresighted acquisitions had Zukor remained in the driver’s seat.

“My father would discuss all the events of the day, good and bad. And if disaster was ahead we would know it and be prepared for it. And if he had made a mistake in judgment, we would know it.”

— Eugene Zukor

Outlasting them All

It has been said that Zukor predicted he would “outlive all his enemies,” though with his partnerships and friendships with almost everyone in the industry, competitors might be a more fitting word than enemies. But Adolph’s prediction turned out to be right. He outlived virtually everyone of his generation.

At the age of 80, he wrote his autobiography, The Public is Never Wrong. His closing line of the book was “The film industry is still in swaddling clothes. The great days lie in the future.” His optimism never abated.

At 83, in 1956, he lost his beloved wife of 59 years, Lottie. His son, Eugene, reminisced, courtesy of interviews with author Gabler:

No matter how dire their financial circumstances, he never failed to give her two dozen long-stemmed roses for her birthday and a letter expressing his love for her. … For her big event, the Ladies’ Aid Society Ball, he got Clark Gable or Maurice Chevalier to show up.

And Lottie always stood by him, through thick and thin. Says Eugene: “She would say, ‘Well, so we move again. I’ll find a place. Now how much can we afford?’ So Pa said, ‘As little as possible and still be near a good school.’”

His belief in education and learning was another constant throughout his life.

Amazingly, Adolph Zukor continued as chairman of the board of Paramount until 1964, when he was “kicked upstairs” to chairman emeritus, at the age of 91. His younger colleagues were smart enough to keep the old boy around for counsel.

His son, Eugene, continues:

At ninety-three he still smoked three cigars a day, though he had been forced to surrender his daily steambath. At ninety-six he was living alone in an apartment at the Beverly Hills Hotel. At ninety-seven he was still spending two hours at the studio each day, scanning the Paramount grosses every Monday morning just as he always had. At one hundred he had moved to a high rise in Century City and hired a young housekeeper, but he shuffled out for daily lunches at the Hillcrest Country Club and then watched the afternoon bridge games.

In January of 1973, Paramount threw a huge celebration of his 100th birthday. Over a thousand people crowded the ballroom in a Los Angeles hotel.

On June 10, 1976, Adolph Zukor, dressed in suit and tie as he always was, took a nap and never woke up. He was 103 years old.

Zukor’s lifelong commitment to exercise could not have hurt — he was known to take night walks, and at least once walked halfway down Manhattan and back, from Central Park to the Battery.

He apparently passed his genes or his will to live to his son, Eugene, who lived to 97. Eugene’s wife had died a year earlier, after 73 years of marriage. Both men were the ultimate family men, in an industry not known for marital fidelity. More from Eugene:

I can hardly remember a time when the four of us — my father and mother and sister and I — didn’t sit down to dinner together. My father would discuss all the events of the day, good and bad. And if disaster was ahead we would know it and be prepared for it. And if he had made a mistake in judgment, we would know it. We were always moving from an apartment with an elevator and servants to an apartment over a candy store, from Riverside Drive to Broadway.

Insights and Lessons from the Life of Adolph Zukor

The man was not perfect. Instead, he was human. We have seen how his optimism hurt him when he promised to repurchase Paramount stock for $80. He was stung and dethroned by the Great Depression.

Like any person of achievement or power, he had plenty of detractors. When he passed into his 90s, Louis B. Mayer’s daughter Irene Mayer Selznick said, “There was barely anyone around to remember how rough and ruthless he could be.”

At the same time, in a business full of profligates, Zukor retained his strong if stern moral code. Some called him puritanical. And he had a temper, as shown in these stories provided by Neal Gabler:

Adolph Zukor hated two things. One was losing. It didn’t matter what the stakes were. A friendly bridge game with his associate Marcus Loew could suddenly erupt, as one witness noted, into a shouting match followed by the crash of a table. “Loew came out, followed by Zukor, who was trembling with rage. After some discussion, the host cleared up a point about a certain club lead,” but the antagonists still refused to speak to one another. On another occasion Jesse Lasky, a rival producer, tried to lure away one of Zukor’s stars. Zukor topped Lasky’s initial offer, and a bidding war ensued, with Zukor upping the ante by one or two thousand dollars each time, until Lasky finally folded. Then Zukor promptly turned around and lent Lasky the star for his next production. The victory was all.

The second thing Zukor hated was being lied to. Once, he invited a new member of his company’s sales staff to one of his famous bridge games. The man had claimed some expertise in cards, but after the first bid Zukor could see he had been bluffing to win favor. After the third deal, remembered Zukor’s son, Eugene, “My father took the deck of cards and threw them on the floor. He said, ‘I can tolerate a person who will admit he doesn’t know. … But you said you are a bridge player, and you don’t know the first goddamn thing about it, and you spoiled our whole evening and this I won’t tolerate. … As far as I am concerned, you can leave right now.” And the guy packed up and went home.’”

As he turned the ABC Network into a powerhouse, Leonard Goldenson sought the aging Zukor’s advice every time he went to Los Angeles. Perhaps his comments offer a more well-rounded perspective on the old man:

Under him, Paramount had been the first to induce stars from the legitimate theater to make movies, the first to make movies in Hollywood, first to produce feature-length films, first to distribute and exhibit color movies, first to import foreign talent for American movies, and the first to introduce American films abroad.

Zukor had a lot of courage. Even after he was wiped out, the old man never lost his bearings. Until he was ninety-seven, he went to the studio every day for a few hours. He had an almost innate sense of what people wanted to watch.

To me, Adolph Zukor was the greatest showman of his generation. His appreciations of programming, promotion, and advertising remained unfailing almost up to his death … his mind remained crystal clear. He wanted to know everything about each picture. Not only Paramount’s films but those of the other studios as well. He made the most astute observations as to why a picture didn’t do well. His counsel benefited the company almost to the day he died, at age 103, in 1976.

Even Gabler, who entitled his chapter on Zukor “The Killer,” had to admit:

Few rulers relished their role of leadership as much as Adolph Zukor relished his. He was the self-possessed, genteel master — cautious, remote, seigniorial, conscious of his position. The pose was respected. Zukor became the father confessor of his associates and friends; they would call him regularly on personal matters as well as business. Even competitors sought audiences to receive Zukor’s counsel. On one occasion Carl Laemmle, the head of [competitor] Universal, made a courtesy call, ostensibly to discuss the state of the industry, but he soon confessed that he was having some serious financial difficulties. Zukor offered to contact his banking connections and vouch for Laemmle, and he did.

Within the context of the study of entrepreneurship and innovation, Zukor stands tall. As is common in most of the great innovators, he was obsessed with listening to the customers and caring about the “average person,” not just the stars whose fame and fortunes he helped create. He was a lifelong learner and reader. He learned from his experiences — by combining an understanding of storytelling and of how fads come and go, he became the ideal leader of a movie studio. He was never afraid of failure, and confronted it calmly and realistically. He had partnerships and friendships that lasted his whole life. He was above all else a survivor, in every sense of the word.

Ironically, the movie industry rarely celebrates the lives of our great business leaders and entrepreneurs these days. Perhaps they think there is not enough drama there. It would be hard to think of a better theme for a biographical picture (“biopic”) than the saga of their own Adolph Zukor, the man who saw the movie industry in his head, long before the rest of the world had ever seen a feature film.

Notes on Sources and Further Reading: The motion picture industry is one of the best-documented businesses in the world, with thousands of books about the companies, their leaders, their directors, and their stars. My favorite concise history of all the major studios is The Hollywood Studio System: A History, by Douglas Gomery (2005). Well-written with original research but opinionated is An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood, by Neal Gabler (1988), the source of many quotes in this article, including those of Eugene Zukor. Zukor’s own words come from his autobiography, The Public is Never Wrong: My Fifty Years in Motion Pictures, by Adolph Zukor with Dale Kramer (1953), and from the outstanding but more expensive The Story of Films, a compilation of lectures given at Harvard by most of the industry leaders and edited by Joseph P. Kennedy, who organized the lectures (1927). Zukor’s biography, The House That Shadows Built, by Will Irwin (1928), contains a lot of great detail.

Gary Hoover has founded several businesses, each with the core value of education. He founded BOOKSTOP, the first chain of book superstores, which was purchased by Barnes & Noble and became the nucleus for their chain. He co-founded the company that became Hoover’s, Inc. – one of the world’s largest sources of information about companies, now owned by Dun & Bradstreet. Gary Hoover has in recent years focused on writing (multiple books, blogs) and teaching. He served as the first Entrepreneur-In-Residence at the University of Texas’ McCombs School of Business. He has been collecting information on business history since the age of 12, when he started subscribing to Fortune Magazine. An estimated 40% of his 57,000-book personal library is focused on business, industrial, and economic history and reference. Gary Hoover has given over 1000 speeches around the globe, many about business history, and all with historical references.