Her Westchester County neighborhood was the home of Vanderbilts, Morgans, and Astors. Jay Gould and John D. Rockefeller had assembled estates nearby. Sitting high above the Hudson River in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, “Villa Lewaro” had views of the river and the Palisades on the opposite shore. Her mansion’s interiors were as sumptuous as the views — including ivory-enameled mahogany, hand-woven Aubusson carpets, a Cartier sculpture, and a large Estey player organ. Most elegant of all was Madam C. J. Walker herself, bedecked in diamonds from Tiffany’s, as she welcomed her guests in 1918.

Madam Walker’s accomplishments were staggering. She was almost 40 when she began to develop her business and only lived another 14 years. Yet in that period she trained over 40,000 agents, created great jobs for many more, helped millions with her hair care products and methods, visited every corner of America, donated to a multitude of causes, and played a strong leadership role in the African American community. The fact she was worth $600,000 when she died (almost $10 million in 2017 dollars), one of the wealthiest black women in the world — if not the wealthiest — was perhaps the least important of her achievements.

Madam Walker was not born to such status. She was born to slaves — her father valued at $700 and her mother at $600 on their owners’ books, alongside horses, corn, oxen, and farm implements. She, her parents, and five siblings shared a one-room sharecropper’s cabin. Soon she was an orphan and a single mother. But she did not let this humble beginning hold her back. Madam Walker was one of the most remarkable self-made women — or person of any gender — in American history. This is her story.

“I got my start by giving myself a start.”

Up from the Cotton Fields

On December 23, 1867, Sarah Breedlove — later to become Madam Walker — was born to Owen and Minerva Breedlove, the fifth of six children of cotton-picking freed slaves. The plantation they lived on was in Delta, Louisiana, three miles south of and across the river from Vicksburg, Mississippi. Delta consisted of less than 60 whites and hundreds of former slaves, still working the plantations. Sarah was born free, but her five older siblings were born as slaves, the property of others.

In 1867, Congress overrode President Andrew Johnson’s veto to pass the Reconstruction Act, which enfranchised 700,000 black adult men across the South. The federal government divided the South into five military districts to protect their rights. Federal troops were stationed at nearby Vicksburg, offering more protection to Delta than blacks were afforded in other parts of Louisiana.

In September of that year, 39-year-old Owen Breedlove was able to cast the first vote in his lifetime, for delegates to a Louisiana state convention to rewrite state laws. Half the delegates were black, half were white. All but two were Republicans. The New Orleans Times called the convention the “Congo Convention.” President Johnson accused the Republicans of trying to “Africanize half of our country” and said the African Americans were “utterly so ignorant of public affairs that their voting can consist of nothing more than carrying a ballot to the place where they are directed to deposit it.” And yet the black delegates were generally at least as well educated as Johnson was, though most of their voters were illiterate, having been kept so by their owners.

The convention delegates aimed to secure voting rights for adult black males, offer public education to the freed slaves, and outlaw segregation on trains and in public places. The unseated Democrats were not happy and committed to prevent change. They demanded a “government of white people” and formed the Knights of the White Camellia (later the White League) to “fight for their rights”. During 1868, there were a thousand murders of the blacks and Republicans. No whites ever were arrested for such crimes. By November 1868, voters in most Louisiana parishes had been frightened into not voting or voting for the Democrats, who won handily.

This world, and a world of picking cotton in the hot sun alongside her parents, was the world young Sarah Breedlove was born into. Like other little black girls, her hair was pulled hard, “cruelly braided,” and covered in a head wrap. In 1874, when she was old enough to enter the first grade, public schools in Louisiana were closed when the state legislature refused to fund them. Schools set up for African Americans were burned, teachers intimidated and even killed. There would be no place for educated blacks. In her lifetime, Sarah Breedlove was to receive only three months of formal education. Everything else she learned was acquired through her own efforts or was taught to her by friends.

When Sarah was five, her mother died. At seven, her father followed. She moved in with her sister and abusive brother-in-law. With life itself threatened in Louisiana — lynchings of blacks were common — and the unpredictability of the cotton crop, the three moved to Vicksburg in about 1878. There, at the age of 11, Sarah found work as a laundress for wealthier white people. At 14, unhappy with life at home, she ran off with and married Moses McWilliams, “to get a home of my own.” In 1885, her sole child, daughter Lelia, was born. Within six years of their marriage, Moses was also dead, rumored to have been the victim of one of 1888’s 95 lynchings.

“If I have accomplished anything in life it is because I have been willing to work hard.”

New Friends in the Big City

With their lives endangered, many African Americans left the South and headed north in the hopes of a freer society and better-paying jobs in the cities. Upriver from Vicksburg was one of the nation’s biggest cities, St. Louis. In 1889, Sarah and Lelia joined Sarah’s older brothers, who had attained relative prosperity as barbers in St. Louis. Over the next few years, the two women moved constantly from rooming house to tenement to rooming house. Sarah found work as a laundress, like other black women who had few options outside of domestic work in white households. (In 1900, 65% of American washerwomen were black.)

Nevertheless, she was committed to educating her daughter. Lelia spent a part of each week at an orphanage which had offered to help her along. When she turned four, her mother put her into elementary school.

The big city of St. Louis was eye-opening for Sarah. Unlike Louisiana, the black community included doctors, teachers, lawyers, and other professionals. She became heavily involved in this community, including the St. Paul AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church. She met many interesting and thoughtful people of both races, and maintained these friendships throughout her life. She joined the Court of Calanthe, the women’s auxiliary of the black Knights of Pythias “secret society.” She became friends with the publishers of black newspapers.

In 1894, Sarah married John Davis, possibly believing Lelia needed a father. This marriage, too, did not last — within nine years, Davis had run off with another woman.

While St. Louis offered new cultural and educational opportunities, it also had the temptations and evils of a big city. The neighborhood where Sarah lived was known as the “Bad Lands” because of the violence, gambling, taverns, and prostitution. In the fall of 1902, Sarah paid $7.85 for the first month’s room and board for Lelia to attend high school and college courses at Knoxville College in Tennessee.

Despite her lowly working status and low income, Sarah did everything in her power to help other new arrivals from the plantation South, including providing money and gifts. Thus began her lifelong dedication to helping others through philanthropy.

Around 1903, Sarah started seeing Charles Joseph Walker, a dapper, fast-talking, smartly dressed promoter and huckster. Possibly from his influence, she began to pay more attention to her appearance. But her hair was breaking and falling off. She later said, “I tried everything mentioned to me without any result. I was on the verge of becoming bald.” Her problems were shared by many African-American women of her era. Infrequent washing — often in dirty water — combined with dandruff and psoriasis resulted in clogged pores from which hair would not grow. So began her interest in hair care and solutions. In 1903, Sarah became a sales agent for the hair care products of Annie Pope-Turnbo, with whom she would later compete.

“I had to make my own living and my own opportunity. But I made it! Don’t sit down and wait for opportunities to come. Get up and make them.”

“I Had a Dream”

In 1904, the St. Louis World’s Fair brought most of the major African-American thinkers to the city, and Sarah attended their talks. This was her first exposure to the most prominent black American, Tuskegee Institute Founder Booker T. Washington, and to his sometimes-adversary, W. E. B. Du Bois, who often took a more radical approach to improving the lot of black Americans.

Ever-seeking new opportunities, and possibly to get away from her past with John Davis, in the summer of 1905 Sarah again moved, this time to live with her sister-in-law in the clean air and economic possibilities of a booming mining town — Denver, Colorado. Here she was not surrounded with the old white family money of St. Louis but with the self-made entrepreneurs of gold and commerce. She arrived with $1.50 in her pocket, and got a job as a cook in a boarding house for $30 a month.

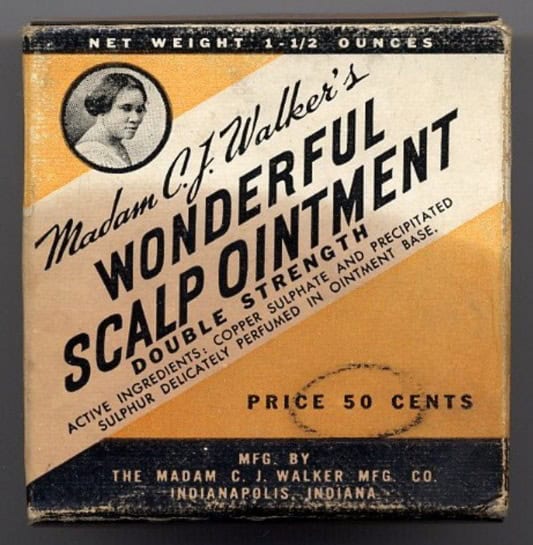

Then, according to her, “One night I had a dream, and in that dream a big black man appeared to me and told me what to mix for my hair.” In November of 1905, she rented a small attic, her first laboratory. She was soon spending two days a week doing washing, and five days a week giving hair treatments with her new products. She claimed the dream included ingredients from Africa, which gave them extra appeal, and may have included coconut oil. The other key parts of the recipe were petrolatum, beeswax, copper sulfate and precipitated sulfur, and violet extract perfume to cover the sulfur’s odor, with a separate treatment of the disinfectant carbolic acid. And all this worked. Throughout her life, she claimed that she could grow hair from any scalp where the roots were not dead.

Throughout the evolution of her business, there was substantial controversy over hair care products for African-American women. Some blacks decried them as “hair straighteners” in mimicry of white women’s hair — but Sarah consistently denied that was her goal, and took offense at the claims. Her product “grew hair.” The early cosmetics industry, like most remedies of the era, also contained many quacks and hucksters, with no restrictions on the often-dangerous ingredients. It was a tough market.

C. J. Walker, who was skeptical of her business, nevertheless joined Sarah in Denver and helped her promote her product using his skills as a natural salesman. In January 1906, at the age of 38, Sarah married C. J. That spring, she began to go by the presumably more prestigious “Mrs. C. J. Walker,” but by summer had adopted the moniker “Madam C. J. Walker,” using a term long common among hairdressers. That name stuck and soon enough became famous across the nation.

The newly christened Madam C. J. Walker continued to promote her product, “Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower.” She printed up her first business cards and was soon advertising in black newspapers. She got to know more editors and publishers, and more influential people, a network that expanded throughout her life.

With her new product in hand and her advertising working, Madam Walker began her peripatetic life of traveling to every town and city she could visit, talking about and selling her hair care products and methods. She visited every nook and cranny of Colorado. For the rest of her life, she was almost continually on the move.

In 1907, she took in $3,652, nearly triple what she had made in the prior year. This income was ten times what she had earned as a laundress or cook. The $300 per month was more than all but the highest paid corporate executives in America earned. Most black women made $8 to $20 a month; white male factory workers $40 to $60.

Then Madam Walker began an 18-month tour of all the Southern states, where she knew most of her 3 million potential customers lived. She lectured, she trained, she sought agents to sell her products and thereby make a better living for themselves. Great numbers of customers bought her cures and hundreds of sales agents signed up everywhere she traveled.

By the winter of 1907, she decided again to move — this time to a rail center so she could more easily ship her product to the markets she was serving. She landed in Pittsburgh, then a booming center of steel and other industries. She opened a Walker Hair Parlor there and trained dozens of agents. She traveled throughout the Northeast and New England.

Revenues in 1908 reached $6,672; 1909 hit $8,782. But her upward curve had just begun.

In 1909, Lelia married John Robinson. But she was just as unlucky in love as her mother, and he disappeared within a year. Nevertheless, Lelia had some of her mother’s aptitudes and soon engaged in the business, taking over the Pittsburgh training school and parlor her mother had established.

In 1910, Madam Walker again decided to relocate. This time she picked another transportation hub, and a cleaner city than Pittsburgh: Indianapolis. While she would move herself again, the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company would stay anchored in Indianapolis for the rest of its existence. There she built up a large network of friends and built a beautiful home, laboratory, and factory, hiring local women to mix the product. All orders henceforth were sent to Indianapolis.

Also in 1910, she wrote to the famous Booker T. Washington, asking him to invest in her newly formed company. He answered with a polite “no.”

In Indianapolis, she hired one of the city’s first African-American lawyers, Freeman B. Ransom. “FB” was to become a lifelong friend and advisor, overseeing her business and financial interests up to and beyond her death. Madam Walker was the godmother to his children. At least she found a good man; for by 1912, C. J. Walker had run off with a girlfriend and Madam Walker divorced him but kept his last name. C. J. was her third and last husband.

The Community Activist

In the summer of 1910, Madam Walker expanded her network by attending as many black conventions and conferences as she could, including the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), in which she became very active. Over the course of her life, there were almost no major black organizations or movements that she was not a part of. She joined, and she gave. She continued to help anyone in need whom she thought deserved the help and would work to improve themselves. Her speeches not only sold hair care products, but they encouraged women (and men) to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, just as she had done. That fall, she did another eight-state Southern tour. Sales for the year totaled $10,989.

As hard as she worked and as famous as she became, she was still a black person. When she laid down her dime to attend a movie in Indianapolis, she was told it was 25 cents for colored folk. She never became violent or lashed out but worked hard every day to fight such prejudice.

In 1911, Sears, Roebuck’s president and controlling stockholder, Julius Rosenwald, offered any American city $25,000 if its citizens would raise $75,000 on their own to build a YMCA in their black community. (Rosenwald also paid for thousands of schools for blacks in the South.) Indianapolis was among the first cities to take up his generous offer. Soon the leaders of the white YMCA joined in the effort, and separate campaigns among whites and blacks competed to reach their goals. Indianapolis’ white business leaders joined the effort: Indianapolis Motor Speedway founder Carl Fisher led the way with a $10,000 donation. Among African Americans, Madam Walker’s donation of $1,000 was the largest. With heavy newspaper coverage, the campaign exceeded its $100,000 goal, including donations totaling $20,000 from more than 1,500 blacks.

In 1912, Madam Walker again wrote Booker T. Washington, asking for the right to speak at his upcoming Negro Famers conference. Again, he said no. She wrote him again, and this time was allotted ten minutes of speaking time on a minor platform. She took every opportunity, and she always persisted. Nothing could stop her.

That same year, Booker T. Washington’s 3,000-member National Negro Business League (NNBL) held its annual meeting in Chicago. This seemed a natural place for the nation’s most prominent black woman entrepreneur to speak. Washington gave the floor to some of her hair care competitors, but when a newspaper editor stood up to introduce Madam Walker, Washington curtly dismissed him and would not let Madam speak. Despite these numerous rebuffs, Madam Walker was not to be ignored. On the final day of the convention, she stood up and said, “I am a woman that came from the cotton fields of the South. I was promoted from there to the wash-tub. Then I was promoted to the cook’s kitchen, and from there I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations . . . I know how to grow hair as well as I know how to grow cotton.” Newspapers called her comments one of the big hits of the convention, praising her “striking personality.”

By 1913, Madam Walker’s company was doing $3,000 a month in sales. She bought a limited-edition Cole automobile, with a powerful 40-horsepower six-cylinder engine, and had a chauffeur to drive it. She hosted many visitors to her beautiful Indianapolis home and her factory, including at last Booker T. Washington. By the time she and her friends were chauffeured to New York and then to Philadelphia for the next NNBL annual meeting, Washington had finally decided to give her time to speak.

Everywhere she traveled, Madam Walker sought to inspire others with her story, to fight prejudice, and to promote self-reliance. And always — always — to sell hair products, treat others’ hair, establish parlors and training centers, and recruit new agents. She told her story with a glass slide show that impressed hundreds of audiences in all the places large and small that she visited.

“I am not satisfied in making money for myself. I endeavor to provide employment for hundreds of the women of my race.”

Growing Hair and Growing People

In late 1913, seeking ever-expanding markets, she visited Jamaica, Haiti, Costa Rica, Panama, and Cuba.

Continuing to develop her love of “the finer things,” in 1914 she gave her daughter, Lelia, who had moved to New York City the year before, a Cadillac. Lelia urged her mother to move to New York, with its culture and excitement, and Madam enjoyed her visits. Finally, in 1916, Madam approved the purchase of a town house in Harlem. Over $15,000 was spent on the building and its lavish interiors before Madam moved there (though the factory and F. B. Ransom stayed in Indianapolis).

Harlem was originally a rural retreat for wealthy white people from far down Manhattan Island. But with the growth of the city and the coming of elevated railway lines, it began to attract African Americans of all income levels. Poets, musicians, writers, and other creative types were drawn to this hub, often viewed as the most advanced community of black people anywhere in the world.

Madam Walker’s residence was upstairs above one of the poshest hair parlors in New York City, with marble and parquet, rivaling the parlors of Elizabeth Arden and Helena Rubinstein on Fifth Avenue. She hired Vertner Tandy, one of the first black architects licensed by the state of New York, to design it. Her upstairs residence contained a gold Victrola phonograph, a fine piano, an intricately carved fireplace, and English wall tapestries. The house soon became a center of social activity and meetings about the plight of black Americans.

But Madam continued her journeys. She trained 10,000 agents, who could earn $15 to $40 a week, four to ten times what they could earn in domestic work. In Chicago, Rosenwald’s Sears and competitor Montgomery Ward hired 1,500 black women as mail order clerks, but other white-collar and high-paying jobs were few and far between for black women. In 1916, Madam Walker’s sales reached a staggering $100,000.

That year, she organized her 200 New York area agents into the first chapter of the Madam C. J. Walker Benevolent Association, urging her agents to help others who were struggling and to donate to good causes. She always led by example.

Madam Walker decided to pick her very best agents, those with leadership potential, and elevate them to “treat, teach, and organize.” She paid them $125 per month, $1,500 per year. At this time, executive-level federal employees made $1,200 per year and white school teachers earned $337 per year. At the same time, back in Indianapolis, she made sure the factory workers were paid as much or more than the office workers, knowing how hard their work was. She said that everyone seemed to be looking for an easy job. She knew what she had experienced, and knew that only the driven, ambitious workers would go on to great achievements.

Perhaps because of her nonstop work, she had hypertension. And in 1917, she was diagnosed with nephritis, an inflammation of the kidneys. Doctors ordered her to Dr. John Harvey Kellogg’s Sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan, but she did not stay long, ever-eager to return to her mission.

“Perseverance is my motto.”

Fighting for Her Race

At the same time, “race riots” took place across the country, with some of the worst in Springfield and East St. Louis, Illinois, and in Waco, Texas. Thousands of blacks were lynched, some were burned alive, others were kicked down the street until dead. In East St. Louis, 6,000 blacks were burned out of their homes in a struggle with white Union factory workers. Madam supported a silent protest march of 20,000 in New York City.

She became more and more active and outspoken, joining and funding the NAACP and the NACW, and always speaking, telling her inspiring story. In August of 1917, she held the first national meeting of Walker agents in Philadelphia, drawing 200 delegates from nearly every state.

The groups she joined began sending letters to President Woodrow Wilson and his cabinet. Democrat Wilson was the first president from the South elected since the Civil War. He had instituted racial segregation of black civil servants in previously integrated federal buildings, barring them from government cafeterias. In his first term in office, black federal appointees dropped from 31 to eight. The letters of the African-American organizations went unanswered or received polite “no’s.”

Then came World War I. At first, the Red Cross would not even allow black volunteers but later relented, and Lelia became one of them. Life was tough for the many black volunteers, even though a bigger share of blacks of military age enlisted than the share of whites. First Lieutenant Charles Tribbett, a black electrical engineer and a Yale graduate, was arrested and forced from a train en route to training camp, because he had violated Oklahoma state law by daring to occupy a Pullman car.

New York’s 369th “Hellfighters” were relegated to a French command. They were named the Hellfighters because the Germans called them “blutlustige schwarze manner” — “bloodthirsty black men.” They endured 191 days of uninterrupted enemy fire. The French were so impressed that they let the 369th lead the way into Germany after the Armistice was signed. The French government awarded them their highest honor, the Croix de Guerre. New York City welcomed them back with an enormous parade. Even the richest white men stood in their honor and saluted and waved at them.

In 1917, Madam Walker began building her mansion in Irvington-on-Hudson. Madam was never ashamed — never ashamed of her humble origins or of the wealth she had amassed through hard work. She loved beautiful things and surrounded herself with them. Her friend the famous tenor Enrico Caruso suggested the name Villa Lewaro, based on her daughter’s name LEila WAlker RObinson.

Madam Walker became more politically active than ever. In those days, as now, there was tension in the African-American community between the more conservative “Bookerites” and the more aggressive (and occasionally leftist) leaders like A. Philip Randolph (who was supported by his wife, a Walker agent). Madam Walker invited all of them to her home and tried to make peace, as she was only interested in “the betterment of the race.”

As the Paris Peace Conference to settle the division of German properties approached, there began a movement in the African-American community to have “a seat at the table.” In addition to fighting global prejudice against people of color, they wanted the former German colonies in Africa turned over to black leaders, whether from Africa or from the world African-American community. Madam Walker and many others applied for passports to France. But all were denied by the Wilson administration, often because their names were on lists of “subversives,” having associated with “known socialists.”

Rejected in her international efforts, Madam Walker and other black leaders turned their efforts to an anti-lynching campaign. President Wilson still refused to make any public statements on the issue, desiring to not get involved in “the race issue.” Belatedly, he made some modest public comments against racial prejudice.

The Final Chapter

The Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company had sales of $275,938 in 1918.

Madam Walker became ever sicker from her kidney disease, but refused to slow down very much. She said, “My desire now is to more than ever for my race.” But on Sunday morning, May 25, 1919, just after her grandfather clock chimed seven, Madam C. J. Walker died at the age of 51.

That year sales almost doubled to $486,762, and went on to $595,353 in 1920, carried forward by the momentum — and agents — that Madam Walker had created. Few cosmetics companies in the world were as large.

Her beloved daughter, Lelia, went on to become a star of the “Harlem Renaissance” of the 1920s, but died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 46 in 1931.

The Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company lingered on in Indianapolis until the 1980s. The old factory and home are now the Madam Walker Theatre Center, home to performing arts and a small museum. Both those buildings and Villa Lewaro are National Historic Landmarks.

The ultimate legacy of this incredibly strong woman to men and women of all colors is her audacity, her bravery, her persistence, and her generosity. Few have overcome so much to reach heights so great.

The preceding story is based on the outstanding biography of Madam Walker On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, by her great-great-granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles and published in 2001. It is well worth reading if you are interested in learning more about Madam Walker, her multitude of acquaintances, and events and life in this era.