Key Points

Over the past several decades, the nature of the economy has shifted from a goods-based economy to a service-based economy. This shift has also changed the kinds of skills most sought after and rewarded in the labor market.

- Soft skills, also known as character, socio-emotional skills (or social-emotional skills), and non-cognitive skills, have become essential for success in the modern economy.

- With new technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) poised to further revolutionize the workplace, soft skills will likely become more important in the coming years.

- Soft skills are developed from an early age, particularly in healthy and stable families. Social environment and practice with social interaction also play key roles in their development.

- Free play and independent activity are significant drivers of soft skill development. Currently, both policy and culture hinder these activities, and lifting those barriers is an essential task in

- Ensuring an environment in which children are able to cultivate the soft skills necessary to succeed in both work and life.

The Modern Labor Market

In December 2022, Jasmine Cheng launched a boutique recruiting firm, TopKnack, and later explained to Business Insider how an unconventional work partner helped her save “a minimum of 10 hours a week.” In an industry most frequently associated with forging strong personal connections and relationships with clients and potential employees, Cheng explained how she used a version of OpenAI’s Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPTs), a large language model (LLM) artificial intelligence (AI) known as ChatGPT, to automate advanced search queries, write first drafts of basic job descriptions, generate interview questions, create lists of potential client companies, and more. Using ChatGPT allowed Cheng to save time by automating certain aspects of the job and afforded her more time for others. Rather than replace her job entirely, Cheng explained how integrating AI into her workflow allowed her to work better and more efficiently.

While Cheng may be an early adopter of AI, her story is far from unique. Other professions, industries, and entrepreneurs are coming up with ways to use LLM AI tools to make their jobs more efficient and their business endeavors more successful. Despite some reasonable concerns—and even some hysterical fears—about a coming wave of mass human unemployment in favor of “The Machines,” the more probable outcome will be the integration of both human work and advanced AI tools, like ChatGPT. These types of AI tools may be the most advanced and recent type of labor-saving capital to-date, and they are genuinely impressive in their capabilities, but the history of work is full of such labor-saving innovations—along with their attendant fears about human labor being replaced.

In each case, new innovations have shifted the nature of work and significantly changed the labor market. Some jobs were eliminated, while others were created. Productivity increases due to technological change in agriculture, for example, meant that a greater share of people were able to find new and different kinds of employment opportunities. More recently, the digital revolution has enabled a dramatic rise in productivity within pre-digital jobs as labor-saving tools were integrated into tasks and workflows. It’s a safe bet that the labor market of today, and especially of the near future, will be particularly rewarding for those who are successfully able to integrate such tools into their enterprises.

The coming period of adjustment may be more or less widespread across the economy, and its duration is uncertain, but just as in the past, those able to adapt to technological innovations will remain in high demand relative to their peers. Furthermore, not only will jobs and tasks change but so will the skills necessary to succeed. Skills are the bedrock human capital that allow individuals to see opportunities, find efficiencies, and generally reach success in delivering the products and services necessary to best meet the needs of employers and, ultimately, serve customers. The new tools now coming online seem best suited to take over routinized and fact-driven tasks currently completed by human labor. In this way, such tools are a much more powerful extension of the workforce transformation that has been taking place for decades.

From Goods to Services

Beginning as early as the late 1950s, new technologies, particularly advanced and innovative physical capital, have replaced the need for human labor in a variety of routinized and repetitive physical tasks. The crowded assembly lines of the past have been replaced with impressive machines and technical equipment that have greatly boosted the productive capacity of producers of physical goods. Nowhere has this shift been more apparent (and caused as much consternation) as in the manufacturing sector.

Continuing through the present, it is often politically popular to claim that the United States has outsourced its physical productive capacity or that the manufacturing sector has been decimated. The culprit in these narratives is often a vague “globalism” or sometimes a more specific belief that free trade agreements that more easily allow the import and export of goods have decimated US manufacturing. Despite their surprising popularity, these narratives do not match the facts. While it is true that liberalized trade policies had an effect on US manufacturing, the majority of these changes are a result of technological advancements that have allowed fewer workers to maintain the same or even greater output.

For example, in a 2015 paper published by the American Economic Association, the authors found that the US Steel Industry “shed about 75 percent of its workforce between 1962 and 2005, or about 400,000 employees.” However, due to technological innovations that allowed for significant increases in productivity, this major decrease in employment was not coupled with a corresponding decrease in output. A 2021 analysis of the decline in employment in the manufacturing sector from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) concluded that “the bottom line is that almost the entire decline [of manufacturing employment] from 32 percent of the labor force in 1955 to 8 percent in 2019 was not caused by imports but by higher productivity.” Similarly, a 2018 paper from the Urban Institute concludes by noting that “rather than being a victim of foreign trade, manufacturing employment has been a victim of its own success: increased productivity has meant that fewer workers are required to produce more output.”

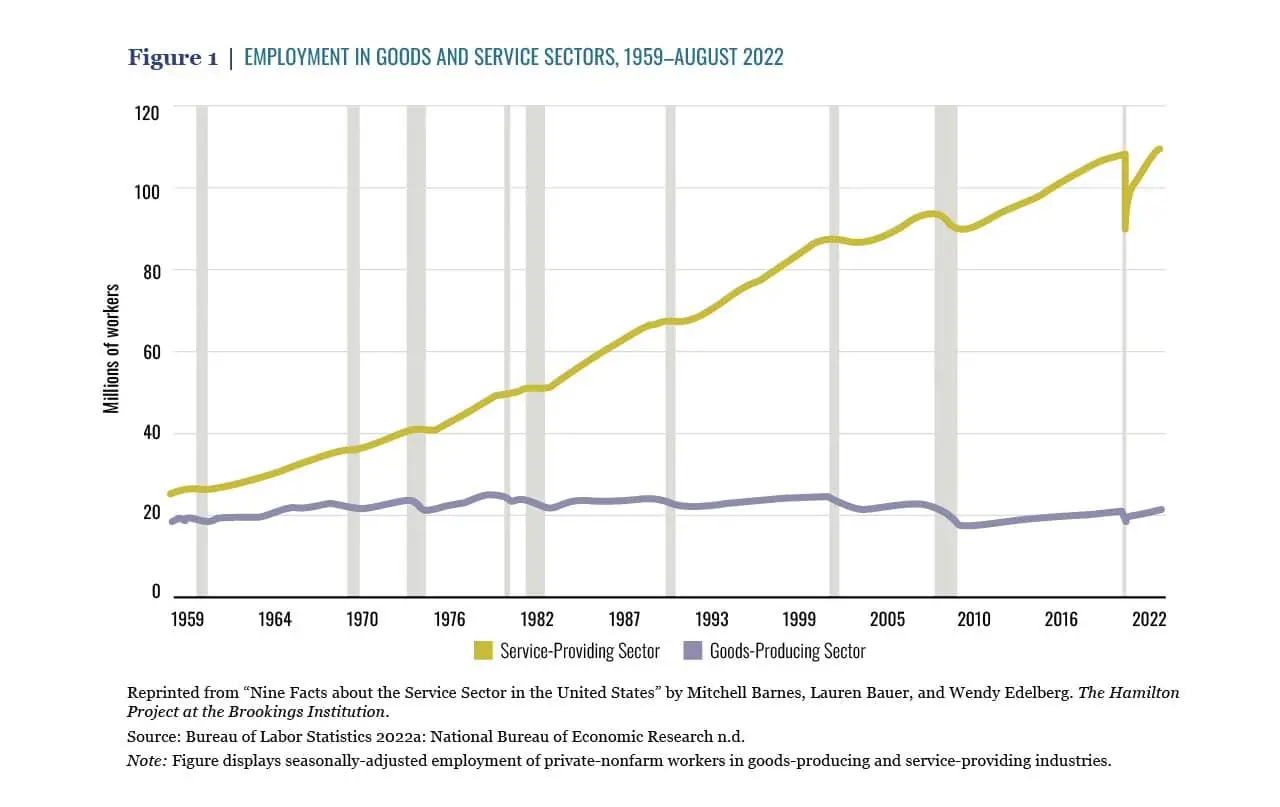

This decline in manufacturing employment, spurred by advances in physical capital that enabled much greater productivity, did not spell mass unemployment, however. Instead, many of those displaced workers, and especially those who may have otherwise gone into the sector, found new and different ways to use their skills that were less dependent on repetitive physical labor. The primary result of these advancements in productivity within the goods-producing economic sectors meant that an increasingly large portion of employment became less centered on the production of physical goods and more related to the delivery of services. According to a 2022 report from the Brookings Institution, “Goods-sector employment peaked at 25 million in 1979. In that year, service-sector employment was already higher at 49 million; since then, it has grown to be 109 million.”

As this shift in the economic landscape was occurring, the skills needed to succeed in the labor market were also changing. The demand for physical strength or tolerance for repetition were replaced by a need for technical knowledge and interpersonal skills. Educational fields that emphasized Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) were becoming increasingly important in equipping workers with the skills necessary to succeed. But coupled with these “cognitive” skills, another set of skills also began to catch the attention of employers, economists, and scholars studying the labor market. These skills were less conducive to traditional forms of education and detection in standardized testing but were instead more social and psychological in nature. In contrast to the “hard skills” emphasized in technical education, these “soft skills” quickly became essential skills for a modern workplace in which workers were expected to work in teams, solve complex problems, frequently learn new things, and think creatively, both by themselves and with others.

Understanding soft skills, what they are, and most importantly, how to cultivate them, should be a top priority for anyone interested in ensuring that the next generation of workers has the tools necessary to succeed in our rapidly changing economic landscape. New AI tools are likely to follow previous patterns of technological innovation and replace the need for human labor in the realm of today’s repetitive or routine cognitive tasks. As such tasks come to be completed by non-human capital, human labor will be reallocated toward the tasks that such tools cannot complete well on their own, such as the creative, conceptual, and relational.

Soft Skills

While economists and academics have yet to fully settle on a single definition of non-cognitive, character skills, or “soft skills,” there is general agreement on the substance of the term. Sometimes called non-cognitive skills, because the term refers to those skills not adequately captured by standard aptitude or achievement tests, the term “soft skills” refers to a range of personality traits, communication, and socio-emotional and interpersonal skills that can be loosely categorized as a broad set of skills, competencies, behaviors, attitudes, and personal qualities that enable people to effectively navigate their environments, work well with others, self-regulate, and achieve their goals.

Owing at least in part to the way in which soft skills as a category remain difficult to precisely define, educators and scholars continue to experiment with the best ways in which to equip students and workers with these essential skills. However, despite these challenges, there exists a broad body of research that demonstrates their importance to successfully navigating the labor market. Given such robust evidence for their significance, finding effective ways in which to impart and develop these skills is a critical task for educators, employers, policymakers, and workers themselves.

Evidence for the Growing Importance of Soft Skills

In contrast to hard skills—which are often technical, narrow, and specifically related to a particular subject area, tool, or process—soft skills emphasize the socio-emotional and interpersonal skills needed to both internally self-regulate and work well with others. As the category of soft skills entered the academic literature, a procession of studies has found that such skills have played an increasingly significant role in predicting labor market (and financial) success.

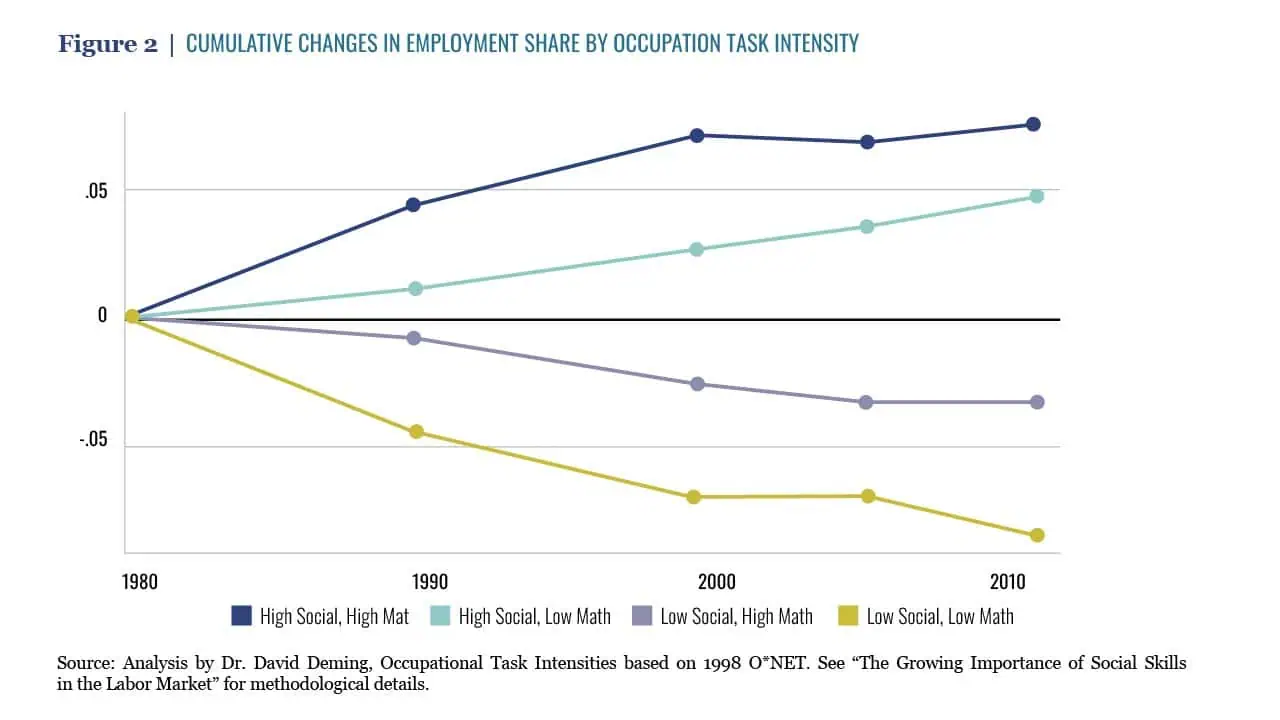

A 2014 analysis from Tim Kautz, James Heckman, and others found that the predictive power of soft skills in terms of various outcomes “rivals or exceeds that of cognitive skills.” Furthermore, in his seminal 2017 paper on the topic, Harvard economist David Deming identified a clear trend in employment opportunities favoring soft skills compared to hard or cognitive skills. Specifically, Deming found the following:

Between 1980 and 2012, jobs requiring high levels of social interaction grew by nearly 12 percentage points as a share of the U.S. labor force. Math-intensive but less social jobs—including many STEM occupations—shrank by 3.3 percentage points over the same period. Employment and wage growth were particularly strong for jobs requiring high levels of both math skill and social skills.

These findings demonstrated a significant increase in the demand for workers with strong social skills. While the highest wages and most employment opportunities were available to workers with both social skills and math (cognitive) skills, the opportunities for those with low math skills but high social skills exceeded those of workers with high math skills but low social skills.

Since Deming’s seminal paper, other researchers have continued to find increased labor market returns for soft skills as compared to hard skills. Further work from Deming and Kadeem Noray, summarized by Noray, found the following:

From 2007 to 2019, the proportion of online job ads that include at least one character skill increased by 12.7 percentage points and the proportion of ads that include at least one social skill increased by 11.4 percentage points. In comparison, the proportion of ads that include at least one cognitive skill increased by only 8.5 percentage points.

As recently as 2022, Swedish researchers Per-Anders Edin, Peter Fredriksson, and their coauthors found that “between 1992 and 2013, the economic return to noncognitive skill—a psychologist-assessed measure of teamwork and leadership skill—roughly doubled.” Moreover, after conducting a thorough literature review of the evidence for the labor market value of soft skills (character skills, in his words) and building on the work of economist David Autor, Noray sums up his view of skills and the labor market this way:

To summarize, in the past three decades, computers and software have entered and filtered through the economy, making many routine cognitive occupations unnecessary. Workers in jobs that require more flexibility, complexity of thought, and tacit knowledge have proved difficult to codify and therefore difficult to replace. Furthermore, computer technologies have made workers with these types of skills relatively more productive. Together, these forces seem to have reduced the relative demand for cognitive skills and increased the relative demand for character skills.

In addition to the strong academic research demonstrating the growing value of soft skills, employers are making it increasingly clear that soft skills are a key priority when recruiting and hiring new workers. A 2023 LinkedIn report based on an analysis of their 800 million global users hiring and job posting data over the previous six months found that the top five most in-demand skills were management, communication, customer service, leadership, and sales.

The push toward valuing soft skills ranges from those who deal with entry-level applicants to the executive level. A 2018 Deloitte survey of 1,116 Chief Information Officers found that creativity, cognitive flexibility, and emotional intelligence were the three skills that respondents said were most likely to “grow significantly in importance during the next few years.” Meanwhile, in a 2017 Wall Street Journal profile discussing his decades in finding people work, Bob Funk, Chairman, CEO, and founder of Express Employment Professionals, one of the nation’s largest job agencies, outlined the importance of soft skills:

Start with skills. Hard skills and experience, he says, are only half the equation, and not the important half. He shares a small brochure his company puts out summarizing a recent survey of employers. “So many people do not realize how important the soft skills are to unlocking job opportunity,” he says.

In order, the survey found the top five traits employers look for are as follows: attitude, work ethic/integrity, communication, culture fit, critical thinking.

Up and down the labor market, through rigorous academic research and in employer surveys, the importance of soft skills is difficult to overstate. Given the recent shifts in the economy and the technology now making its way into the workplace, there are several reasons why these trends are likely to continue or even become more pronounced.

The Future of Work Is Powered by Soft Skills

The most significant technologies poised to alter the nature of work are the AI tools, such as OpenAI’s Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPTs), now coming online. While it’s too soon to predict precisely how these tools will affect the workforce in detail, which jobs they will affect, how dramatically, and how quickly such tools will be adopted, there is little doubt that the innovative technology will prove transformative.

However, while some jobs may be fully automated with these tools, the majority of “exposed” jobs are likely to be augmented by AI rather than fully replaced by it. According to a report from OpenAI, the company responsible for ChatGPT, only 20 percent of jobs are “fully exposed” to AI, meaning that they are at risk of being replaced by the technology. The other 80 percent are “partially exposed,” meaning that such jobs are likely to integrate some form of AI into their tasks and workflow but are less likely to be fully replaced.

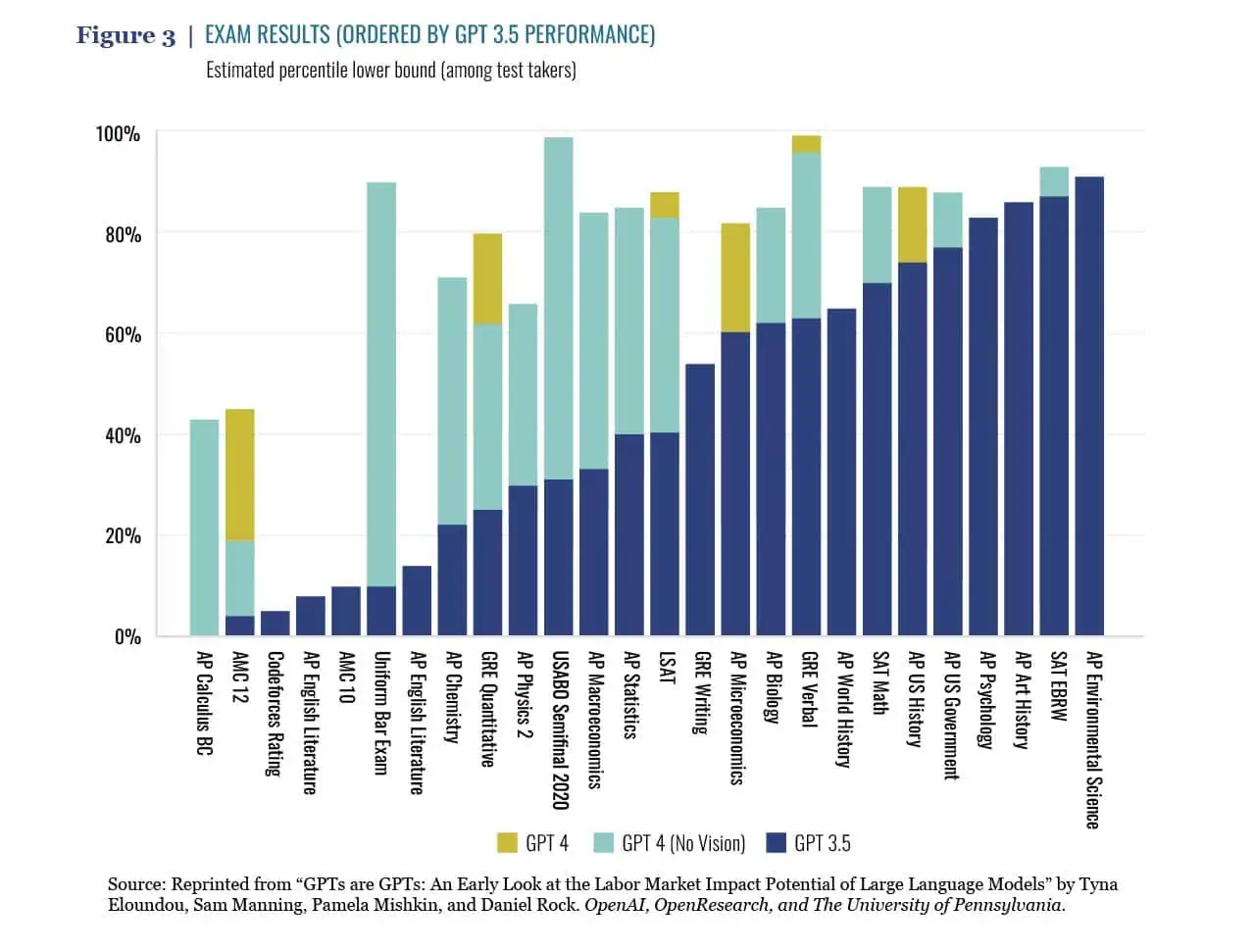

To get a sense of which jobs and tasks these AI tools are most likely to influence going forward, the researchers at OpenAI gave different versions of their ChatGPT models various professional examinations to complete. The results can be seen in Figure 3. While the AI models did not score particular well on exams for Advanced Placement (AP) English Literature or AP English Language, scoring well below the 20th percentile on both exams, the models scored well above the 80th percentile on exams such as the Uniform Bar Exam taken by lawyers and the GRE verbal exam. While AI models continue their refinement and improvement, having a sense of how well the models generally score on these kinds of professional and academic exams can provide useful insight into how such tools might or might not be effectively deployed into the workforce in the near future.

As certain tasks that rely on mastery of a particular subject matter or are heavily routinized in some way become automated, the skills needed to successfully complete the other parts of a given job will become relatively more important. Tasks that require skills such as creative thinking, problem solving, and interpersonal communication are not as easily automated and are key areas in which employers are likely to be most interested when thinking about meeting their workforce needs. Indeed, in a recent report from the US Chamber of Commerce’s Commission on Artificial Intelligence Competitiveness, Inclusion, and Innovation, the authors specifically note the importance of such skills in effective workforce development:

The curriculum could also emphasize critical thinking, problem solving, and other skills difficult to automate and resilient to changing requirements. As [AI researcher] Stefania Druga suggested at the Palo Alto hearing, “. . . instead of teaching people skills that will eventually be automated, we should teach young people how to become better at problem solving, how to develop creative thinking, and how to interact and collaborate with machines and come up with new creative ideas and applications that cannot be automated.”

Because most of these technologies have yet to be adopted at scale, specific recommendations regarding precisely which skills are best suited to successfully integrate such tools into typical jobs are difficult to predict. Despite this obstacle, there is a growing consensus around some general types of less-readily automatable skills that provide a starting point for educators and policymakers to consider as new technologies enter the realm of workforce development strategies. So far, these basics tend to include the exact kinds of soft skills that have already become important to workplace success over the past several decades.

In fact, a recent study from Lightcast, which assessed more than 1.3 million job postings for entry-level workers with a bachelor’s degree, found that “the ability to communicate” was the most desired skill requested by employers. In an interview with Axios, Lightcast senior economist Rachel Sederberg summarized their findings, saying, “There are certain things that AI can’t do, [a]nd those are going to be increasingly important.”

While new technologies and innovations in the types of ways in which jobs are done are a leading reason why soft skills will continue to grow in importance, there are other ways in which the labor market has already changed to require a greater mastery of these skills. Getting a job or even an interview is increasingly based on these skills. Even with all of the new ways in which companies and job seekers can post open positions or search through job applications and resumes using sophisticated online resources, research suggests that “up to 70 [percent] of all jobs are not published on publicly available job search sites, and research has long shown that anywhere from half to upwards of 80 [percent] of jobs are filled through networking.”

Cultivating a professional network and developing relationships with colleagues, coworkers, and other industry professionals is an endeavor that can pay massive dividends when it comes to learning about new potential opportunities. For those new to an industry, this could mean participating in student or academic clubs and organizations or seeking internships with established firms. For those already working in a particular field, this might mean making the effort to go to conferences, engaging in professional networking, or participating in industry organizations and events. Cultivating soft skills is an essential part of building and creating relationships and making the most of these endeavors. Not only are such skills helpful for on-the-job tasks, they are also important to building a professional network. Moreover, as workers continue changing jobs at a higher rate than in the past (although this slows down as workers age and become more established), knowing about new opportunities has increased in importance.

It remains true that the best way to climb the income ladder is through a job; and success in the modern labor market increasingly depends on soft skills. These skills are also poised to become even more important given the technological changes that appear just around the corner. Developing and cultivating these skills is important for every worker but should be a top priority when it comes to thinking about what preparation should include for those who will be entering the workforce in the coming years.

Building Soft Skills

Unlike fact-based hard skills, soft skills (or non-cognitive, socio-emotional, and character skills) are relatively more difficult to measure and impart in a rigorous and systematic way that can be easily empirically verified. There are ways in which soft skills are measured, but rarely do such methods reflect the same confidence as an analysis based on standardized tests or well-designed randomized controlled trials. While this presents a challenge for researchers accustomed to more discrete tools of evaluation, the development of such skills is too crucial an ingredient for success to be derailed by the need for relatively more difficult methods of evaluation. Still, there is some promising research into methods effective in developing soft skills, and it’s important to note that individuals begin their development at very early ages, building on them as they grow older.

Early Childhood Interventions

One of the most robust and frequently cited early childhood interventions aimed at boosting soft skills is the Perry Preschool program. The program began in the early 1960s and provided three- and four-year-old black children with IQ scores below 85 at age three with 2.5 hours of center-based preschool programming five days per week and home visits designed to increase non-cognitive skills. The program also tracked a control group of students who were from the same demographic and attended the same school as program participants. Researchers followed up with participants at ages 19, 27, and 40 and concluded that program participants experienced better outcomes in terms of income, family life, and crime than their peers.

The program’s inclusion of a control group and detailed follow-up analysis years after the completion of the intervention makes it one of the most reliable studies about the effects of non-cognitive skills and the ways in which they might be enhanced. Moreover, researchers were able to conclude that the positive observed results from the intervention were due to the cultivation of non-cognitive skills such as improved teacher-reported instances of “externalizing behavior,” higher levels of academic motivation, and a higher degree of openness. The attribution of these outcomes to improvements in non-cognitive skills is based on the fact that while IQ did increase in the short-term following participation in the program, those effects faded over time.

Other early childhood interventions, such as Head Start (preschool) programs and nurse home visiting programs like the Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP), in which nurses visit low-income mothers pregnant with their first child and offer guidance through the child’s second birthday, also show positive results in improved life outcomes. In particular, researchers analyzing Head Start programs find that improved outcomes are likely due to the development of non-cognitive skills, as the improvements in cognitive skills (like math) typically fade over time. There are also some interventions geared towards developing soft skills in adolescents, but while some of those programs are promising, none yields the kinds of benefits that earlier interventions do and often play the role of remediating soft skill deficits from earlier in life. To the extent that soft skills are developed in adolescence or early adulthood, there is strong evidence to suggest that early work experience is highly effective in doing so.

Economists Tim Kautz and James Heckman have been at the forefront of measuring non-cognitive skills and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions aimed at fostering them. In a landmark 2014 paper examining the efficacy of non-cognitive skill-boosting interventions, Kautz, Heckman, and their coauthors explain how building such skills early is important: “Skill development is a dynamic process. The early years are important in shaping all skills and in laying the foundations for successful investment and intervention in the later years.” While the authors note the benefits of high-quality early interventions to boost non-cognitive skills, particularly beneficial for disadvantaged children, they also emphasize that such skills are fundamentally shaped by families, schools, and social environments.

Family, in particular, seems to be of the greatest importance when it comes to the development of soft skills early in life. In summarizing their research, Kautz, Heckman, and their colleagues explicitly note that “successful interventions at any age emulate the mentoring and attachment that successful families give their children.”

The Importance of the Family

Because soft skills have less to do with facts and more to do with social interactions, socio-emotional skills, and self-regulatory habits, it shouldn’t be surprising that family dynamics shape these skills from an early age. The behavioral models provided by parents, siblings, and extended family are ever-present and exist well before a child can begin learning more formally. Even several of the beneficial external interventions to boost soft skills are geared towards parents and designed to offer guidance for parents in their efforts to create a stable, nurturing, and successful family life.

Perhaps the most outspoken proponent of the importance of family life in skill development, economist James Heckman made his conclusions clear in a 2020 interview, saying the following:

The family is the source of life and growth. Families build values, encourage (or discourage) their children in school and out. Families—far more than schools—create or inhibit life opportunities. A huge body of evidence shows the powerful role of families in shaping the lives of their children. Dysfunctional families produce dysfunctional children. Schools can only partially compensate for the damage done to the children by dysfunctional families…

The “intervention” that a loving, resourceful family gives to its children has huge benefits that, unfortunately, have never been measured well. Public preschool programs can potentially compensate for the home environments of disadvantaged children. No public preschool program can provide the environments and the parental love and care of a functioning family and the lifetime benefits that ensue.

Even when considering the effects of universal social policies, such as those found in Denmark and often discussed as potential a model for the US, the vital importance of the family is apparent. In recent research with Danish economist Rasmus Landersø, Heckman analyzed the causes of Denmark’s low income inequality and high intergenerational economic mobility. They found that these outcomes were a result of the Danish tax and transfer payment systems much more than a result of more effectively developing human capital or successfully building skills across generations. Rather, a key takeaway from the examination was the extent to which families shaped child outcomes and the utilization of the universally available public programs.

Given the vital importance of families in developing the skills necessary for success in education and later in life, the decline in the proportion of children growing up in stable households with two married parents is discouraging. In 1960, only about 5 percent of children were born to unmarried mothers. Since 2008, that percentage has risen to about 41 percent. It’s true that in some of these cases, the parents may not be married but are instead cohabiting. While this may be a better environment in which to temporarily maintain stability and help children develop skills early on, two-thirds of cohabiting parents will break up before their child turns 12 (compared to a quarter of married parents).

Strengthening the stability of families has many benefits, but it is seldom considered an important factor in effective workforce development. For policymakers interested in enabling children to learn important skills that will help them succeed throughout their lifetimes, strengthening marriage should be a priority. Simply removing the many public policy dis-incentives to marriage would be a good starting point. Eliminating marriage penalties embedded in social safety net programs, such as childcare assistance, would be a significant step in the right direction. Reforming safety net programs to eliminate the strong marriage penalties for the “near poor” would also be a welcome reform for those interested in ensuring more children get the chance to build the skills necessary for lifelong success.

In summary, when it comes to building soft skills, there are several broad conclusions that have been strongly demonstrated by the academic literature. First, soft skills are developed early, beginning in the first years of a child’s life, building on one another, and enabling early success that can be carried through life. Second, while such skills can be imparted when children reach adolescence or even adulthood, this is generally more difficult and more expensive. Finally, family is an essential incubator of skills, particularly the soft skills necessary to learn the more cognitive, fact-based skills later on.

These are valuable conclusions based on a robust body of research, but they by no means represent an exhaustive list. In fact, beyond family life and school or educational-based interventions, social environment is a key factor in soft skill development that parents and policymakers must keep in mind.

Focus on Free Play

While families might be the first incubators of soft skills, social environments outside the family are also critically important. Peer groups and the opportunity to interact socially with others in a variety of contexts is the practice that is needed to build and develop skills like teamwork, perseverance, creativity, and problem solving. Experiencing social environments is a necessary prerequisite to learning how to successfully navigate them. Nowhere has the natural opportunity to develop important life skills eroded more than with the decline in childhood free play. Fortunately, this also means that recovering childhood free play could yield an enormous increase in the capacity for children to build the tools necessary to succeed in education and in life.

Free Play and Soft Skills

Free play is exactly what it sounds like: play that is undirected and independent in nature. Often free play means a lack of adult supervision and involves kids playing in groups with their peers—typically with a mix of different ages. Free play isn’t just a phrase to describe kids having fun on their own; it’s also an important psychological activity whose roots are biologically ingrained in human beings and which serves an extremely important developmental purpose. Psychologist and former Boston College professor Peter Gray, author of the book Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life, summarizes what he means by the phrase “free play” as follows:

Free play is the means by which children learn to make friends, overcome fears, solve their own problems, and generally take control of their own lives. It is also the primary means by which children practice and acquire the physical and intellectual skills that are essential for success in the culture in which they are growing. Nothing that we do, no amount of toys we buy or “quality time” or special training we give our children, can compensate for the freedom we take away. The things that children learn through their own initiatives, in free play, cannot be taught in other ways.

In other words, free play is an activity in which children acquire and develop soft skills. When kids are playing, they are engaged in a constant stream of social activity that requires practicing social skills like cooperation, decision-making, and paying attention to others. Because play isn’t a forced activity that children must engage in, if too many players get frustrated, they’ll quit, and the game ends. This fosters a cooperative environment in which decisions have to be made in concert with others. Patience, compromise, negotiation, and calibrating activities to varying capacities of those involved are all skills that are built and practiced during free play.

This kind of social practice has benefits for kids of all ages and skill levels as well. Younger children learn to regulate their emotions to keep playing while learning new things by observing their older peers. Older children practice leadership skills and hone their own knowledge and skills by teaching their younger peers. Gray documents how these patterns trace their origins far back into human history but are just as present on the modern playground. He notes, “In free play, children learn to make their own decisions, solve their own problems, create and abide by rules, and get along with others as equals rather than as obedient or rebellious subordinates.”

The “free” part of free play is the component that sets it apart from other kinds of activities. Free play is definitionally removed from the confines of rigid rules, such as the kind found in organized sports, or from constant parental supervision and interference. Rather, free play is independent, child-directed, and based on both interest and joy. The important development that occurs during free play is precisely because of that independence. Gray provides an illustrative example:

Once I was watching some kids play an informal game of basketball. They were spending more time deciding on the rules and arguing about whether particular plays were fair than they were playing the game. I overheard a nearby adult say, “Too bad they don’t have a referee to decide these things, so they wouldn’t have to spend so much time debating.” Well, is it too bad? In the course of their lives, which will be the more important skill—shooting or debating effectively and learning how to compromise? Kids playing sports informally are practicing many things at once, the least important of which may be the sport itself.

While they don’t realize it in the moment, children engaging in free play are building skills that will help them successfully navigate a rapidly changing labor market. In a 2021 working paper, Harvard economist David Deming describes the key finding of his research about decision-making in the workplace:

Modern jobs increasingly require workers to adapt to unforeseen circumstances and to solve abstract, unscripted problems without employer oversight. As automation technology progresses, machines can increasingly perform many pre-scripted tasks better than a person, which leaves non-routine, open-ended tasks as the domain of human labor.

Just as with decision-making skills, interpersonal skills developed during free play are laying the foundation for effective teamwork later in life. The emotional self-regulation and self-control skills that are developed as part of free play are important skills increasingly sought after by employers seeking to hire self-directed employees who can function well without needing stringent oversight. Moreover, free play can be an important mechanism for building the kinds of beneficial mental health habits and resources that are becoming increasingly important in the workplace.

Free Play, Independence, and Mental Health

Over the past several years, American children and teens have seen rates of mental health concerns rise dramatically. Between 2007 and 2019, the percentage of adolescents reporting a major depressive episode increased by 60 percent. Furthermore, in 2021, 44 percent of American high school students reported “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness,” an increase from 26 percent in 2009. The social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has documented the rise in mental health concerns among college undergraduates, noting that their rate of anxiety has increased by 134 percent since 2010. Unsurprisingly, businesses are finding themselves concerned about these trends as they seek to recruit new employees into the workforce.

Human resources departments are finding themselves overwhelmed by the scale of employees coming to them to help with mental health concerns. Many businesses have set up Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) to work with employees experiencing mental health issues. Dan Schawbel, managing partner at Workplace Intelligence and research director at Future Workplace, an executive development firm, has predicted that “managers and HR professionals will either need to become stand-in counselors before referring employees to professionals, or hire onsite therapists to deal with mental health issues immediately, rather than wait for a worker to go through an EAP system that can be time-consuming.” Research from the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) has even found that, in 2023, “61 percent of Generation Z respondents said they would strongly consider leaving their current job if offered a new one with significantly better mental health benefits.”

While this can be seen as a positive sign that businesses are responding to the mental health needs of their younger employees, those interested in building effective skills for the workplace should also consider ways in which young people become more resilient and enter the workplace with better mental health. In addition to building the kinds of soft skills that are rewarded in the modern labor market, free play can also help children develop the practices, habits, and skills that contribute to good mental health.

Peter Gray has been at the forefront of psychological experts sounding the alarm that recent trends in parenting are, at least in part, negatively affecting the mental health of today’s kids and teens. “One thing we know for sure about anxiety and depression,” he says, “is that they correlate strongly with people’s sense of control or lack of control over their own lives.” Gray’s points were echoed in a 2017 essay in Reason Magazine by Lenore Skenazy and Jonathan Haidt. They document how the rise in “helicopter parenting” became a key reason why kids are missing out on the free and unsupervised play that lets them experience and deal with failure and rejection but also with earned success and the confidence that comes with the ability to adapt to changing circumstances. Instead, a culture of safety and extreme competitive achievement has crowded out these experiences, depriving kids of these crucial stepping stones toward adulthood. Now, when kids finally do leave the home or experience failure, they are left unprepared and without confidence in their ability to handle challenging situations.

Fortunately, this perspective is gaining popularity and has even made its way into some clinical practice. Dr. Camilo Ortiz, a clinical psychologist and Flourishing in Action Fellow with the Archbridge Institute, describes his treatment for children experiencing anxiety—namely, large doses of independence. Ortiz explains his reasoning:

When parents hover and prevent children from independently exploring the world around them, they foster many of the processes that scientists have identified as causes of anxiety. Kids who don’t practice independence (yes, it is a skill that withers without practice) are less self-confident, have worse social skills, are less tolerant of uncertainty, have worse problem-solving skills, and are less resilient. They overestimate danger, underestimate their own ability to handle problems, and catastrophize when things don’t go as expected. Kids need lots of practice with what I call the four Ds: discomfort, distress, disappointment, and (mild) danger. When parents step in to “save” children from the four Ds, they inadvertently weaken children’s ability to successfully navigate these integral parts of life. In contrast, independence is a fantastic way for kids to get this practice and without even realizing it, inoculate themselves against anxiety.

Ortiz goes on to explain how he and his colleagues work with kids and parents to develop plans for Independence Activities (IAs) that allow kids the opportunity to build that resiliency by doing things on their own. Despite the growing consensus that letting kids have opportunities for unsupervised free play and independence is best, Ortiz points out that the most challenging barrier has been adults; and not the ones you might think: “We’ve never had a stranger try to harm a child practicing independence; on the other hand, we’ve seen plenty of anxious strangers stepping in to “protect” our kids by trying to stop the independence activity,” he said.

The challenge facing Ortiz, his clients completing their independence activities, and any parent who might be willing to give their kids the independence necessary to develop these important life skills is a familiar one. Simply put, they face an uphill battle against both a culture and a public policy status quo that makes such activities difficult or, in many cases, illegal.

Trending Away from Free Play and Reasonable Childhood Independence

Given the importance of soft skills for future success, the contrast between the unstructured and independent nature of free play and the regimented top-down methods of most modern schools—and childhood routines more broadly—is stark. Peter Gray spends considerable time tracing how modern schools fail to provide kids with the opportunity to develop in any way close to the way in which free play can. Compulsory attendance, age segregation, and constant supervision are the antithesis of how kids had successfully learned to navigate life in the past. But it’s not just schools that fail to recognize these essential learning opportunities.

In documenting the way in which safety culture has permeated modern parenthood, Skenazy and Haidt document how kids are more supervised than ever in spite of the fact that rates of childhood abduction or violence are at all-time lows. Even with some recent increases in crime over the past couple of years, crime rates are still well below the rates of the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s. Skenazy and Haidt reserve judgment against any single parent, instead pointing out that we’ve seen something of a downward spiral in unhealthy levels of constant childhood supervision, noting, “When all the first-graders are walking themselves to school, it’s easy to add yours to the mix. When your child is the only one, it’s harder. And that’s where we are today.”

In 2019, The New York Times upped the ante from mere helicopter parents by highlighting the rise of the so-called snowplow parent. “Some affluent mothers and fathers now are more like snowplows: machines chugging ahead, clearing any obstacles in their child’s path to success, so they don’t have to encounter failure, frustration or lost opportunities.” Given what we know about skill development and mental health, these trends do not inspire a great deal of confidence in the ability of such children to successfully navigate life—even if their parents ensure that they secure admission into a top-rated university.

In many ways, these trends are the culmination of cultural movements that range in origin from paranoia about child abduction to hyper competitiveness in the realm of college admissions. However, perhaps even more distressing has been the application of the law in cases relating to childhood independence. Even in instances in which parents grant their kids or teens the freedom to engage in independent activities or free play, the police or child protective services have never been more likely to step in.

Lenore Skenazy’s excellent organization, Let Grow, has been at the forefront of highlighting and working to reverse these trends and give kids the room to, well, grow. As part of that work, Skenazy hears from parents all over the country and documents many of these cases on her organization’s website. To get a sense of what parents are up against legally, here are just a few cases:

- After neighbors called the police, a mother in Port St. Lucie, Florida was arrested for letting her seven-year-old son walk to the park by himself. The park was less than a half a mile from their home, was on a familiar route, and he had a cell phone with him.

- In Teaneck, New Jersey, parents let a seven-year-old walk around the block by herself. Police were called, escorted the girl home, and when the parents declined to provide identification to the police, the father was arrested on the charge of “obstructing justice.” The police report states that “the father attempted to prevent the police from taking his daughter into protective custody.” He was later released and fined $133.

- A working mother in South Carolina was arrested after she let her nine-year-old daughter play at a park six minutes away from their home while she worked at a nearby McDonalds. The child had a key to the house and a cell phone. ,

- A mother was arrested on charges of criminal reckless conduct when she let her fourteen-year-old daughter babysit her younger siblings while she went to work. This was in 2020 when daycares were closed and the police were called when her four-year-old went outside to play with his neighbor and was unsupervised for ten to fifteen minutes. Thankfully, years later, the Blairsville, Georgia, mother was cleared.

There are many more similar cases than could reasonably be mentioned here, but the trend is clear: at a time when risks to kids are historically low, the legal consequences have dramatically increased, punishing parents for behavior that would have been considered commonplace for kids growing up in the 1960s or 1970s. A recent study published by the Society for Research in Child Development traces the evolution of neglect laws in the United States, passed with the laudable goal of keeping children safe. The authors examine how such laws have negatively affected the ability for children to become resilient and prepared face the inevitable challenges that come with navigating life as an independent adult by effectively reducing the opportunities for independent activity—a necessary component of child development.

For most parents in the United States, even if they want to allow their kids some independence, there are legal risks that they must consider in addition to an unfriendly parenting culture. But while any cultural shift would take place over time as more parents recognize the benefits of reasonable childhood independence and free play, there are policy solutions to make sure that parents do not face legal consequences for trusting their children.

Reasonable Childhood Independence Laws and Shifting the Culture

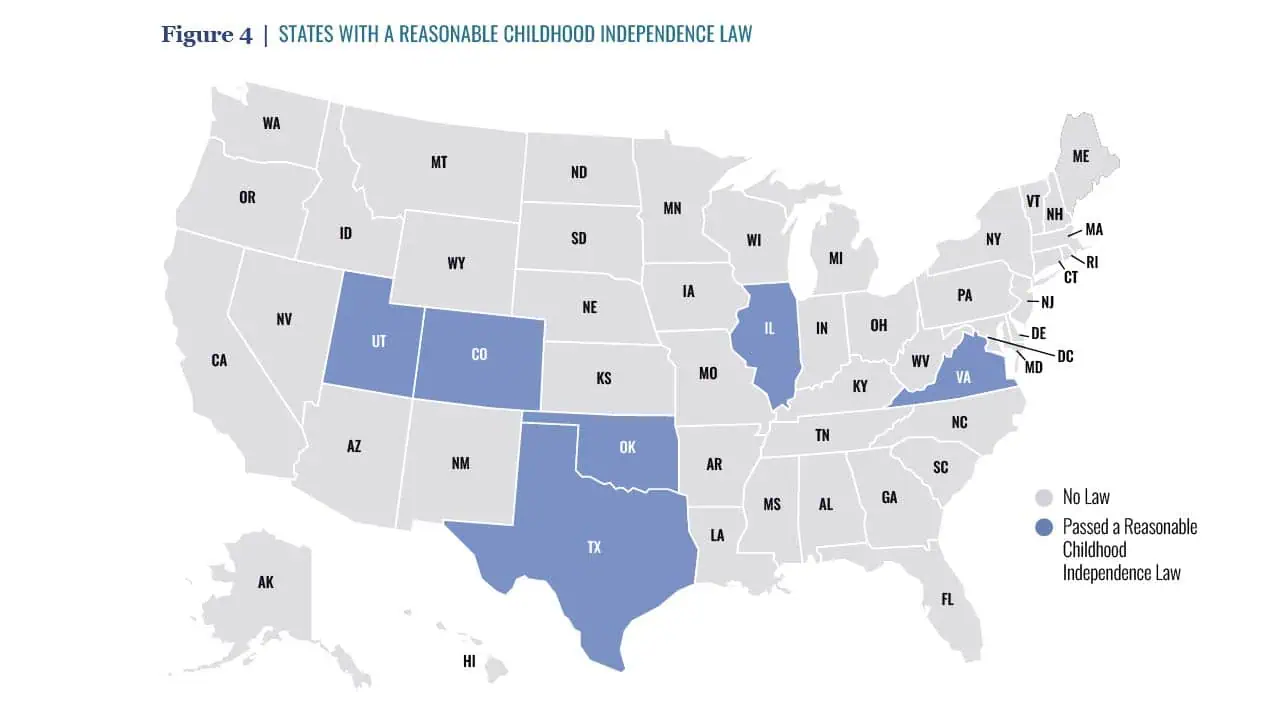

Beginning with its adoption in Utah in 2018, Skenazy and Let Grow have pioneered state legislation to legalize parents giving children a reasonable amount of childhood independence. Appropriately dubbed “Reasonable Childhood Independence” laws, these measures modify state law to ensure that parents are protected from charges of negligence or neglect for allowing their kids to engage in appropriate unsupervised activities. Following Utah’s adoption in 2018, Oklahoma (2021), Texas (2021), Colorado (2022), Illinois (2023), and Virginia (2023) have each also passed a Reasonable Childhood Independence Law. Also in 2023, while stopping short of adopting a comprehensive protection for parents, Connecticut took some significant steps to mitigate the most punitive aspects of its laws which previously precluded any child under the age of twelve from being unsupervised in a public place.

Although there are several different versions, the essential change these laws make is to clarify that parents cannot be legally penalized for letting their kids engage in some unsupervised activities. Reasonable Childhood Independence Laws do not repeal the laws governing neglect or negligence. Rather, they refine the meaning of these statutes, which are often vague in nature and leave far too much discretion for authorities to restrict independence. Typically, such laws prohibit neglect charges from being filed for a single incident when a child is unsupervised for a reasonable period of time, while preserving the ability for such instances to be included in a broader investigation if necessary. Several of the laws even list specific activities for which a parent cannot be charged with neglect for allowing their children to do (unless they are blatantly disregarding an obvious danger), including specifically such activities as walking to or from school, playing outside, or spending a reasonable amount of time alone at home as protected under the law.

Another benefit of these laws is the fact that they have consistently been met with a rare display of bipartisanship. Protecting parents who want to give their children opportunities to play independently or build important life skills isn’t a partisan issue. Indeed, the current tally on the laws’ is three Republican-controlled states have passed the law and three Democrat- or mixed-controlled states have passed the law (with one more making significant improvements to its neglect laws). Within these states, passage has often been unanimous. While the momentum is encouraging, there are still more than 40 states that have yet to adopt a law protecting parents. For those states, Let Grow’s Legislative Toolkit may prove to be a helpful resource as policymakers and parents consider how best to craft legal changes to benefit children and protect parents.

While it’s true that parents and kids deserve these protections in their own right, these laws are likely the single most effective, achievable, and bipartisan policy to help ensure kids have the opportunity to build the skills necessary to succeed in the future. Policymakers should recognize such laws for what they are: an essential piece of building tomorrow’s skilled workforce.

Ensuring legal protection is an important and necessary step in shifting the culture toward one that is accepting of free play and reasonable childhood independence, but it is by no means the whole story. In addition to policymakers, parents, educators, and therapists must be a part of the solution as well. For parents, Let Grow offers Independence Kits that give parents ideas for how to allow their children increasing levels of responsibility and independence. Let Grow also has a similar kit for teachers called “The Let Grow Project,” a homework assignment that gets kids K-8th grade doing new things on their own. The implementation guide is free and they even offer ideas and guidelines for how to set up a mixed-age, no-devices “Let Grow Play Club” before or after school. An adult supervises the free play like a lifeguard, but they don’t organize the games or solve the spats, so kids have some space and opportunity to interact independently. The play club implementation guide is free as well.

For clinical therapists working with parents to give kids doses of independence, Dr. Camilo Ortize recommends equipping kids engaging in free or independent play with Let Grow’s “Kid Licenses.” These are little cards that kids can show other potentially concerned adults that let them know that these kids are doing okay and that they have permission to be doing what they’re doing. They include a brief explanation, the parents’ name(s), phone number(s), and invites adults to call and check.

These are useful tools and hopeful trends, but as is the case with many issues, positive change comes down to individual action. The law can allow free play and reasonable independence, and there can be resources available for how to go about giving kids the room to grow, but ultimately it will be up to parents to make the decision to allow their kids the opportunity to learn and grow a bit more independently.

Conclusion

We are living at a time of unprecedented technological change, and all indications point toward an even more disruptive future. Artificial Intelligence is poised to revolutionize the nature of work, just as automation and technological changes have done over the past several decades. The economy has firmly shifted from being primarily goods-based to primarily service-based, and with that change, the skills that workers require to be successful have also shifted. Soft skills (or non-cognitive, character, or socio-emotional skills) have become essential for workers seeking to succeed in the workplace and effectively navigate their careers and lives. While we do not know with certainty, there is good reason to believe that those skills are likely to become even more important as new technologies make their way into industries and businesses across the globe.

Building those essential skills is an important prerequisite to ensuring that the economy can continue to grow, businesses are able to recruit effective employees, and most importantly, individuals are able to succeed. These skills are developed early in life and build on one another as a person gets older. The evidence is clear that soft skills begin in the home at the family level but also that social environment and interactions with peers are important factors as well. As policymakers consider how best to ensure kids have the opportunity to climb the income ladder, prioritizing soft skill development by strengthening families and enabling free and independent play are the areas warranting the most significant policy attention.

Not only will soft skills built through strong families and independent free play yield beneficial results for competition in the labor market, but such skills are also engines of resiliency and robust mental health—a benefit that shouldn’t be overlooked at a time when poor mental health trends, particularly among young people, are at an all-time high. While the ultimate responsibility for the development of soft skills in the next generation rests with parents, there are several public policies that would make the legal environment much more conducive for soft skill development—starting with the adoption of Reasonable Childhood Independence laws that protect parents from facing legal consequences for simply allowing their children to engage in some independent activities.

Providing their children with the opportunity to develop soft skills is the duty of every parent, but it’s up to policymakers to lift the barriers that stand in their way. Whether it’s by allowing kids to exercise some independence, have some time to play with friends without constant adult supervision, or even just removing the policies built into social safety net programs that discourage marriage, public policy should never impede the development of soft skills. As new technologies upend traditional employment, soft skills are the foundation on which new trends, industries, and enterprises will be built.

Ben Wilterdink is the former Director of Programs at the Archbridge Institute. Follow him @bgwilterdink.