EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Nostalgia is a psychological resource that improves well-being and energizes forward-looking, explorative, creative, goal-focused, and prosocial activities. In this way, nostalgia—though involving reflection on the past—is ultimately a future-oriented experience. While research has primarily focused on people’s sentimental reflection on their own autobiographical experiences (personal nostalgia), individuals also experience nostalgia for eras predating their lifetimes (historical nostalgia). Consumer retro trends point toward this phenomenon, with many people gravitating toward products, aesthetics, and ideas from eras they never personally experienced. Yet there has been no systematic research on the prevalence of historical nostalgia and its perceived value in people’s lives.

To further advance our understanding of nostalgia as a psychological resource that extends beyond autobiographical memory, our team at the Human Flourishing Lab surveyed a nationally representative sample of just over 2,000 U.S. adults about how they experience and use historical nostalgia. We assessed Americans’ level of agreement with statements measuring their general feelings of nostalgia for eras before their lifetime, their attraction to products, media, styles, hobbies, or traditions from these periods, their beliefs about incorporating historical elements into contemporary design, and whether they find historical nostalgia helpful for managing present-day stressors and anxieties about the future.

KEY INSIGHTS

- Historical nostalgia is widespread, with most Americans reporting nostalgic feelings for eras before their lifetime (68%), attraction to products, media, styles, hobbies, or traditions from these periods (69%), and belief that contemporary design should incorporate historical elements (73%).

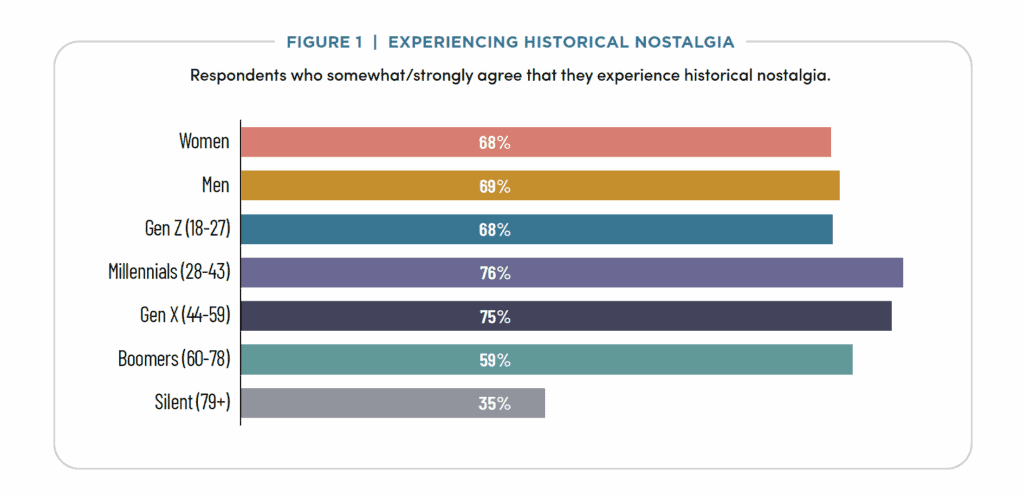

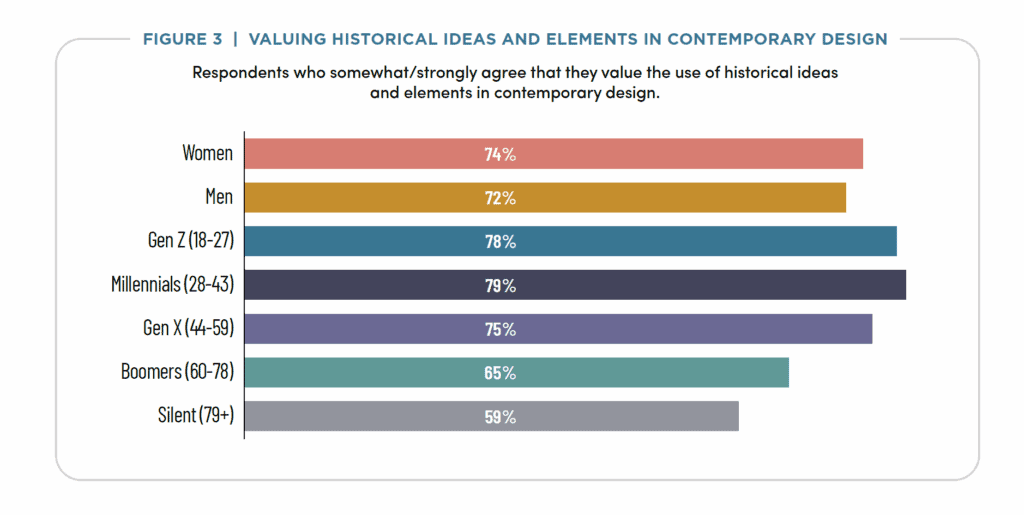

- Across indicators of historical nostalgia, a consistent generational pattern emerges: Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z show substantially stronger historical nostalgia compared to Boomers and the Silent Generation.

- Historical nostalgia appears to function as a psychological resource for many Americans, with a majority reporting they find it helpful both when feeling stressed or overwhelmed by modern life (63%) and when experiencing worry or anxiety about the future (62%).

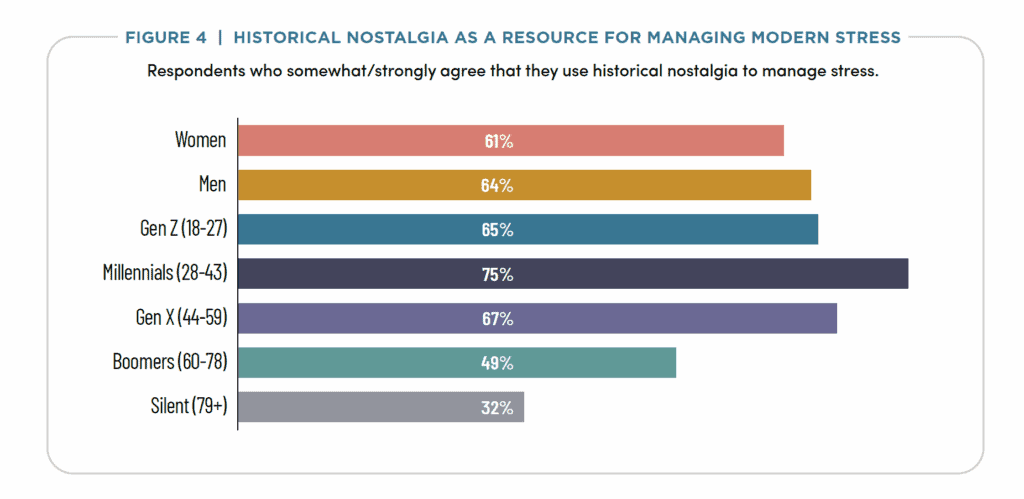

- The use of historical nostalgia as a psychological resource shows a clear generational divide, with Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z much more likely to utilize it compared to Boomers and the Silent Generation. Within this broader pattern, Millennials stand out as the most inclined to report using historical nostalgia as a psychological resource.

- Gender differences are minimal, with men and women reporting similar rates of historical nostalgia and its use as a psychological resource.

INTRODUCTION

The term nostalgia, first coined in 1688, originated as a medical diagnosis for what doctors considered a brain disease believed to primarily afflict Swiss mercenaries who were longing for their homeland. Even though nostalgia is now understood as a normal and universal human experience, many contemporary discussions often characterize it as an unhealthy fixation on an idealized past that prevents people from embracing the present and productively planning for the future. However, contemporary behavioral science research has revealed nostalgia is better characterized as a healthy psychological resource that helps people navigate current life challenges and build better futures. While most research has focused on personal nostalgia—sentimental reflection on one’s own lived experiences—human sentiment toward the past extends beyond autobiographical memory. People also develop sentimental attitudes about eras they never personally experienced, a phenomenon known as “historical nostalgia.”

Historical nostalgia permeates modern culture. We see it in architectural preservation movements, period-inspired home design, heritage tourism, antique collecting, traditional food practices, and vintage fashion revivals. Newer technologies often serve as vehicles for historical nostalgia, with digital platforms offering tools that recreate analog photography effects, interface designs that deliberately reference earlier media forms, streaming services providing easy access to movies, television shows, music, and video games from earlier decades, and specialized communities formed around shared appreciation for specific historical periods. It’s particularly striking to observe how younger generations who grew up with smartphones, social media, and streaming services are increasingly drawn to analog technologies and pre-digital cultural products.

Businesses have also recognized and capitalized on the power of historical nostalgia. Heritage branding strategies highlight company longevity and tradition, often emphasizing founding dates, original packaging designs, and “since [year]” claims to establish authenticity and trustworthiness. Product designers and engineers frequently draw inspiration from historical aesthetics and functionality, creating hybrid products that blend modern technology with vintage appeal.

This phenomenon also drives creative expression across the arts. Filmmakers craft detailed period pieces that transport audiences to historical eras, while their science fiction movies often incorporate retro-futurism concepts, mixing past and present visions of the future. Musicians incorporate vintage instruments, recording techniques, and stylistic elements from earlier musical periods. Writers and visual artists draw inspiration from historical movements, reinterpreting them through contemporary perspectives. Through these creative works, both creators and audiences engage with perceived values, aesthetics, and lifestyles of times they never personally experienced.

In my book, Past Forward: How Nostalgia Can Help You Live a More Meaningful Life (2023), I discuss over two decades of research my colleagues and I, as well as other scholars, have conducted on the psychology of nostalgia. Nostalgia is certainly a source of retro entertainment as we often have fun revisiting the past. But it is much more than that. Nostalgia is good for psychological and social health. It increases life satisfaction, feelings of belongingness, perceptions of meaning in life, and a clear, positive, and stable sense of self and identity. Critically, when people experience psychological distress or life difficulties, nostalgia has a restorative effect. This is because nostalgia energizes motivation to address current dissatisfactions and pursue goals that improve the situation. For example, when individuals experience loneliness, nostalgically reflecting on past meaningful social experiences reminds them that even though they are currently struggling interpersonally, they are capable of meeting their belongingness needs, which in turn generates the social confidence and motivation required to improve existing relationships or build new ones.

Thus, nostalgia can be understood as a self-regulatory and motivational resource. Indeed, it increases self-confidence, goal pursuit, creative problem solving, and optimism about the future. These psychological growth-oriented states and motivational tendencies are always useful but especially so when people are experiencing life difficulties that undermine well-being, perceptions of personal agency, and goal motivation.

In short, despite involving reflection on the past, nostalgia is fundamentally future-oriented. It helps people draw from past experiences to resolve current challenges and forge a path forward.

In a previous survey conducted by our team at the Human Flourishing Lab, we built upon this large body of behavioral science research by finding that most Americans find nostalgia to be an important psychological resource in their own lives. They view their personal nostalgic memories as meaningful reminders of what matters most, providing comfort during difficult times and guidance and inspiration when facing uncertainty.

Yet we know far less about historical nostalgia and its potential psychological functions. In a qualitative analysis, our team at the Human Flourishing Lab, in partnership with Discover.ai, explored how young American adults are creatively engaging with retro-inspired popular culture and consumer products. However, this research was primarily focused on developing a rich descriptive picture of the ways in which Gen Z engages with historical nostalgia rather than measuring its prevalence. It didn’t assess how common historical nostalgia is among these young adults or the extent to which they consciously view it as a psychological resource. By exclusively examining one generation of young adults, it also did not explore historical nostalgia across different age groups.

To advance our understanding of how common historical nostalgia is among Americans and to what extent they view it as a psychological resource for managing present challenges and future uncertainties, our team at the Human Flourishing Lab conducted a nationally representative survey of just over 2,000 U.S. adults.

EXPERIENCING HISTORICAL NOSTALGIA

To start, we directly assessed Americans’ experience of historical nostalgia by measuring their agreement with the statement: “I feel nostalgic about eras before my lifetime.”

Our findings reveal that historical nostalgia is widespread, with more than two-thirds of Americans reporting feeling nostalgic about eras they never personally experienced. This suggests that nostalgic sentiment extends well beyond autobiographical memory for most Americans. Looking at generational patterns, we find that Gen X and Millennials report the highest rates of historical nostalgia, followed by Gen Z, while Boomers and the Silent Generation report notably lower rates. Men and women report nearly identical rates.

ATTRACTION TO HISTORICAL CONTENT

Another way to understand historical nostalgia is to examine people’s attraction to elements from the past that manifest in their preferences and choices. To assess this dimension, we asked participants to rate their agreement with the statement: “I am drawn to media, styles, hobbies, or traditions that originate from or are inspired by eras before my lifetime.”

Similar to our first measure, more than two-thirds of Americans report being drawn to media, styles, hobbies, or traditions from eras predating their lifetime. This attraction appears strongest among Millennials, followed by Gen Z and Gen X, with substantially lower rates among Boomers and the Silent Generation.

VALUING HISTORICAL IDEAS AND ELEMENTS IN CONTEMPORARY DESIGN

A third approach to understanding historical nostalgia is to examine people’s attitudes toward incorporating historical ideas and elements into new creations. To assess this dimension, we asked participants to rate their agreement with the statement: “I believe that new technologies and products should incorporate ideas and design elements from eras before my lifetime.”

Nearly three-quarters of Americans believe that new technologies and products should incorporate historical design elements, indicating a broad appreciation for connecting present innovation with past traditions. This belief is strongest among Millennials and Gen Z. Notably, even among older Americans who report lower rates of historical nostalgia in our previous measures, a majority believe in incorporating historical elements into new designs.

HISTORICAL NOSTALGIA AS A RESOURCE FOR MANAGING MODERN STRESS

After examining the prevalence of historical nostalgia from multiple angles, we turned to the question of whether Americans consciously utilize it as a psychological resource for managing current challenges. To assess this dimension, we asked participants to rate their agreement with the statement: “When I feel stressed or overwhelmed by modern life, I find it helpful to nostalgically explore cultural attitudes, aesthetics, products, hobbies, or traditions from past eras before my lifetime.”

Nearly two-thirds of Americans report that when feeling stressed or overwhelmed by modern life, they find it helpful to engage with historical nostalgia. This suggests that historical nostalgia, like personal nostalgia, serves as a psychological resource when experiencing negative emotional states. We again observe a generational pattern. Millennials report the highest rate of using historical nostalgia to manage modern stress, followed by Gen X and Gen Z, while Boomers and the Silent Generation report substantially lower rates.

HISTORICAL NOSTALGIA AS A RESOURCE FOR MANAGING FUTURE ANXIETY

Finally, we examined whether Americans utilize historical nostalgia specifically when feeling anxious about the future, which connects to our understanding of nostalgia as ultimately future-oriented. To assess this dimension, we asked participants to rate their agreement with the statement: “When feeling worried or anxious about the future, I find it helpful to nostalgically explore cultural attitudes, aesthetics, products, hobbies, or traditions from past eras before my lifetime.”

Similar to our findings regarding modern stress, nearly two-thirds of Americans report that when feeling worried or anxious about the future, they find it helpful to engage with historical nostalgia. The generational pattern remains consistent, with Millennials most likely to report using historical nostalgia to manage future anxiety, followed by Gen X and Gen Z, while Boomers and the Silent Generation report much lower rates.

CONCLUSION

Our survey findings reveal that historical nostalgia is widespread among Americans, with substantial majorities (68-73%) reporting nostalgic feelings for pre-lifetime eras, attraction to media, styles, hobbies, or traditions from these periods, and support for incorporating historical elements into contemporary design. This extends the concept of nostalgia beyond personal memory, suggesting that humans can develop meaningful sentimental attachments to periods they know only through cultural transmission. Notably, historical nostalgia shows a clear generational divide: Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z consistently demonstrate substantially higher rates across all measures compared to Boomers and the Silent Generation.

Particularly interesting is the strong presence of historical nostalgia among young American adults. Their attraction to media, styles, and traditions from previous eras and their belief that new technologies should incorporate historical design elements suggest that even the youngest adults, who are often described as “digital natives,” find value in connecting with the pre-digital past. This aligns with broader consumer and cultural trends showing younger generations frequently engage with and seek out pre-digital aesthetics, products, and experiences despite growing up in increasingly digital environments.

Similar to personal nostalgia, historical nostalgia appears to function as a psychological resource for many Americans. Most Americans report utilizing historical nostalgia when feeling stressed by modern life or anxious about the future, suggesting it provides comfort, perspective, and potential guidance during challenging times. This is particularly true for Millennials, who consistently report the highest rates of using historical nostalgia as a psychological resource, though Gen Z and Gen X also show substantial utilization of historical nostalgia for managing both modern stress and future anxiety.

While this survey documents the prevalence of historical nostalgia and the belief among many that it serves important psychological functions, further research is needed to understand its precise psychological mechanisms and benefits. Does historical nostalgia ultimately serve similar self-regulatory and motivational functions as personal nostalgia? Does it perhaps offer distinct advantages by connecting people to broader cultural narratives, traditions, identities, and wisdom? Future research is also needed to better understand the generational differences in historical nostalgia documented in this survey and what they might reveal about changing relationships with the past across different age groups.

Research indicates that personal nostalgia promotes psychological states and behaviors that support human progress, such as self-efficacy, open-mindedness, optimism, creativity, and goal-focused motivation. Might historical nostalgia also contribute to progress, but perhaps in unique ways? For instance, a recent survey from the Human Flourishing Lab finds that most Americans feel grateful for the progress made by previous generations that make life better today and believe it can offer guidance and inspiration for current aspirations to improve the world of tomorrow. As individuals increasingly find themselves navigating rapidly changing technological and social landscapes, and many envision a future of division, decline, and despair, might historical nostalgia help people connect more deeply with past achievements, potentially reinforcing belief in human capacity for positive change and inspiring mindsets and actions that advance progress?

As technological developments continue to change how we live, work, consume, and connect, many Americans find themselves drawn to perspectives and approaches from previous eras. However, Americans, especially younger generations, also tend to enthusiastically embrace technological and cultural innovation. This suggests that interest in the historical past reflects not a resistance to change, but rather a creative integration of old and new. By developing a deeper understanding of historical nostalgia, we may better appreciate how connecting with the past can help guide and energize our efforts to navigate an increasingly complex and rapidly changing world and build a better future.

METHODOLOGY

This survey was conducted online within the United States by The Harris Poll on behalf of the Human Flourishing Lab from March 25-27, 2025, among 2,085 adults ages 18 and older. The sampling precision of Harris online polls is measured by using a Bayesian credible interval. For this study, the sample data is accurate to within +/- 2.5 percentage points using a 95% confidence level. For each of the five survey items previously described, respondents were asked to indicate whether they strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, or strongly agree with each prompt.

Clay Routledge, PhD, is Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer (COO) at the Archbridge Institute, where he also leads the institute’s Human Flourishing Lab. As a thought leader in existential psychology and human motivation, Clay translates research into practical insights that help people reach their full potential, build meaningful lives, and advance human progress and flourishing. Dr. Routledge received his Ph.D. in psychology from the University of Missouri-Columbia. He is co-editor of Profectus Magazine, an online publication dedicated to human progress and flourishing. He writes the weekly newsletter "Flourishing Friday."