Introduction

Universal recognition is the most widely adopted occupational licensing reform in U.S. history. Since 2013, 21 states have adopted the policy, which allows an individual with an out-of-state license to obtain a new license through a low-cost relicensing procedure. Ohio, Virginia, and Arkansas are the most recent states to pass this reform in early 2023, and several other state are considering it now. Licensing imposes costs on both consumers and workers and research from the Archbridge Institute, titled Too Much License?, suggests growth in occupational licensing may limit opportunities for upward economic mobility. Up to this point, however, it has been unclear whether universal recognition effectively reduces licensing barriers to labor market entry and geographic mobility.

The rationale behind universal recognition is simple and powerful. State licensure limits the labor market participation and mobility of people who have an occupational license issued by one state and want to practice in another state.

For example, these people may include licensed practitioners who move across states to follow their spouse or those who want to find a new business opportunity in a neighboring state. Under the existing system, these individuals are often required to complete additional training or exams to obtain a new license, which discourages or delays their entry into the labor market of their new state. Universal recognition is expected to lower relicensing costs of movers across states, thereby improving their access to the labor market and boosting the local economy. Given that these workers are already licensed and qualified, there are no obvious costs to consumers and workers from this reform. Further, there is no documented evidence of consumers benefitting from differences in training requirements. Haircuts are not better in Iowa, where barbers are required to complete 2,100 hours, than in New York, where barbers are required to complete less than 300 hours of education and training.

We examined the labor market effect of universal recognition in a new working paper, Now You Can Take It with You: Effects of Occupational Credential Recognition on Labor Market Outcomes. The paper presents empirical evidence on the positive labor market effects of universal recognition.

- After the policy, we observed a near full percentage point increase in employment among individuals in affected occupations.

- The policy is expected to add at least 67,000 new jobs across U.S. states.

- We found evidence of a nearly 50 percent increase in migration into states with universal recognition among individuals with low portability licenses.

However, we also found some evidence that the policy effect is larger in some states than others. The heterogeneity seems to be related to variations in universal recognition laws across adopting states. For example, universal recognition tends to have had large labor market effects in states that do not require substantially equivalent licensing requirements between the state of universal recognition and that of original licensure. For the rest of this brief, we detail variations in universal recognition laws and link them to our research findings on mixed policy effects across states.

Variations in Universal Recognition Laws

As a standardized relicensing procedure, universal recognition commonly requires a state’s licensing authority to issue an occupational license to individuals who have a license issued by another jurisdiction and meet several requirements. However, universal recognition laws differ by states at least in three dimensions: additional requirements for universal recognition, the scope of eligible occupations, and specific provisions for compliance. Table 1 shows a list of universal recognition laws in 21 states that were passed since 2013.

First, states typically ask applicants to meet several requirements to be eligible for universal licensure recognition. For example, nine out of 21 states demand licensees meet a “substantially equivalent” licensing standard. This provision requires an applicant’s original license to be issued by a jurisdiction with more or equally stringent licensing requirements. In addition, six states require residency for universal recognition.

Next, states allow universal recognition for different sets of occupations. Many states write explicit provisions in the universal recognition law to exempt certain occupations. On top of that, there is a common loophole to exempt occupations regulated by a different chapter of state code than the one codifying the universal recognition law. These occupations typically include several large occupations such as teachers, lawyers, insurance agents, emergency medical technicians and paramedics, and pest control workers.

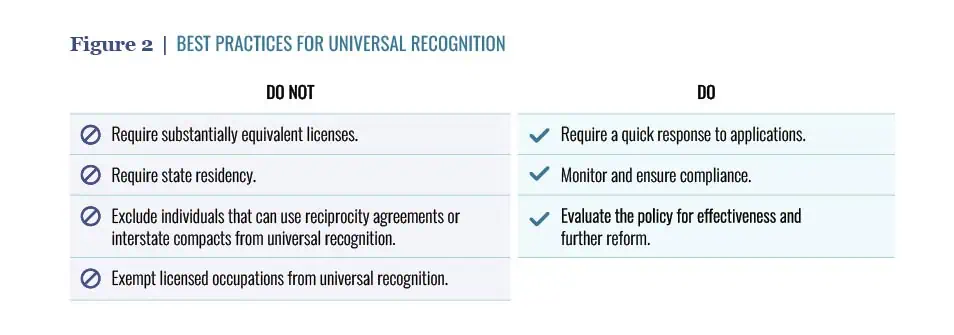

Third, several states have specific provisions to improve the compliance of the state licensing authority in accordance with universal recognition laws. For example, some states ask the state licensing authority to respond to an application for universal recognition within a certain number of days. In addition, several states require the state licensing authority to report detailed information on their responses to applications. Also, some states try to enhance the visibility of the policy by requiring information to be posted on the state licensing authority’s website.

Interestingly, states seem amenable to revisiting and improving past legislation to unlock the full potential of universal recognition. The requirement for a substantially equivalent licensing standard has been gradually fading over time. Missouri and New Mexico initially required it but removed the provision after Arizona passed a landmark bill without it in 2019. All three of the latest universal recognition states do not require a substantially equivalent license. Further, several states, including Nevada, Missouri, New Mexico, and Utah, expanded the scope of eligible occupations with major amendments, as shown in Table 1.

Labor Market Effects of Universal Recognition Across States

Universal recognition should reduce the costs of relicensure after a move. Economic theory suggests this policy change should encourage 1) more people to move into the state, and 2) more people to find work after a move. For an empirical analysis of the policy effects, we compare the labor market outcomes of individuals in licensed occupations, relative to unlicensed individuals, before and after the policy, using 18 states with the policy and other jurisdictions without it. Our sample is the working-age population (18-64) in the American Community Survey (ACS) 2005 to 2021.

Consistent with theory, we find that universal recognition improved both the labor market activity and geographic mobility of licensed individuals. After the policy, the employment ratio increased by 0.98 percentage points among the 860,752 licensed individuals in the sample, resulting from an increase in labor market participation and a decline in unemployment. Bringing more workers into the labor market is expected to spur economic activity and improve the livelihood of all citizens. Also, migration into states with universal recognition increased by 48.4 percent among individuals with relatively low portability licenses in the sample. Attracting new workers from other states may have a similar positive effect on the state’s economy.

We also found that universal recognition was more effective in some states than others, as shown in Figure 1. In our research paper, we explore the policy’s differential effect by several groups of states that adopted the policy in the same calendar year. First, the policy had the largest employment effect in Missouri, Iowa, Idaho, and Utah. Notably, none of them require a substantially equivalent licensing standard for universal recognition, and the first three states allow universal recognition for the broadest scope of occupations. Next, the policy resulted in a significant decline in the unemployment rate in Nevada. Nevada uniquely requires its state licensing authority to quickly respond to the initial application and make a final decision no later than 60 days (or in some cases, 45 days). This likely plays a role in reducing unemployment spells while an applicant waits for a new license.

Conversely, universal recognition has been the least effective in New Jersey. We suspect this is driven by the reform giving too much discretion to licensing boards, causing them to operate a more restrictive universal recognition program than other states. Also, the scope of occupations eligible for universal recognition is relatively narrow. For example, real estate brokers and electricians cannot obtain a new license by universal recognition in New Jersey, though both occupations are major beneficiaries of the policy in other states.

Best Practices for Universal Recognition

Our research demonstrates that universal recognition is an effective reform for reducing licensing barriers across states. Given that individuals with out-of-state licenses are already trained and screened by other states, allowing them to practice without a time-consuming relicensing procedure improves service provision without compromising service quality. From this perspective, universal recognition could be particularly beneficial for states that experience a shortage of service professionals like healthcare workers.

The study also suggests several best practices. For the maximum benefits, states should not require a substantially equivalent licensing standard and/or residency for universal recognition. As of April 2023, seven states—Missouri, Utah, Idaho, Vermont, New Mexico, Ohio, and Virginia—meet this ideal (Table 1). Next, states should offer minimal exemptions to the universal recognition law. Missouri, Iowa, Idaho, Mississippi, Kansas, and Oklahoma are examples of states allowing universal recognition for the broadest range of occupations. In the same vein, it is recommended to provide universal recognition to individuals regardless of reciprocity agreements or interstate compacts, which are often more restrictive. Moreover, states may want to consider specific provisions to improve the compliance of licensing boards to the policy. Nevada demonstrates a best practice by enforcing a quick response to applications and monitoring compliance periodically.

To go further, states can consider an alternative pathway to licensing based on practice experience instead of an out-of-state license. This alternative is particularly relevant for occupations that are licensed in the state of recognition but not in other states. Currently, seven states including Vermont, Mississippi, Kansas, Utah, Ohio, Virginia, and Arkansas open this alternative pathway. Vermont and Utah go further by allowing occupational credential recognition for foreign-trained professionals. This extended program may help support local economies with a shortage of native professionals, as well as assist with the labor market assimilation of immigrants and refugees.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our research provides evidence that universal recognition is improving local labor markets by expanding employment opportunities and making it easier for workers to move from state to state, expanding their opportunities to achieve upward economic mobility. We outline best practices for state policymakers considering licensing reform. Universal recognition is a policy tool with no obvious costs and substantial benefits. These best practices can help maximize the policy effects.