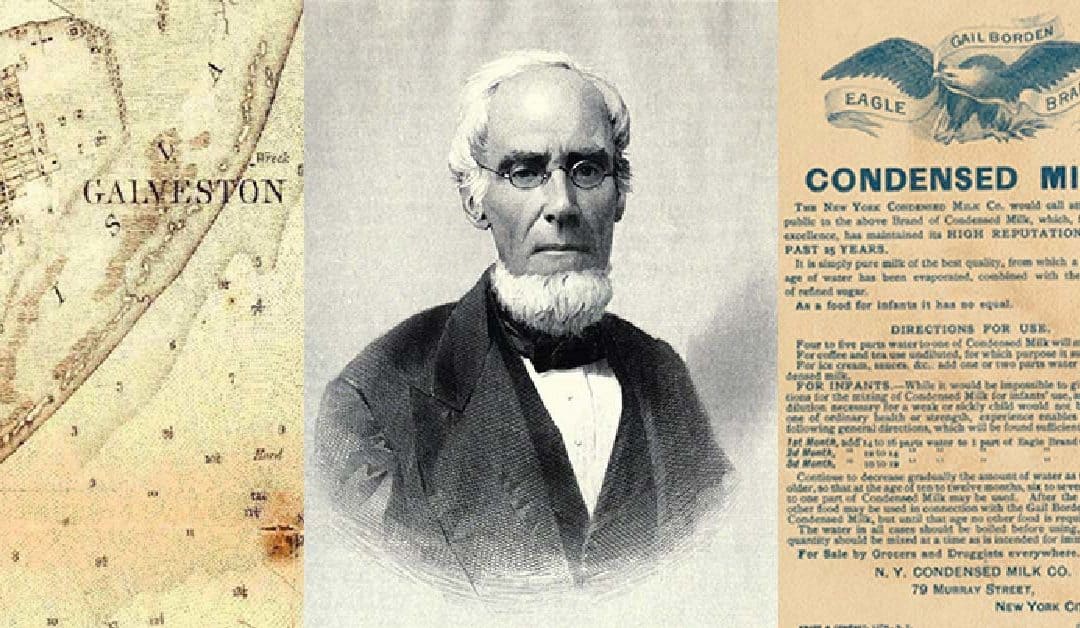

Born in upstate New York in 1801, Gail Borden was raised there and in Kentucky and Indiana. As a young man, he moved to Mississippi and then Texas in search of the land of greatest opportunity. He arrived in Mexican Texas just as Stephen F. Austin was developing a colony of “Anglo-Americans” there. Borden played a key role in the Texas struggle for independence from Mexico, helping to lead the new nation. He was one of the first newspaper publishers in Texas and laid out the cities of Houston and Galveston. Above all else, Borden was a tinkerer and dreamer. His continuous flow of inventions met with failure after failure as he exhausted his financial resources. Never giving up, in his later years he changed the American dairy industry, developing the first successful condensed canned milk. The Borden brand continues on dairy products to this day. This is his story.

Beginnings

Gail Borden Jr. was born the first son of Gail Sr. and Philadelphia Borden on November 9, 1801, in the Chenango Valley of New York. Gail Sr. was a reasonably prosperous farmer and sawmill operator in the growing community, but life amongst the Oneida Indians was primitive—dirt floors and log cabins. Gail Jr. was soon enough followed by three younger brothers and a sister.

Young Gail learned the required skills of hunting, fishing, and woodcrafting well. When the boy was twelve years old, his father sold his 115 acres for $1,620 and decided to head west like so many others. After an arduous journey across land to the Ohio River near Pittsburgh, the family finally settled in Kentucky, across the river from booming Cincinnati, the second largest city of “the West” after New Orleans. Gail helped his father and other men survey and lay out a new town named Covington.

Yet the elder Gail Borden could not resist the appeal of even better opportunities, in 1816 moving the family another hundred miles west to New London, Indiana, near the county seat of Madison. His son Gail received little formal schooling—perhaps a year and a half at most—but learned the basics of the “three R’s.” The fourteen-year-old helped his father build their new home, filling the cracks between the logs with mud to keep the wind out. Wolves were such a menace that the county paid a bounty of one dollar for each one killed, in one day paying out $58. Bringing home a “squirrel ham” was cause for celebration. Gail Jr., an excellent shot, became a captain in the local militia.

The family watched the growing traffic on the Ohio River, with boats floating downriver toward Memphis and New Orleans, and keelboat men struggling upriver against the current with their long poles in the mud. Soon practical steamboats came along, reducing the round trip to New Orleans from one year to forty-one days. The downriver trip dropped from three months to two weeks, freight rates were lowered by 60 percent, and passenger fares declined from $150 to $25. The lure of the river grew stronger. It appears likely that young Gail made at least one round trip to New Orleans.

Those living in the Ohio Valley often developed “valley throat,” a cough attributed to the river bottoms. Gail the son developed this malady, which worsened as he grew into a tall, skinny man. It was recommended that he move away from the area. In 1821, the nineteen-year-old Gail and his brother Tom, eighteen, headed downriver toward New Orleans. By mid-1822, Gail had selected Amite County in southwestern Mississippi as the best place to settle. Brother Tom had departed for the lure of the Mexican province of Texas, along with the first Anglo settlers there.

With no money to invest in farmland, Gail began teaching school, despite his lack of schooling himself. His health improved. Gail became known for running to and from the school. He started class as soon as the sun came up. He was well liked and he liked people. Borden began developing a lifelong reputation as a fast and frequent talker. In 1826, at the age of twenty-four, he was named county surveyor. In this role, he learned every nook and cranny of the county.

In Amite County, Gail got to know the fourteen-year old Penelope Mercer, daughter of the locally prominent Eli Mercer. On March 18, 1828, twenty-six-year-old Gail married sixteen-year-old Penelope.

On to Texas

Meanwhile, in 1824, brother Tom had arrived in Texas, then part of Mexico, and had become one of the first “old three hundred” settlers in Stephen F. Austin’s colony of immigrants from the United States. Texas had plenty of land, bestowed upon the settlers by the Spanish (then, upon independence, Mexican) government. The growing season was long and the opportunities seemed unlimited. Gail Sr. succumbed to the lure, moving to Texas, soon followed by Gail Jr.’s in-laws, the Mercers. The journey was tough, Gail Borden Jr.’s mother, Philadelphia, died en route.

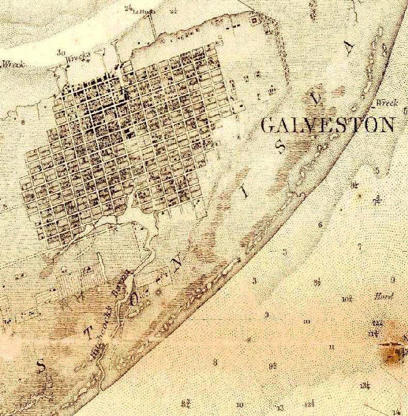

Abandoning Mississippi, Gail Jr. and his wife, Penelope, landed on barren Galveston Island, former haunt of the pirate Lafitte, on December 24, 1829. By February of 1830, their first child, Henry, was born, to be followed by six other children.

Texas was wide open. Less than two thousand Anglo-Americans inhabited a land as big as France. Gail Jr. was granted 4,428 acres of land. While raising cattle near Austin’s settlement at San Felipe on the Brazos River, Gail again began surveying, learning the lay of the land and getting to know all the settlers. According to some reports, he prepared the first printed map of the new “American” Texas.

At first, life was good under the Mexican government. The capital was far away in Mexico City. The country’s leaders were occupied with their own political turmoil; Texas was a distant and unimportant province. The Bordens, Mercers, and others swore their allegiance to Mexico. But over time, the Mexican government began to meddle. A law required all immigrants from the United States to become Roman Catholics, but it was not enforced. In 1830, the government passed a law banning further immigration from the United States, which was unenforceable and only resulted in more immigrants arriving.

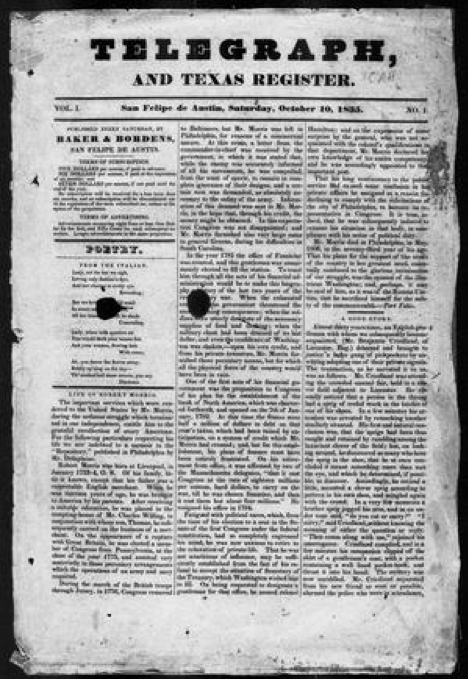

Austin and his “Texians” put up with these annoyances until General Santa Anna decided to impose military rule on the settlers. The colonists began to talk of independence for Texas. Gail Borden acquired a printing press and established the tenth newspaper in Texas, The Telegraph and Texas Register, at San Felipe. None of the other papers had lasted more than two years, but Borden’s paper was destined to become the voice of the revolution and continue on for more than forty years (though Borden sold his interest after independence was achieved). Gail, still in his early thirties, became one of Austin’s most trusted associates, keeper of the land records, and an important figure among the colonists.

Many books have been written on the story of Texas’s founding; we won’t repeat those stories here. Texans to this day “remember the Alamo,” the battle in which many of Borden’s friends died. Gail Borden was at the heart of all the action, working hard to finance his newspaper (and find paper and ink for it). The paper was viewed as essential to the war effort, disseminating news of victories and defeats. The Mexican Army advanced on San Felipe, causing the settlers to flee. The town was burned to the ground and Borden’s printing press was dumped into the Brazos River. Again and again, Austin, Borden, Borden’s newspaper, and the other settlers moved from place to place. Ultimately Sam Houston, commanding the Texas forces, routed the Mexicans at the battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836.

Texas was now a new nation. Borden served on key committees developing new laws. After acquiring a new printing press, Borden’s The Telegraph and Texas Register kept the dispersed Texians informed.

Galveston Civic Leader

Gail Borden laid out a new town for speculative developers, the Allen brothers. It was named Houston after the national hero of Texas. In 1837, President Sam Houston appointed his friend Gail Borden as customs collector at the most important point of entry, Galveston Island. Galveston had few residents (only two families) and fewer buildings. Borden immediately set out to build a customshouse there, and assiduously pursued smugglers and insured as much revenue for the new nation as he could. By 1837, Galveston’s population had mushroomed to 1,500. In 1836, Galveston had received one ship per month. By 1838, that figure was as high as five per day. Customs income collected in Galveston, over $100,000 in 1838, provided almost one-third of the nation’s finances. Borden later lost this job when his friend Houston was succeeded by Mirabeau Lamar but got the job back when Houston was again elected. Borden was renowned for his fair dealing, straight talk, and honesty.

Borden soon also became the agent and manager of the Galveston City Company which owned most of the city, selling lots to the increasing number of new arrivals as the city boomed to become the largest city in Texas. Borden served in this role for twelve years. He laid out the town, he knew every inch, and he knew everyone there.

Even these duties were not enough for the tireless Gail Borden. He saw the need for a beach house for swimmers and had one built. He worked to secure the harbor from storms and enemies. If he saw weakness in Texas’s defensive forces, he acted, whether it was within his purview or not. Borden drilled and drilled until he found an ample supply of fresh drinking water for the city. He played a key role in building and leading the Texas Baptist community, which resulted in the creation of Baylor University. He led the temperance movement.

Gail Borden was also a man full of ideas. Everyone liked him, but he was considered a “visionary” by most—at that time, a term of ridicule for an unrealistic dreamer. Borden built a home for his family and continually tinkered with everything from canning fruits to developing a wagon that could cross both land and water. He built a table with a revolving lazy susan in the center, so that food could be passed around more quickly. With no formal training, all his inventions were the result of trial and error—endless trial and error. Most everything he tried failed but was soon replaced by another idea. Gail talked and waved his hands continually. He talked fast and ate faster, claiming it never took him more than fifteen minutes to eat a meal, beating the twenty minutes of which Napoleon was so proud. Throughout his life, Gail Borden worked day and night, and rarely slept more than six hours a day. He never paid attention to how he dressed. “Quirky” was the word most often applied to him.

Gail Borden continued to own land around Texas, although indications are that he was land-rich but cash-poor for most of his life. He was continually in debt to his relatives and anyone else who would loan him money.

In 1844, his beloved wife, Penelope, died of yellow fever, like so many other Galvestonians. She was thirty-two years old and had borne seven children, of whom five still lived. Life was not easy, even in the prosperous city of Galveston.

Condense Everything!

By 1845, Gail Borden was free of most of his civic duties and a prosperous citizen of Galveston. With land later estimated to be worth $100,000 ($2.7 million today), he was the second-largest landowner in the city. With five children, he quickly remarried but little is known of his second wife, who appears to have died within ten years.

Borden was now free to focus on inventing.

A visitor who met Borden described him as follows:

Quite a tall man, very shabbily dressed, with a singularly narrow but high forehead. He had an unusually long nose. I never saw a person drive along at such a swift pace, his head bent forward, his eyes on the ground. He caught sight of me passing, but was under such headway, that he was a rod beyond me before he could turn and come back. Then he was in an extreme hurry. I could not keep up with him in what he said, at all. He shook me by the hand very cordially indeed, welcomed me and asked me a dozen questions without giving me time to answer one. Who is he? For he forgot to tell me his name.

By 1849, the aging (for his era) Gail Borden began to fixate on condensing food. Explorers ventured on arduous trips in their efforts to discover new lands. Miners rushed to California in search of gold. Soldiers and sailors traveled for months away from home, livestock, and foodstuffs. If only they could carry compact meals that did not rot!

Hours and hours of experiments led him to develop the “meat biscuit”—beef boiled down to its nutritive components and mixed with flour. The product was unaffected by months of storage and could be eaten raw or made into soups and other dishes. Gall showed others how to cook it, though often they “got it wrong.”

Gail turned his full energies to the meat biscuit. He knew this invention would change the world, making him rich and famous. Building the production contraptions himself, he borrowed against his land and borrowed again. He found partners, raised more money, and got a patent in 1850. Initial response from the US Army was positive, with Brevet Colonel Sumner of the First Dragoons, Fort Leavenworth, writing to the War Department, “I have lived on it entirely, for several consecutive days, and felt no want of any other food.” Borden built two buildings in Galveston to make this product that he was confident the world awaited. He filled the factory with machines of his own design, continually tinkering with and improving them.

But orders were slow to come in. Gail borrowed at least $5,000 by early 1851 ($152,000 in today’s money). Buried under debt, he wrote that his “head became light” and at times he “felt dizzy and almost staggered.” Shortly thereafter he wrote, “I am entirely out of money . . . if my creditors should take a panic, and begin to press, my whole property would tumble like a row of bricks.” Yet he pressed on.

Later in 1851, he raised enough money to attend a world’s fair, the Great Council Exhibition in London, where he hoped to sell meat biscuits to the British, French, and Russian militaries. Despite winning gold medals for his innovative product, orders remained slow.

Gail spent two years in New York, meeting every ship that landed, trying to sell them meat biscuits. He put in fifteen-hour days and continued to improve his machinery and production processes.

Then, in the summer of 1851, the army issued a formal report: the product was “not only unpalatable, but fails to appease the craving of hunger—producing head-ache, nausea, and great muscular depression.” Gail’s hopes were dashed, and perhaps his fortune as well.

Yet the stubborn man still believed in the power of condensation. He tried condensing tea, coffee, and many other food products. Borden said, “I mean to put a potato into a pill-box, a pumpkin into a tablespoon, the biggest sort of watermelon into a saucer.”

His favorite saying was, “I never drop an idea except for a better one.” Though he continued to promote meat biscuits through 1853, by the end of 1851 he had begun work on the next “better one”: condensed milk.

Milkman

Stories abound about exactly how Gail Borden came upon a vacuum process for condensing milk. At the time, dairies were often dirty, delivery systems were dirty, and milk was often tainted and never lasted long on the shelf. Gail realized that shelf-stable condensed milk—one quart made five or more quarts of milk by adding water—might be even more important to the world than meat biscuits.

In 1853, he applied for a patent, but it took three years to convince the government that his process was sufficiently innovative and different from prior attempts to condense milk. With no funds, he told a maker of water-wheels, “I have spent all my money and my friends will not lend me any.” He offered to pay for a machine “later.” The manufacturer agreed to the deal, as Borden’s honest demeanor led the man to state, “Mr. Borden was a man who carried his letter of credit in his face.”

Gail spent part of 1854 back in Texas selling land to pay debts and vowed to “conquer or die.” Condensed milk raised his spirits, which he said, “are yet unbroken.”

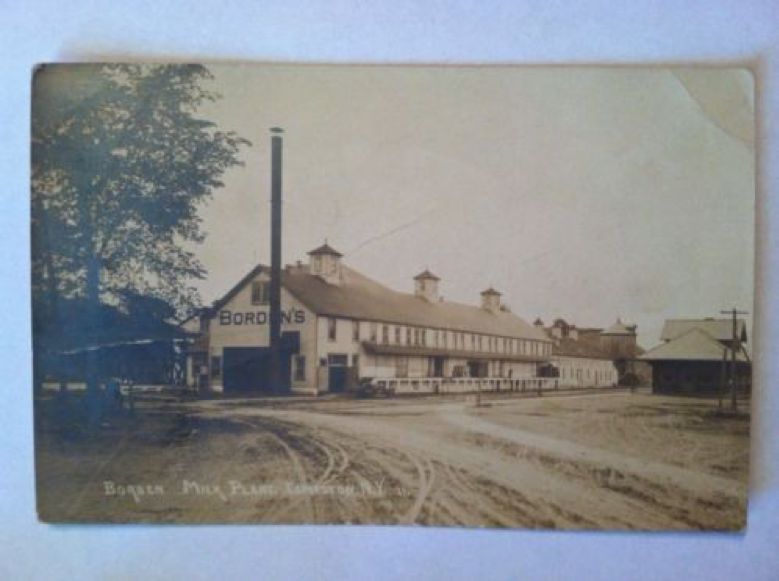

This time, unlike the inventions of the first fifty years of his life, condensed milk began to catch on. The editor of Scientific American magazine became an enthusiast and gave the product good press. By 1856, his vacuum process had also earned a patent in England. In 1855 and 1856, Gail took on new investors. He built a new factory in Connecticut, later moving it to New York State, four hours by train from the key market of New York City, where he established a sales office. Gail Borden was busier and more intense than ever in his life.

A financial panic hit the banks in 1857. The economy slowed dramatically. But Borden had to press on. Riding on a train that year, Gail sat next to Jeremiah Milbank, a prosperous New York wholesale grocer, seventeen years younger than Borden. Gail’s brain—and tongue—were racing with enthusiasm. His biographer described him as, “Fifty-six years old and looking older . . . patched clothes that did not fit. Sunken temples, greyhound nose, thin, underfed body, terribly stooped. The trenchant eye of a kindly fanatic.” But somehow young Milbank saw opportunity in the honest face of the older man, took a big gamble, and became half-owner of Gail’s enterprise, soon named the New York Condensed Milk Company.

In 1860, Borden married for the third time, to Emeline Church. This marriage lasted until his death.

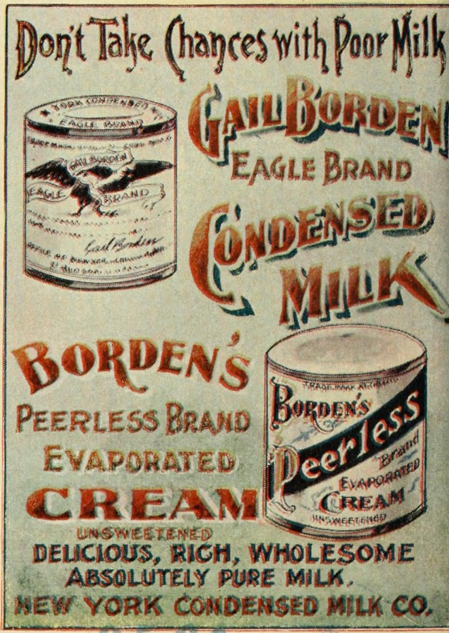

Jeremiah Milbank’s gamble was well-timed. The Civil War brought tremendous orders for the condensed milk, which was pure, durable, and affordable. The company began to advertise in major publications. More sales offices were opened and more factories were built, yet still production could not keep up with demand. By mid-1863, production was up to fourteen thousand quarts per day.

Gail Borden never stopped making improvements in the process. He instituted strict cleanliness rules for the many dairy farmers who provided the raw milk his factories used. He raised more money from Milbank.

(Jeremiah’s total investment in the company of under $100,000 became worth an estimated $8 million by the time he died in 1884, $226 million in today’s money.)

Gail Borden grew wealthy but no less quirky. He urged his factory workers to attend church on Sundays, paying them their regular hourly rate during church services. When Gail saw workers leaving on vacation, he would hand them a roll of bills, apologizing for “not having more.” He regularly showed up for work at 4 a.m. and continued throughout the day. He continued to seek other products to condense, including coffee and jelly.

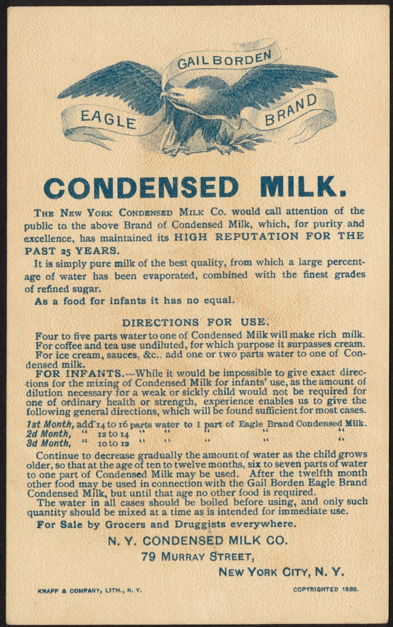

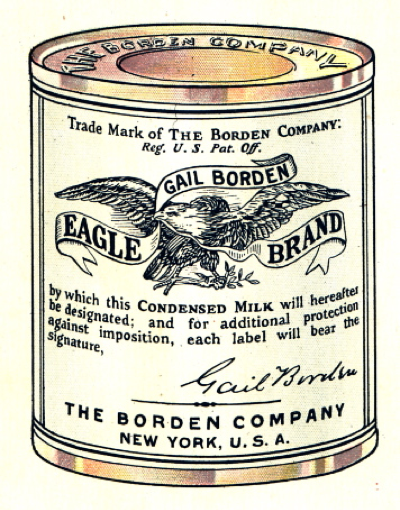

In 1866, Gail branded his condensed milk as “Eagle Brand Condensed Milk.” Eagle Brand became familiar on pantry shelves across the nation.

Now spending most of his time in the northeast, Gail’s family was spread across New York and Texas. One son fought for the Union, one for the Confederacy. Yet Gail, always committed to “doing what is right,” sided with President Lincoln and the preservation of the Union. Nevertheless, after the war, he was able to return to Texas and be well-received there. Everyone who knew the old man knew that he was an honest man of firm convictions.

Upon returning to Texas, Gail moved to the small town of Borden, where his brothers lived, west of Houston. He built mills and invested in Bastrop County. Gail Borden always saw himself as a Texan, loving the land and the people.

Gail Borden died in Borden, Texas, on January 11, 1874, at the age of seventy-two. A funeral train took his body to New York, where his epitaph read, “I tried and failed, I tried again and again, and succeeded.”

Gail Borden’s Legacy

While Eagle Brand and Gail himself were nationally known in his lifetime, the New York Condensed Milk Company was not renamed the Borden Condensed Milk Company until 1899, twenty-five years after his death. By the mid-twentieth century, the company pioneered instant coffee and non-dairy creamers. The company was best known for advertising icon Elsie the Cow and Elmer’s Glue.

The company then fell victim to rapid diversification and poor management and was ultimately broken into pieces.

Yet the brands live on today. Giant dairy cooperative DFA (Dairy Farmers of America) makes Borden cheese. Elmer’s Glue is sold by the huge Newell Brands Company. The Eagle Family Foods Group of Ohio continues to produce and sell Eagle Brand sweetened condensed milk.

Few of the great innovators we have explored in this American Originals series were as persistent over as many years as Gail Borden. Few held so many different positions, from newspaper publisher to customs collector. Even fewer played such an important role in the settling, planning, and development of an uncharted frontier. Unique, quirky, persistent—that describes the life of Gail Borden.

Source: this story is primarily based on the excellent biography Gail Borden: Dairyman to a Nation, by Joe B. Frantz (1951).