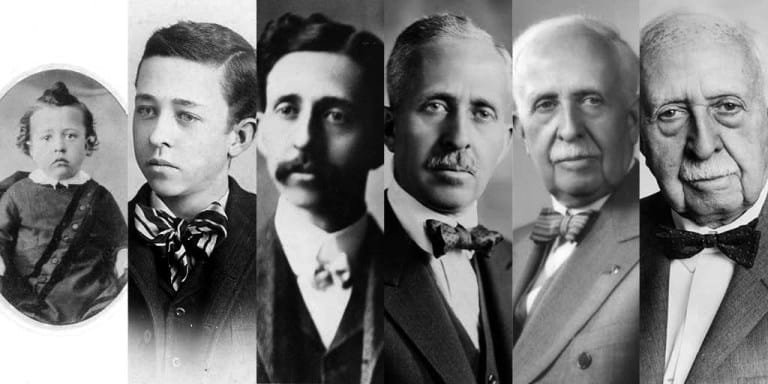

From inauspicious beginnings rose one of the great entrepreneurs in American history, a man with unusual dedication and exceptionally high ideals. James Cash Penney, Jr., was born September 16, 1875, near Hamilton, Missouri, to the Reverend James C. Penney and his wife, Fanny. The boy was one of twelve children, only six of whom survived to adulthood. His father was a less-than-prosperous Baptist preacher who also farmed. A man of strong Christian beliefs and upright morals, Reverend Penney later repeatedly ran for office on Populist tickets: he never won. The younger J. C. Penney survived being widowed twice and losing almost all his wealth in the Great Depression, but continued leading, writing, teaching, and preaching until his death at the age of ninety-five. Above all else, at every stage of life he shared everything he had. His name lives on on over eight hundred stores across the United States

EARLY LESSONS

When he was between eight and ten years old, Reverend Penney told young “Jim” that he needed to earn money to contribute to the family’s limited coffers. Jim then profitably raised and sold hogs. But when neighbors complained about the squealing noise, his father made him sell the pigs well before they were fattened for market. Jim wasn’t happy, but went along with his father’s wishes. At fifteen, he started working Saturdays in a local store and took a liking to storekeeping. In high school, he was a mediocre student but an outstanding orator, delivering uplifting messages about patriotism, Christianity, and the merits of hard work to his fellow students.

Reverend Penney worked hard to instill ethics in his son. In one storekeeping job, Jim discovered the owner substituting cheap coffee into the container of a higher priced product: his father demanded that he quit. Later, the entrepreneurial young man sold watermelons outside the gates of the local fair. But his father pointed out that those selling watermelons inside the fairgrounds had paid a concession fee, and insisted Jim stop competing unfairly.

At nineteen, Jim took a job at the J. M. Hale dry goods store for $25—for eleven months work—just $2.27 per month. That spring, his father died; among his last words were, “Jim will make it. I like the way he has started out.” This inspired Jim for the rest of his life. He worked hard, learning the inventory and doing whatever tasks needed to be done, no matter how humbling. The next year, Jim earned $200, and $300 in his third year—a luxurious $25 per month.

When he was twenty-one, the family doctor noted that Jim was wearing down and risked getting the dreaded “consumption” (tuberculosis). He suggested Jim move west where the air was clearer and drier. With letters of recommendation in hand, the young man headed west toward the Rockies in the summer of 1897. He arrived in Denver, then booming from mining on one side and farming on the other. In his second job there, as a dry goods clerk, he discovered the merchant had a dual pricing system: high prices for those who could afford them, half price for those who could not. Jim could not tolerate the unfair practice and immediately quit.

He increasingly realized that he wanted to own his own store. Writing home for his $300 in savings, he bought a butcher shop in nearby Longmont. The main customer was a local hotel. The man who sold him the butcher shop said he could hold onto this key customer as long as he bought the hotel manager a bottle of whiskey each week. For a while, Jim did this, then he realized his father would have never put up with the bribery. He cut off the whiskey, lost the customer, and the butcher shop failed, Jim losing all his savings in the process. In a land far from home, he was on the street, alone.

“A man who cannot make a mistake cannot make anything.”

THE BIG CHANCE

Not far from the butcher shop was the busy Golden Rule Store, owned by fellow Missourians Tom and Alice Callahan. The couple had been inspired by Tom’s mother, Celia, who operated a very successful low-price store in Chillicothe, Illinois, after moving from Missouri. The name “Golden Rule” was suggested by Alice’s father. By selling dry goods, notions, shoes, and clothing at fair prices, the Callahan’s Golden Rule Store in Longmont had prospered. The store’s net worth had risen from $500 to $50,000 in the ten years since its 1889 founding. As a result of the store’s success, the Callahans lived in one of the nicest homes in town.

Callahan advertised constantly, and included pictures of items in his ads, a rarity then. New products were advertised each week. To keep expenses (and therefore prices) low, they did not deliver and did not offer credit. Despite miners often being paid in scrip that could be spent at mining company stores, The Golden Rule only sold for cash, rare for the time. Inventory sold faster and was turned over more frequently than in most similar stores. Perhaps most importantly, there were several Golden Rule Stores around Colorado owned by various partners (including relatives), and they pooled their purchases on the semi-annual buying trips to Kansas City, St. Louis, and New York. Golden Rule prices were often 25–50% below those of other merchants, but the stores always offered good, dependable quality merchandise and the latest fashions.

Despite Callahan’s hesitation at “hiring a butcher,” Jim Penney got hired at the Longmont Golden Rule as a part-time sales clerk when a senior clerk was ill. He spent long hours again doing “whatever it took.” He was endlessly curious and an outstanding salesman. When the senior clerk came back to work, Tom Callahan kept Jim on. Soon enough, Callahan asked Jim to move to Evanston, Wyoming, where Callahan and partner William Johnson operated another Golden Rule Store. Callahan and Johnson had previously promoted store managers to partners, and implied to Jim that the same might happen to him if he performed. Jim jumped at the chance, without even asking how much he would be paid. The possibility of opportunity lit his fires.

In March of 1899, Jim Penney arrived in Evanston, population 2,000, and began as a junior salesman, at a salary of $50 per month. He folded the inventory. He dusted the floor between customers—up to ten or eleven times a day. He was soon promoted to “first man”—the top sales clerk. He finally felt secure enough to ask his longtime girlfriend, Berta Hess, to marry him. She had survived a failed marriage, but Jim married the divorcee he loved even knowing others might not approve. The couple attended church, and had their first child, a boy, in 1901.

Jim was relentless. He often went home late, could not sleep, and thought about the store through the night, until he got up the next morning to dash back to the store. He was deeply loyal to Callahan and Johnson, from whom he learned so much. He turned down higher offers from competitors. In the fall of 1901, the two partners told Jim they wanted to open a new store in huge Ogden, Utah (population 20,000). They offered him a one-third partnership in the new store if he would run it, and further said they’d loan him the money. But Jim deferred, saying Ogden was too big, that he preferred smaller towns where he could know all his customers and their needs. In truth, he did not want to go into as much debt to the senior partners as would have been required to finance a big store in Ogden.

After much debate, Jim convinced them to open the next store, his store, in Kemmerer, Wyoming, in the heart of a growing coal district. The partners were wary, as other ambitious men had failed to make stores work in the town of nine hundred people. Jim put up his entire savings of $500. Callahan and Johnson offered to loan him the balance of $1,500 in order to buy his one-third ($2,000) share of the $6,000 investment required, at 8% interest. But he wrote a hometown Missouri bank and got the same loan at 6%. He said he saved $30 and it only cost him a postage stamp. In the partnership agreement, Jim Penney received a salary but also got one-third of the store’s profits, if any.

Jim’s “big chance” was a store 25-feet wide and 45-feet deep. First day’s sales were a gratifying $466.59. The young couple lived above the store, using shoe boxes for chairs and packing cases for tables. Water was drawn from a nearby well and hauled up to their rooms by bucket and rope. Berta waited on customers while their baby boy slept under the counter. The store opened at 7 a.m. except Sundays, when they opened “late” at 8 a.m. They closed each day just before midnight. The Penneys learned the names of all their customers, even if they only came to town once or twice a year. They remembered their sizes and preferences.

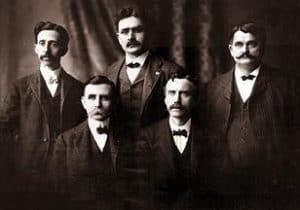

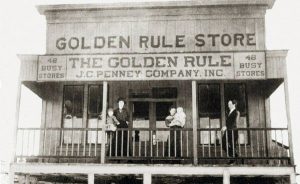

Penney on the left, next to Tom Callahan,

with William Johnson on the far right.

In the first year (1902), the store did almost $29,000 in sales, and made a profit of $8,500. Penney had turned his inventory over almost four times, an impressive number. The senior partners then offered him a one-third interest in the nearby Rock Springs store if he would oversee it as well. By 1903 Jim was also participating in buying trips, introduced by his partners to their many Eastern suppliers. Kemmerer boomed to a population of 2,000. Kemmerer profits rose to $9,800 and then $11,250 in the next two years. Jim’s $3,750 one-third share of the 1904 $11,250 profit is equivalent to about $102,000 today, not including his manager’s salary.

At the age of twenty-nine, J. C. Penney was well on to his way to becoming a wealthy man. He and Berta named their second son Johnson Callahan Penney in honor of his revered mentors and partners. But his ambition was not satisfied.

EXPANDING HORIZONS

Johnson, Callahan, and Penney opened a store in another mining town, Cumberland, Wyoming, around the first of 1905. In 1907, looking for a man (they were all men back in those days) to work in the Cumberland store, Penney had an interesting and extensive correspondence with Earl Sams from Kansas. Sams had been recommended by a Denver employment agency. Penney, who had passed on an applicant who would not work Sundays, wrote Sams to insure nothing was misunderstood, “[Our man] must be a hustler, not afraid to work. We open at seven, and never get closed till nine or ten o’clock, work half day Sunday. We have a good future for a man who is capable and not afraid of work.”

When Sams arrived in town for a final interview, some locals told him Penney was an honest man but a hard man to work for. Sams was offered a store manager’s job at a competitor, compared to the sales clerk job that Penney offered him. The pay was $100 a month versus the $50 that Penney offered. But Sams decided to go with Jim Penney. When he later arrived on a late train with his family, he had a small terrier with him, and Penney worried that it would distract from his work. But Earl Sams not only earned Jim’s confidence, but later went on to follow Penney as president of the company and head of day-to-day operations for almost thirty years.

An early store.

J. C. Penney, as he was now more often called than Jim, had no limits on his ambitions. He could foresee the day when his Golden Rule Stores, still co-operating with a larger buying syndicate of similarly named stores throughout the West, would number twenty-five, or even fifty. When presented with the opportunity, he bought out his aging senior partners. But he also found and developed new, younger partners, always loaning them enough to own one-third of their own stores if needed in order to make sure they had an investment in their stores and shared in any success achieved.

The following years’ store openings indicate how many “good men” Penney had found, trained, nourished, and (like his mentors) financed into partnerships:

1908

- Bingham, Utah — owned by Penney and Mudd

- Preston, Idaho—Penney and Neighbors

1909

- Eureka, Utah—Penney and Sams

- Malad, Idaho—Penney and Neighbors

1910

- Midvale, Utah—Penney and Mudd

- Murray, Utah—Penney

- Price, Utah—Penney and Sams

- Provo, Utah—Penney Hoag and Sams

- Rexburg, Idaho—Penney Neighbors and Woidemann

- St. Anthony, Idaho—Penney and Truex

- Bountiful, Utah—Penney and Mudd

- Ely, Nevada—Penney and Collins

1911

- Mt. Pleasant, Utah—Penney Sams and Hicks

- Lewiston, Idaho—Penney Neighbors and Brown

- Moscow, Idaho—Penney Neighbors and Coffey

- Spanish Forks, Utah—Penney Hoag and Sams

- Richfield, Utah—Penney Mudd and Malmsten

- McGill, Nevada — Penney and Collins

- Pendleton, Oregon—Penney and Frost

- Walla Walla, Washington—Penney and Hyer

Opening eight stores in 1910 and eight in 1911 was exceeded by twelve openings of 1912. But this was just the beginning. Penney and his partners dreamed of a thousand stores (achieved in 1928).

Each manager could own part of the next store, if he trained a good manager for it or for his own store so he could move on to the new one. Each store became a “mother store” to others. Managers mentored and nourished each other.

But life was not easy on J. C. Penney—in 1910, his beloved Berta contracted pneumonia and died suddenly, leaving him with two small boys, a broken man.

He almost turned to drink, but his strong faith enabled him to resist. Over time he recovered, more energized than before.

Penney continued to learn. He had never been much of a book reader, preferring practical experience, but in 1915 he discovered the book Youth and Opportunity by Dr. Thomas Tapper. He then spent a half a day each day for the next eighteen months being tutored by Tapper, who introduced him to the great literature and thinkers of the ages.

“If a man or woman has not found happiness in work, the probability is that it will never be found anywhere, for happiness lies within. Happiness is not the gift of outer circumstance.”

THE SYSTEM

Penney’s system, learned from Callahan, Johnson, and the other Golden Rule operators, required a new partnership agreement for each store, a very complex arrangement. Continued rapid expansion required an easier organizational form. It also required bigger bank lines of credit, and the banks could not understand all these partnerships. Over the next several years, the company first converted to a stock ownership system, but it was just as complicated: each store partner received a class of stock that only related to their store, and got dividends on that stock in proportion to their store’s profits. J. C. Penney owned over 50% of the total stock. (Not until 1927 did the company have stock which was the same for everyone, but this was supplemented by handing out a sixth of each store’s profits to its managers.)

The company grew so big that a “headquarters” was required—first in Salt Lake City, then in New York City—to be closer to suppliers. Central accountants and buyers were put in place. But most of the buyers and all the key executives were former store managers or had store experience.

Massive efforts were required to “find the right men” for the chain as it grew through one hundred stores. Less than 5% of applicants made the grade. J. C. Penney personally interviewed five thousand men in one year. The company was like the retail version of the Marines: tough to get in, brothers for life. Those who drank liquor or used tobacco were out. Gradually, training courses and an internal company magazine, The Dynamo, were established. Frequent national and regional conventions of managers were held, with Penney and other leaders speaking at every opportunity. Many innovative and unusual employee benefits and insurance were introduced. In both World Wars, employees who had gone to war continued to receive partial salaries from the company.

The company developed a large team of central buyers who worked hard to find the best merchandise at the lowest prices. Still, each manager decided what was carried in his store — because he knew his customers — and decided how to price each item for his market and his competition. With support from headquarters, each manager put together his own advertising—eventually in over two thousand newspapers across the West.

J. C. Penney had a somewhat unusual attitude toward competition. In the 1920s, mail-order giants Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward began to open stores across the United States, selling many of the same soft goods the Golden Rule Stores sold. But they also had the drawing power of hard goods used by farmers and suburbanites. In one location, the Golden Rule landlord was about to lease the space next door to one of these new competitors. The manager wrote headquarters pleading for them to get the landlord to deny the lease to the competitor. But Penney wrote back that he would do everything in his power to get the store next door open, as it would draw more traffic and keep the Golden Rule honest. Another manager, hearing of the new competitor, wanted to run ads showing how much better the Golden Rule was. But he was told to run an ad welcoming the competition to the community.

Managers were expected to be leaders in their communities. Over 20% of them were past or present presidents of their Chambers of Commerce.

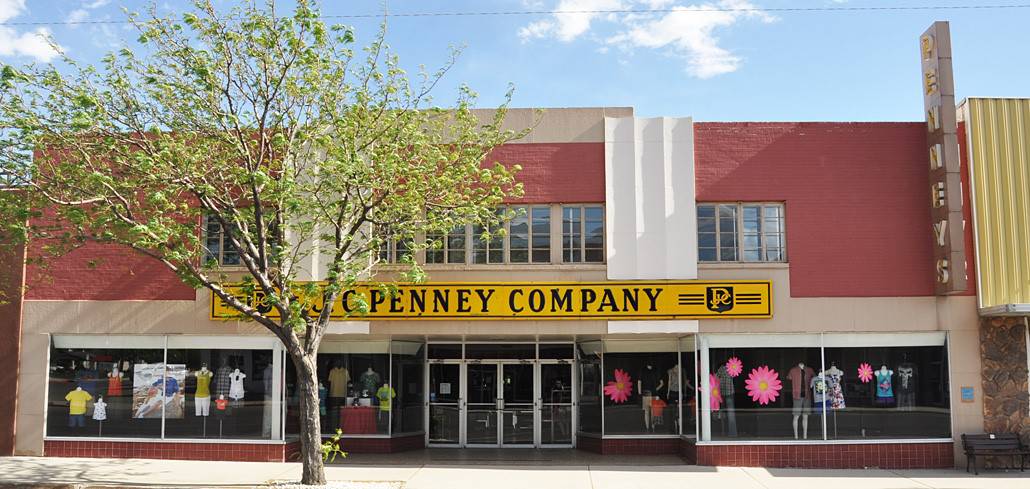

Over time, the company had begun using black letters on a yellow background to identify its stores, and often said “J. C. Penney” under “The Golden Rule.” By 1919 it was determined that all stores should go by the new common name of J. C. Penney. In the 1920s, the company acquired most of the old Golden Rule Stores, even including Tom Callahan’s mother’s store in Chillicothe, Illinois.

The company gradually entered larger cities. The Salt Lake City store was for many years the most profitable. It also began to enter Midwestern and Eastern markets. But the store base was still largely in small towns in the West, often in cities of under 10,000 population (shades of Sam Walton!).

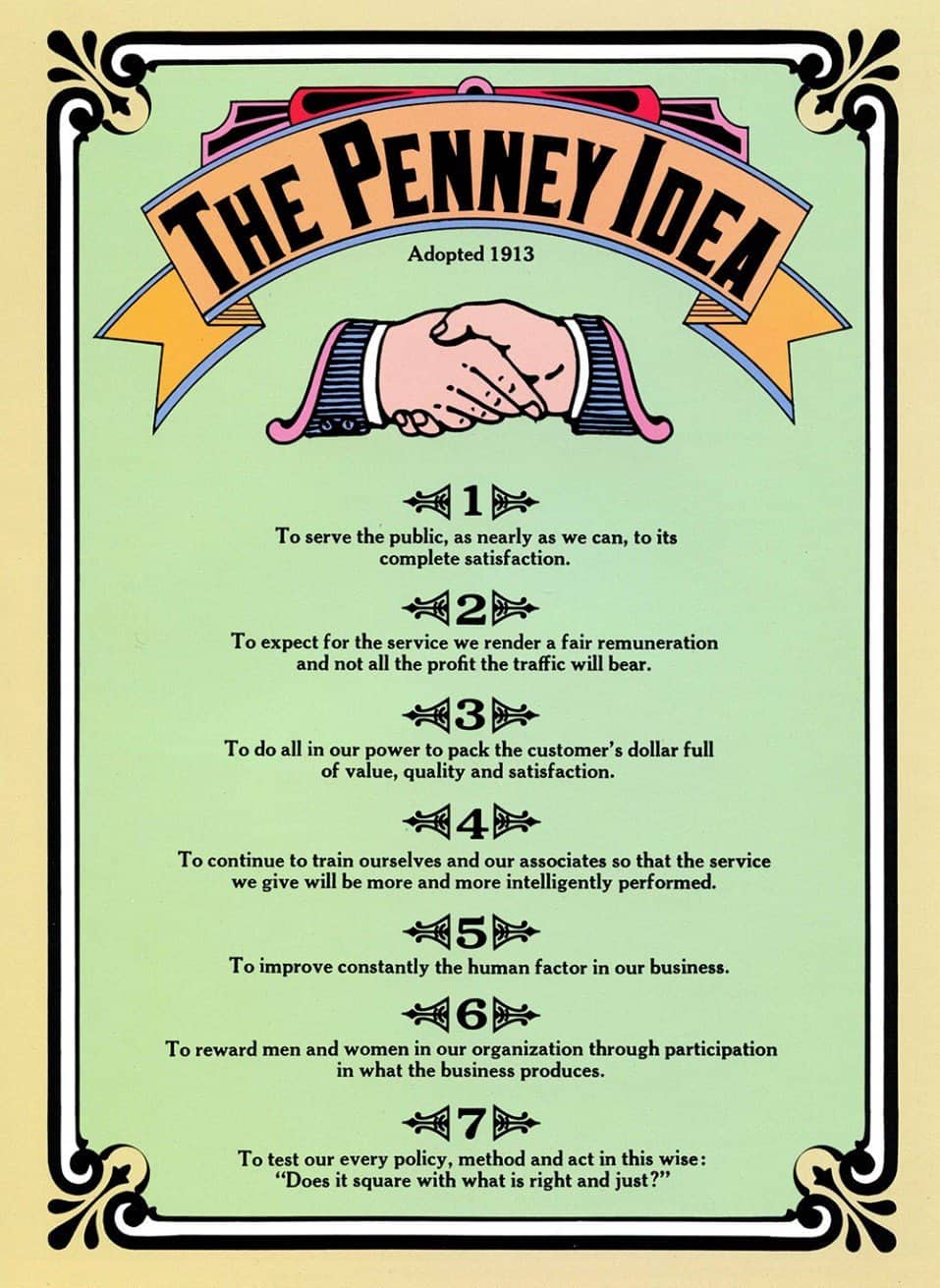

The company’s message to all associates, whether managers or clerks, was the importance of serving the public, of keeping prices low, of living by the Golden Rule. And above all else, cooperating—with headquarters, with the other Golden Rule Stores, and within their own communities. “HCSC” became the key letters: Honor, Confidence, Service, and Cooperation.

Throughout this period of rapid growth, Penney maintained the fundamental system of sharing ownership—or a big share of profits—with those who made his success possible. A 1950 article in Fortunemagazine entitled “Penney’s: King of Soft Goods” stated that no one in the company, by then the nation’s third largest non-food retailer after Sears and Ward’s, received a salary of more than $10,000. But profit sharing meant corporate executives could earn more, and store managers much more. The Seattle store manager made as much as $125,000 per year in the late 1940s—or $1.3 million in today’s dollars. It was not uncommon at that time for managers to earn $30–50,000, ten to fifteen times the average American family wage.

In 1927, Penney predicted the company might someday reach sales of a billion dollars—a goal which was achieved just twenty-four years later, in 1951.

By 1929 the J. C. Penney company was so highly regarded that both Sears and Ward’s tried to merge with it to obtain their retail and buying expertise and improve their own chains. Despite Penney opening the company’s books and sharing “everything,” and despite enthusiasm on the part of the other companies’ owners, the Penney company ultimately decided it could best preserve its unique sharing culture by remaining independent.

Another aspect of J. C. Penney himself was his ability to trust men, and to delegate. Unlike other retail chains, he never bonded his managers to insure against theft and embezzlement. When he was convinced he had the right team to continue building the company, he stepped up from president to chairman in 1917, at the age of forty-two turning the daily reins over to longtime colleague Earl Sams.

“CHOOSE A CAREER WHICH APPEALS TO YOU MOST AND AVOID THE DANGER OF BEING DIVERTED FROM THAT CAREER BY THE POSSIBILITY OF IMMEDIATELY EARNING WHAT WOULD SEEM AT THE TIME TO BE A LARGE SALARY.”

J. C. PENNEY, PHILANTHROPIST AND TEACHER

By the 1920s, J. C. Penney was worth perhaps $40 million, over $500 million today. His $3 million life insurance policy was reportedly smaller than only those of movie mogul Adolph Zukor, retail kingpin Rodman Wanamaker, and chemical and auto leader Pierre Du Pont.

He had an estate in the Hudson Valley north of New York City. He bought a mansion near Miami Beach, on Biscayne Bay, replete with the icon of wealth of the day, a pipe organ. He became enthusiastic about the future of Florida and invested heavily in real estate there.

He perpetually visited stores— where he waited on customers and worked the shelves—and spoke at managers’ conventions to inspire and encourage his partners. But he now had the time to serve in broader ways.

He underwrote Christian causes like the Christian Herald magazine. He wrote a column for the magazine, and made endless speeches across the country espousing his ideas of thrift, hard work, right living, and ethical business.

Penney’s greatest passion, outside Christianity, was his desire to help America’s farmers, whom he had long understood and empathized with. A believer in learning and experimentation, he started Penney Farms in Northern Florida, a massive 120,000-acre effort to try new experimental farming methods. He brought in “good men willing to work” from all over the United States, and funded everything. There he also founded Foremost Dairies to try more scientific methods of dairy farming. On the same property, he opened retirement apartments made available to retired preachers and missionaries free of charge. He developed one of the nation’s top herds of Guernsey dairy cattle in Florida and at Emmandine Farm in Dutchess County, New York.

J. C. Penney remained extremely active in the affairs of the company, but he and the others at “the top” were far from autocratic. They put as much power into the hands of store managers, close to the customers, as possible. The company was the ultimate decentralized enterprise. Often managers said, “God help this company if it ever falls into the hands of a mastermind.”

Penney again found love, marrying Mary Kimball in 1919. In 1920, they had a son. But again, fate befell him: she died suddenly in 1923. Penney dealt with this loss more calmly than the first time he was widowed, having come to regard his few years with her as a treasure.

In 1926, he tried marriage for the third time, this time to Caroline Autenrieth, twenty years his junior. This one lasted—for forty-five years, until Penney’s death. They added two daughters to the family.

But Penney’s misfortunes were not over.

“It takes a big man to believe in other men, to entrust his affairs to them, and having done so, to discharge anxiety from his mind.”

THE CRASH

While the Penney company fared relatively well during the Great Depression due to having no debt, only taking cash, and offering low prices, no one was immune from the effects of the stock market crash. Penney, who had borrowed against his stock and sold some to younger partners, saw the price drop from over $100 to $13. The banks called in his loans and his collateral including Florida real estate, the value of which was also devastated.

J. C. Penney had to give up on his Florida farming dreams. He sold the Miami mansion. He cut back on financing the Christian Herald. He lost control of Foremost Dairies, but retained some stock (that company went on to become the third largest dairy corporation in the world in the 1950s). Yet still, he borrowed what he could to continue funding causes he believed in.

But throughout this period, he never stopped preaching and writing, espousing his belief in human nature, in Christianity, and in his many J. C. Penney partners. Old friends and relatives loaned him money to get through this period, and the company briefly paid him a salary for the first time in many years.

THE LONG GAME

Nevertheless, the man was far from done.

Recovering substantial wealth—and buying more Penney stock in his old age—he never stopped writing, never stopped making speeches. He became a national celebrity as the company became known throughout the United States. In 1959 alone, at the age of eighty-four, he attended fifty-nine store openings, made a hundred speeches, spent two hundred days on the road travelling sixty thousand miles, and appeared on twenty-seven radio and television programs. He returned to Kemmerer each year to honor his and the company’s humble beginnings. He often visited his birthplace, Hamilton, Missouri, where he helped build the school and library. He wrote three books of reminiscences and Christian inspiration.

He left Florida and focused on New York, where he came into the Penney office every day. He met with any employee who was in the city.

He and third wife Caroline became active in the New York Metropolitan Opera. They travelled the world with their now five children of diverse ages.

Legends about him abound: that he would not hire someone who salted his food before trying it, because that meant he was pessimistic; that his executives had to leave tips when they lunched together, as he did not believe in tipping. Whenever in a store, he waited on customers.

In 1971, when James Cash Penney died at age ninety-five, the annual sales of the J. C. Penney company were $16 billion, second only among non-food retailers to then giant Sears, Roebuck.

“It is easy to copy someone else. By the same token it takes courage and fortitude to be different. The ways you are just like other men never get you anywhere. You must make your way on the difference. It is your cornerstone. You can build on nothing else.”

EPILOGUE

During the 1960s and 1970s, the J. C. Penney company went through massive changes. Against his vote, but as always with his support of the final decision of his partners, the company began to offer credit. He feared it would cause customers to buy things they didn’t need. The company for several years departed from its soft goods roots by adding hard goods, appliances, and auto centers. It shifted from its small-town Western base into a major national retailer as an anchor in malls from coast to coast. It diversified broadly— into drug stores, discount stores, a mail-order catalog, and European retailing. It took on large amounts of debt.

Over time, the company then returned somewhat to its roots, focusing on soft goods and divesting its many acquisitions.

Fast forward to 2011. Under pressure from major Wall Street investor William Ackman, the company appointed former Target executive and Apple Store leader Ron Johnson as CEO. Johnson decided to remake the company into a new form of department store. But he did not test his ideas in any region or store first. Virtually overnight, the company dropped the frequent price promotions of prior leadership. It didn’t work. Company sales dropped precipitously, down about 30%, and profits became huge losses. In 2013, Johnson, perhaps the “mastermind” that so many feared, was fired and Ackman left the board of directors. The company was a wreck, on the verge of death.

After bringing back Myron Ullman, whom the board had fired when they brought in Johnson, the ship began to right itself. Today under former Home Depot executive Marvin Ellison, the J. C. Penney Company is making some progress, but the road has been hard. (Ellison is one of only three African-American Chief Executive Officers of a Fortune 500 company as of this writing.) With many observers not believing in the future of the company, the stock in recent months hit an all-time low of under $3 per share, valuing the company at less than one billion dollars. Contributing to this decline is the general cloud over bricks-and-mortar retailing as Amazon and other online sellers become larger and larger.

Yet Penney’s has made many major improvements in its stores, including adding highly successful Sephora cosmetics departments. Analysts observe that employee morale, which would have meant everything to J. C. Penney himself, is much improved. Former industry leaders Montgomery Ward and F. W. Woolworth are long gone. Sears, Roebuck is in even rougher shape than Penney’s, with sales declining rapidly. Perhaps, when all the dust settles, J. C. Penney the company will go on to another 115 years of life. It has been a monument to one of the great merchants of American history, and may continue to be so.

SOURCES

This article was based in large part on Creating An American Institution: The Merchandising Genius of J. C. Penney, by Mary Elizabeth Curry. The basic biography of Penney is Main Street Merchant: The Story of the J. C. Penney Company, by Norman Beasley. Penney also wrote his own story in Fifty Years with the Golden Rule: A Spiritual Autobiography and View from the Ninth Decade: Jottings from a Merchant’s Daybook. Most of the quotes in the article come from a compilation of his writings entitled Lines of A Layman: The Golden Rule in Everyday Living. Other books about him include J. C. Penney: The Man with a Thousand Partners, by Penney as told to Robert Bruere; The Spiritual Journey of J. C. Penney, by Orlando Tibbetts, and the more recent J. C. Penney: The Man, The Store, and American Agriculture, by David Kruger. Fortune magazine ran full stories on the company in the September 1950, July 1967, and March 1, 2016 issues.