This article was originally published on washingtonexaminer.com

There are a lot of issues that divide friends and neighbors in the United States. Occupational licensing reform should not be one of them.

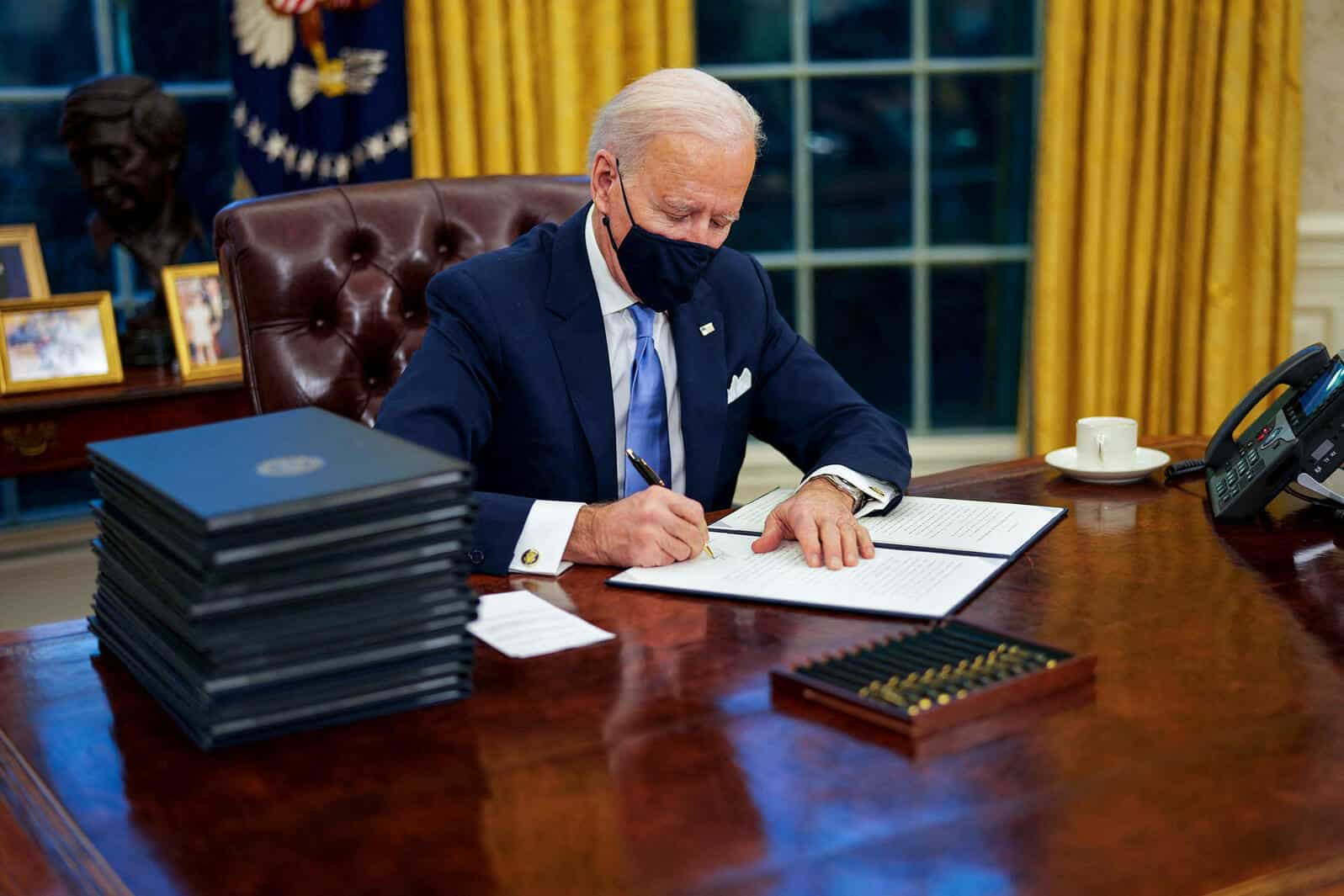

President Joe Biden’s recent executive order is a case in point. The order calls upon the Federal Trade Commission to issue new rules that eliminate occupational licensing restrictions that “unfairly limit worker mobility.” The Biden administration is only the latest to acknowledge the costs associated with occupational licensing. Both the previous Trump and Obama administrations took similar actions.

Occupational licensing laws are passed with good intentions by policymakers: trying to set minimum quality standards for professional services. But licensing has clearly spread over the years to professions where it is very hard to justify. Barbers and hair braiders are clear examples; there are better ways of regulating the market without onerous licensing.

It simply doesn’t make sense for state bureaucrats to decide what constitutes a good haircut.

Although the FTC has played an important role in shedding light on the anticompetitive effects of occupational licensing, even bringing a critical case against the North Carolina dental board to the Supreme Court , the onus for occupational licensing reform will largely continue to fall upon individual states. At the very least, the FTC can provide best practices to states, and it won’t have to reinvent the wheel.

A number of states have emerged as leaders in reform and can serve as a template for other states looking to act on the Biden administration’s calls for reform.

Arizona was the first state to recognize other state’s licenses unilaterally with a historic reform in 2019. Since then, Iowa , Kansas , Mississippi , and Missouri have passed similar reforms — in some ways improving upon Arizona’s reform by allowing unlicensed workers to begin working in licensed professions if they can demonstrate sufficient experience.

Economic research has shown that overly restrictive occupational licensing can reduce geographic mobility by as much as 7%.

If workers can demonstrate competency in a profession in one state, it also doesn’t make sense to force them to jump through arbitrary hoops.

This includes half-measures that several states have passed that allow licensing boards to deny licenses to workers lacking “substantially equivalent” standards. South Dakota was a recent state, along with my home state of Pennsylvania , to pass this much weaker reform.

In addition to this type of reform, it is important for states to reconsider if occupational licensing is the appropriate regulatory tool. As an example, Florida last year removed occupational licensing for a number of occupations, including interior design.

In general, the momentum for licensing reform has increased in recent years. From 1973 to 2012, my own research indicates that eight occupations were successfully delicensed. From 2015 to 2020, that number has been multiplied fourfold with 35 occupations successfully delicensed.

The market has evolved and changed since many of these licensing laws were written. Consumers have access to information about provider reputation at their fingertips with robust online reviews. And research has indicated that consumers care more about online reputation than licensing status when choosing home repair contractors.

Biden’s recent executive order is the latest indication that licensing reform should enjoy broad bipartisan support. The ball is now in the court of state lawmakers to heed the call and move forward with licensing reform that can make a real difference in people’s lives.

Edward Timmons is a senior research fellow with the Archbridge Institute and the director of the Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation .